WINCHESTER, Va. — The mid-Atlantic region is blessed with multiple major and minor league baseball teams, and even independent league teams within an hour or two’s drive. But along the stretch between the Blue Ridge and Allegheny Mountains that cradles Interstate 81 as it darts southwest through the Shenandoah Valley, baseball is just starting for the summer, as it has every year for more than a century, in a league older than the American League.

Yes, really. The Valley Baseball League has undergone various transformations over the decades and teams in the area can be tracked back as far as the Staunton Baseball Club in 1866. But it first came into being as an organized league as the Valley Base-Ball League in 1897 with five charter members: Edinburg, Front Royal, Strasburg, Winchester and Woodstock. The original Washington Senators, who would relocate to Minneapolis and become the Twins in 1961, wouldn’t be founded for four more years.

The Valley League saw its most drastic renovation in 1993, when it became one of the dozen or so college wood bat leagues around America affiliated with Major League Baseball (there are more than 40 such leagues overall). If you track collegiate baseball in the area, you probably know about the Cal Ripken Collegiate Baseball League, featuring teams in D.C., Maryland and Northern Virginia. But the CRCBL was founded just in 2005 and doesn’t have nearly the history of the Valley League. For the past 25 years, the Valley League has been home to potential professional prospects looking to hone their skills and catch the eyes of scouts over the summer.

From a fan’s point of view, it’s unmistakably the same game, with many of the same comforts. Walkup music plays from the PA for each player, along with familiar songs for certain results on the field. Multiple cowbells celebrate good plays by the home side. A shaggy lion mascot roams the stands.

“A lot of people who aren’t aware of the team, once they come, they say this is a hidden gem,” said Donna Turrill, general manager and housing coordinator for the Winchester Royals. “It’s just a good, family outing, it’s inexpensive, concessions are inexpensive, and it’s just a good time.”

She’s not kidding on the concessions. For those who have grown wary of the sticker shock of major league or even minor league food prices, the sign looks like a misprint. Hot dogs run just $2, cheeseburgers $3.50. The Chick-fil-A sandwiches on sale are cheaper inside the gates at Jim Barnett Park than they are on Wisconsin Avenue in Northwest D.C.

Tickets are also just $5, $3 for seniors and just $2 for kids. With a home field that fits under 1,500 spectators, revenues are small relative to professional clubs.

The entire affair is run on a tight budget, thanks to some help from MLB and through the sponsorships sold along the outfield wall. But the Valley League has been nonprofit since 2011, relying on homestays for players. The Royals’ only full-time paid employees are their three coaches and head of concessions. Even Turrill is a volunteer.

New members of the community step up each year to help keep the team going, receiving nothing but a free season pass and gratitude in return. It’s the spirit that embodies everything that happens here.

“But we do have families that come back year after year,” Turrill said. “We’ve been housing players for seven years myself.”

