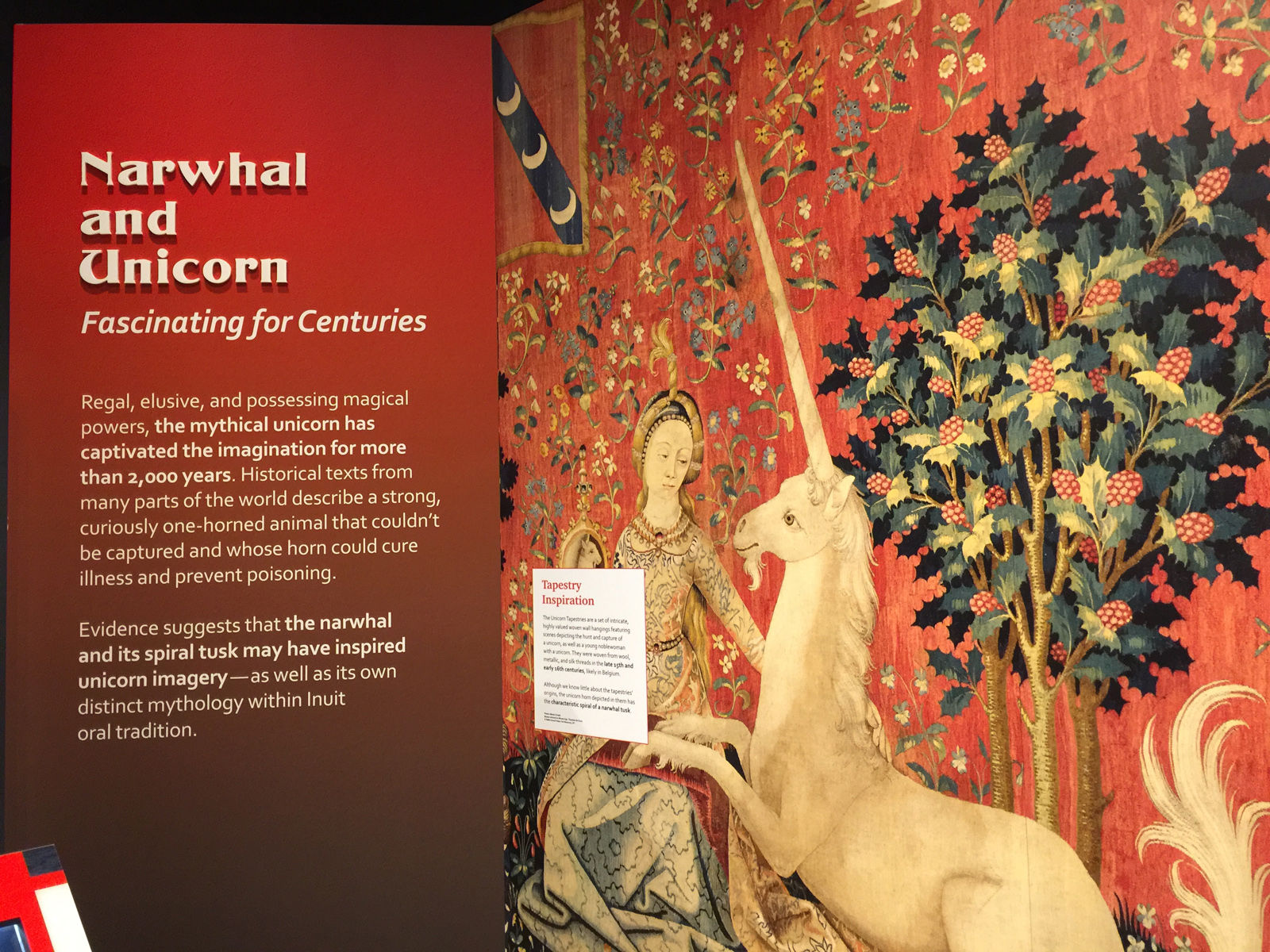

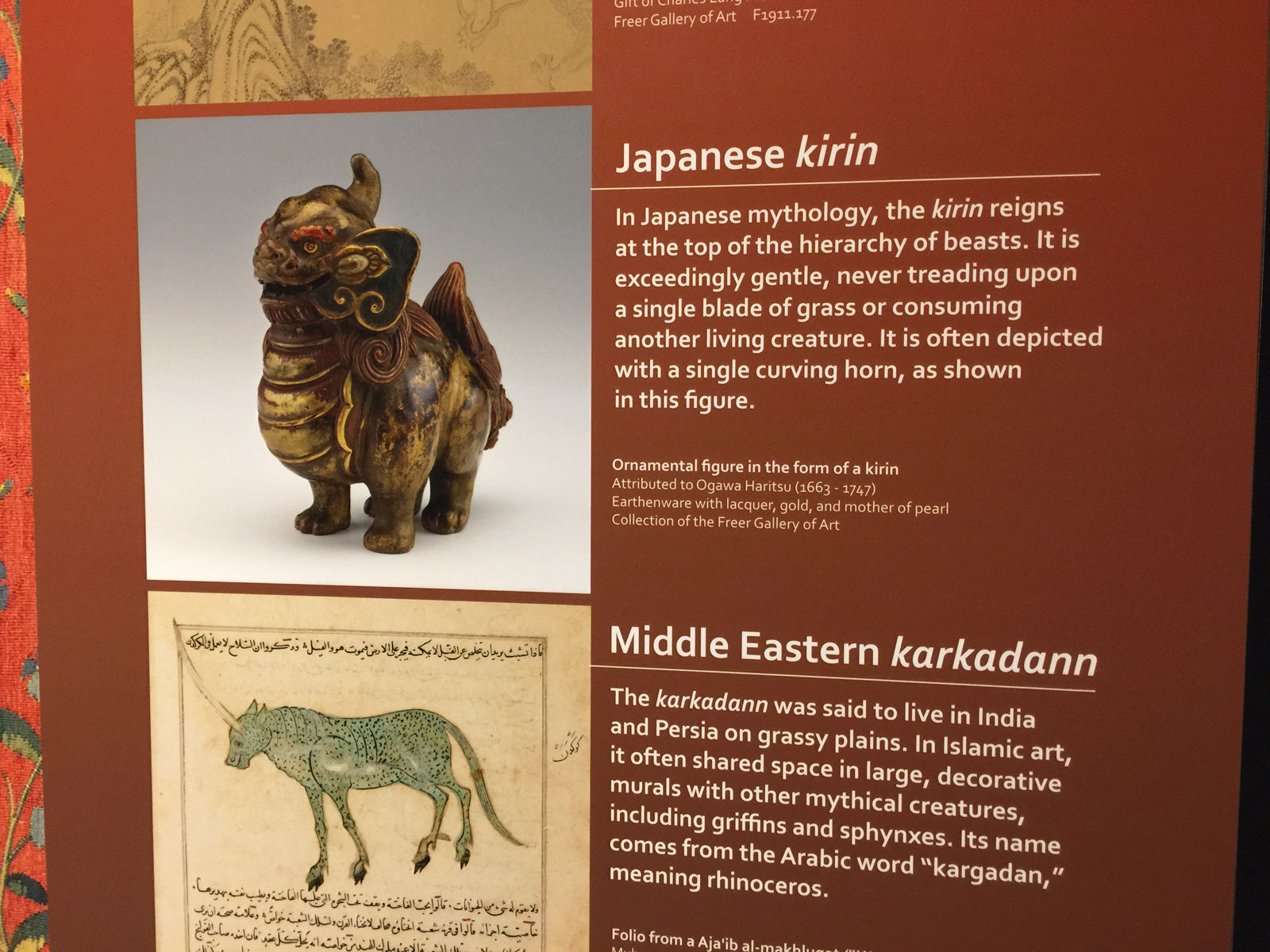

WASHINGTON — The spiral-horned narwhal is as mysterious as the unicorn legend it’s believed to have inspired.