***

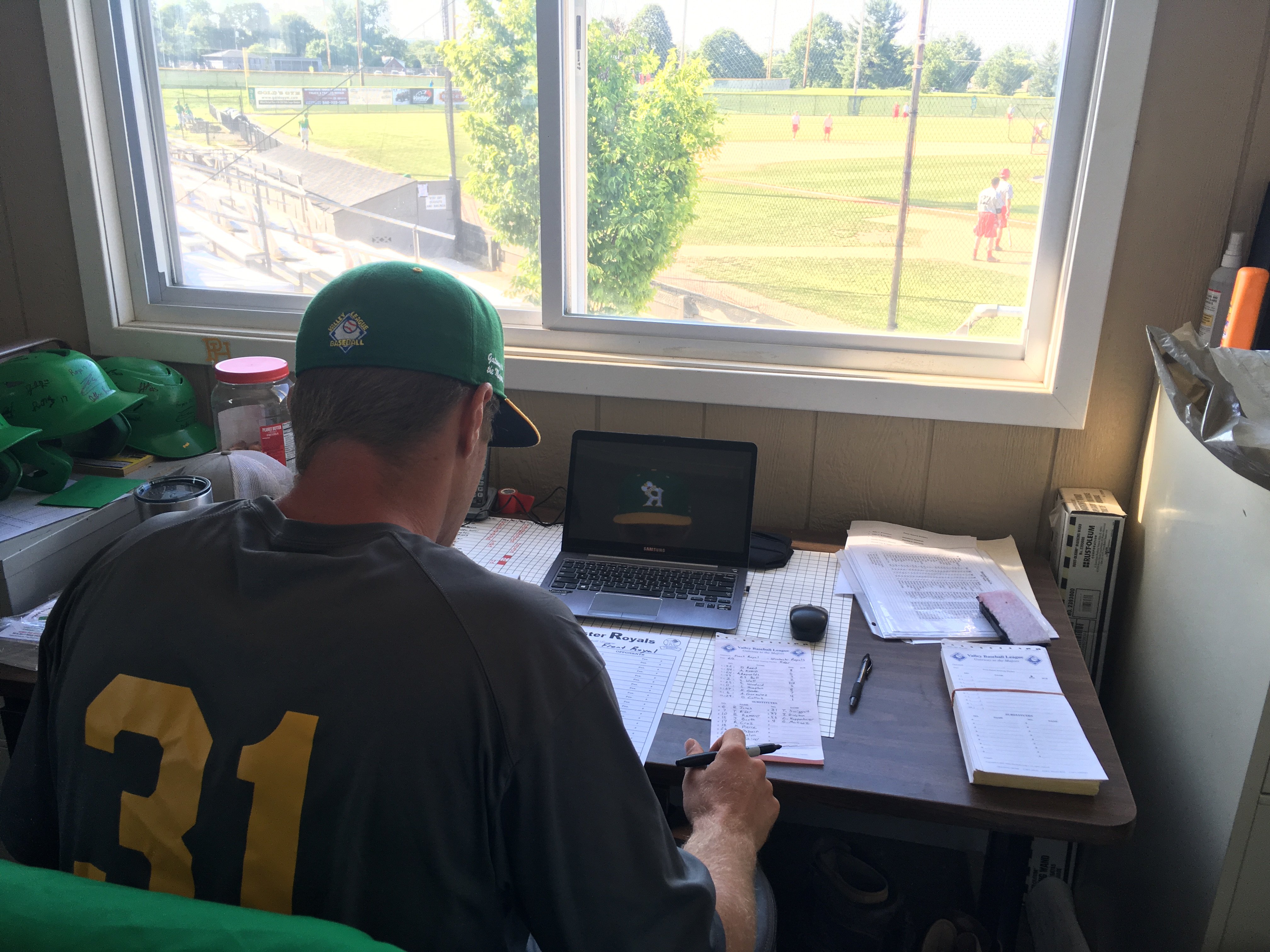

Above the field at the far end of the press box, Royals head coach Lyndon Coleman fills out his lineup card in a cozy office, half dressed, the rattle of a window-unit air conditioner humming under his excitable voice. Coleman is a Valley League alum himself, playing in the summer of 2011 before his senior year of college. Now the head coach at Pasco-Hernando State College in New Port Richey, Florida, north of the Tampa area, he’s in his third season of coaching the Royals over the summer.

There are players from Florida all over Coleman’s roster, which he is in the ongoing process of molding and shaping as the year winds toward summer. Most of the non-Floridians hail from junior colleges and universities along the Eastern Seaboard. Tyler Swiggart, a right-handed pitcher from George Washington University, is the lone local product.

“I would say the biggest thing is whoever’s recruiting the team, it depends on where their connections are at,” Coleman said. “A lot of my contacts are in the southeast region. And then, from doing this and coming up here, I’ve started to know this area of the country.”

Coleman finalizes his 29-man roster by June 6, a few days after the league opens play on June 2. That number will whittle over the summer down to 22 or 24 as players leave for summer school or sustain injuries. Last year, he lost catcher/infielder Gabriel Garcia for the best reason — he was drafted by the Milwaukee Brewers in the 14th round. Garcia signed a professional contract and was playing rookie ball in Phoenix a week later.

One name on Coleman’s roster stands out in particular: Lorenzo Hampton, an outfielder from the University of California. Rated as the 151st best player in the country out of high school when he made his college commitment, Hampton looks the part, towering over teammates. The son of the former Miami Dolphins running back of the same name, the ball pops off his bat. He’s slashing .500/.583/.833 thorough the Royals’ first five games. He’s a player Coleman has had his eye on for a few years.

“When I was down in Miami recruiting another kid off Pace High School, I saw him play a couple years ago,” Coleman said. “Then, about a month ago, I found out he didn’t have a summer team, and so I called him up to see if he was interested in coming here.”

Jim Phillips pops his head into Coleman’s office. A Valley native, Phillips has been working in one capacity or another for the Royals since 1979, long enough to see players like Jimmy Key and Reggie Sanders swing through on their way to the big leagues. He was here when Dayton Moore, now GM of the Kansas City Royals, spent four seasons coaching in the league during his days as head coach at George Mason.

“I’ve been vice president, general manager, official scorer, I even drove the bus a while,” he said. “Whatever needed to be done.”

So when Phillips talks, Coleman listens.

“Do you think there’s gonna be a lot of balls hit to center field?” Phillips asked.

There’s a pregnant pause, as Coleman furrows his brow, trying to decipher the logistics of the question he’s being asked.

“Why?” he finally responded. Phillips hands him the lineup card with a smile.

“You’ve got two center fielders.”

“Hampton’s at 9 (right field),” Coleman said, laughing as he makes the change to the card and gets ready to head downstairs.

Before we can play ball, he has to water the field.

***

Everybody pitches in to make the operation run. Players chalk the batter’s box. Swiggart, the Colonial, carries three dozen new balls in boxes from the bullpen, his tattooed arms protruding from the short, Kelly-green sleeves of his jersey for the summer.

Beyond the field itself, there are few of the facilities one associates with professional or even college ball. Notably, there’s no clubhouse attendant, because there’s no clubhouse.

A pregame snack of fruit and peanut butter and jelly sandwiches is consumed in the dugout or press box. Postgame meals are served on the picnic tables down by the bullpen.

But there is still a full team’s worth of gear that needs to be cleaned every day and prepared for the next game. So one of the players is hired to do laundry for the team for the summer.

Players hand bats off to one another, the new instrument of their game a communal weapon (the league is sponsored by Baum Bats, who provide the lumber). They hustle from the dugout to their positions and back. In between innings, they wander the concourse, splitting concessions lines, to get to the ballpark’s lone bathroom, back behind the home plate bleachers. It’s one of the more popular spots, by necessity.

“We give them practice shorts, a practice shirt and their hat, and that’s what they use for practices and pregame warm-up,” said Turrill. “Then, at 6 p.m., they get their uniforms on.”

That change happens wherever the players can manage it. A few teams have college facilities, complete with full locker rooms (Harrisonburg plays on campus at James Madison University), but that’s the exception to the rule.

The 11-team Valley League plays a 42-game season running from early June through late July, with the top eight teams advancing to playoffs for the Lineweaver Cup Championship. Teams play every day, but the top and bottom of the league is only separated by about a three-hour drive, so teams travel home from their road game destinations the same night.

“We’re not spending time and energy traveling,” said Coleman. “We’re spending time and energy getting better at baseball.”

Winchester’s longest drive is to Covington, down Highway 64, a few minutes south of the Jefferson Pools and just a few miles off the West Virginia border. Minus the hotel stays, the lifestyle gives the players a taste of what to expect in the glamour-free minor leagues — no school, lots of bus travel and baseball every day. Coleman believes the daily games and the change in bats are the biggest adjustments to make, the most telling sign of whether they are cut out for pro ball.

“They don’t have to worry about school, they don’t have to worry about studying, they get out of their house,” he said. “They are just fully immersed in a baseball experience (with) a town that really gets behind them.”

The scouts will show up as the season wears on, especially for the All-Star Game July 9 in Harrisonburg. There will also be a round robin showcase against other National Alliance of College Summer Baseball teams in Kannapolis, North Carolina, the following week. They’ll hope to duplicate the success of Atlanta Braves scout Gene Kearns, one of the Valley League’s most frequent visitors.

In 2011, Kearns saw an impressive reliever out of a small college in Indiana hitting low 90s on the radar gun with a wicked curveball. He found out the player hadn’t done much pitching at school, playing third base and had gone undrafted. Two years later, Brandon Beachy was in the rotation in Atlanta. He struck out better than a batter an inning and won 14 big league games before his career was cut short by arm injuries.

***

There are stray Nationals hats here and there in crowd, the only sign that we are anywhere close to Washington. Jim Barnett Park sits 81 miles from 1500 South Capitol St., but it might as well be 1,000. That doesn’t mean the trail from here to there hasn’t already been blazed, though.

In 2005, a second baseman out of Jacksonville University — a school that had yet to produce even an average big league player — stormed through the Valley League in his second year on the circuit playing for the Luray Wranglers, batting .347 en route to MVP honors. Eleven years later, Daniel Murphy duplicated that batting average in his first year in Washington, finishing second in the National League MVP race.

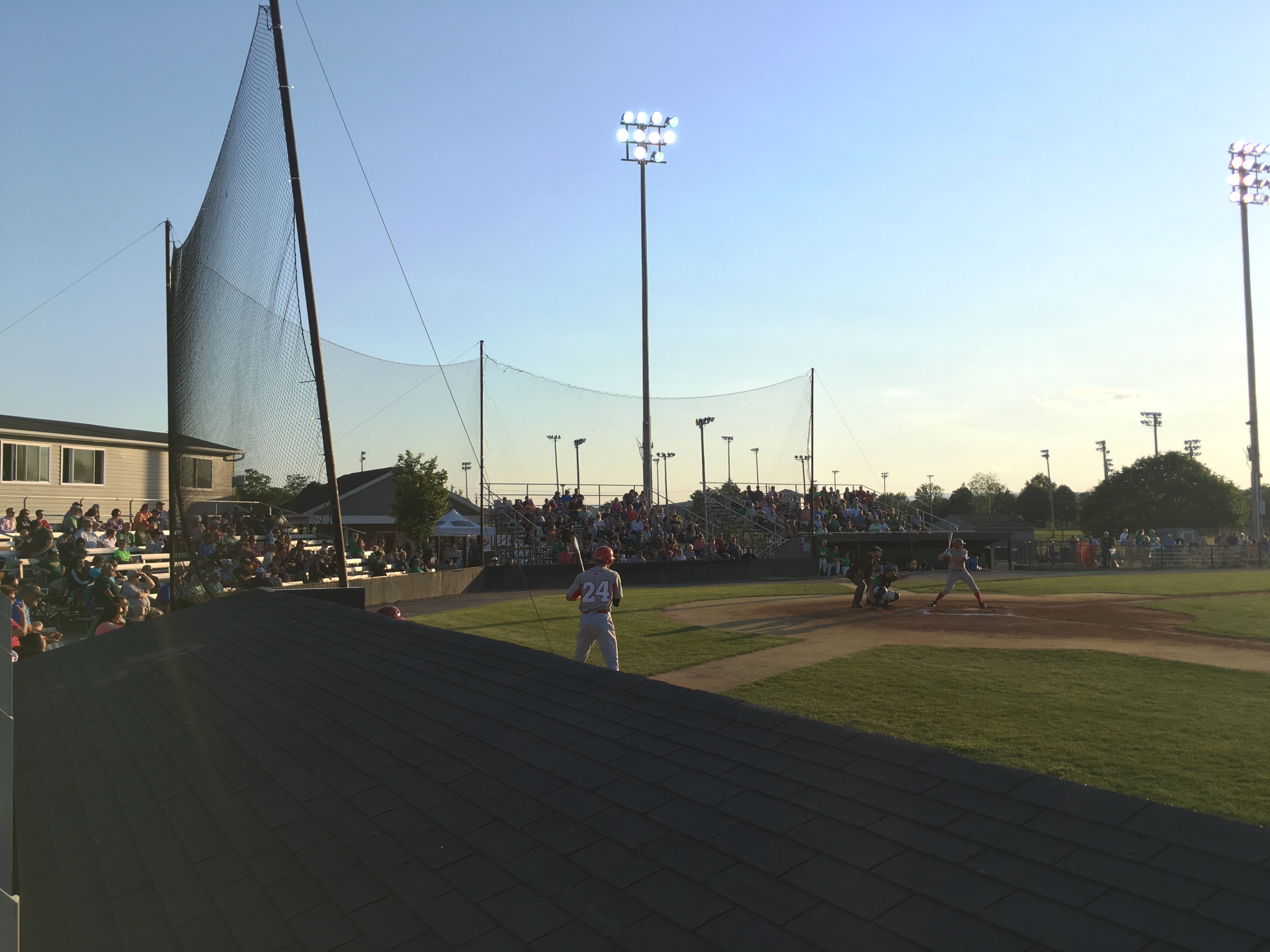

As the clock ticks toward the first pitch of the season on a picture perfect Friday summer evening, Little League games run on adjacent fields around the complex, the sounds of baseball — pings of metal bats, swells of cheering parents — floating in from all directions.

“Welcome, baseball fans …” the public address announcer calls out to the crowd still trickling through the gates and getting settled, greeted at the entrance by tonight’s celebrity guest, the Chick-fil-A cow.

“Foul balls are yours to keep tonight, thanks to Chick-fil-A,” says the voice from above.

That doesn’t mean there are any balls to waste, though. The Chick-fil-A cow itself is tonight’s ceremonial first pitch thrower, muscling an underhand heave in the general direction of home plate that reaches the catcher off a bounce. One wonders if cows even have UCLs and, if they do, how they might feel about the act of throwing a rawhide ball. But there’s no time to answer such frivolities — fresh dirt spot and all, Royals starting pitcher Daniel Collins needs that ball back. He’s got a game to pitch.

Metal bleachers stretch in five sections around the backstop and dugouts, 10 rows deep behind the plate and 15 up the baselines. A foul ball rockets back over the screen and out of the stadium toward the parking lot, making one reconsider how much of the close parking availability was a result of foresight, rather than fortune.

In the stands, the next night’s starter helps with the 50/50 raffle, selling strips of tickets measure by the length of his arm.

As usual at any game, baseball wisdom rains from the stands. With runners at the corners in the first inning, Front Royal starter Keagan McGinnis (a Haymarket, Virginia, native and Virginia Tech product) heaves a second pick-off throw to keep Alex Reynolds close at first base, soliciting the first jeer.

“Aw, leave him alone over there,” a fan barks.

“He throw it over there again, he might throw it away,” another drawls in response.

“He might.”

He does. McGinnis’s toss skips past first base and Dillon Reed scampers home from third with the first run of the 2017 season.

As the sun sets over glowing country sky to the west, the Royals win a back-and-forth affair 7-5 to open their season. It’s the start of the yearly, two-month love affair between the towns of the Valley and their neighborhood teams, steeped in the game’s history. For Turrill, it all began when she was introduced to the Royals by friends from church already involved with the club. Balancing this work with her job, she hasn’t been to bed before 1 a.m., for weeks getting everything prepared, but she wouldn’t trade it for anything.

“I absolutely love my summer sons,” she said. “I am hooked.”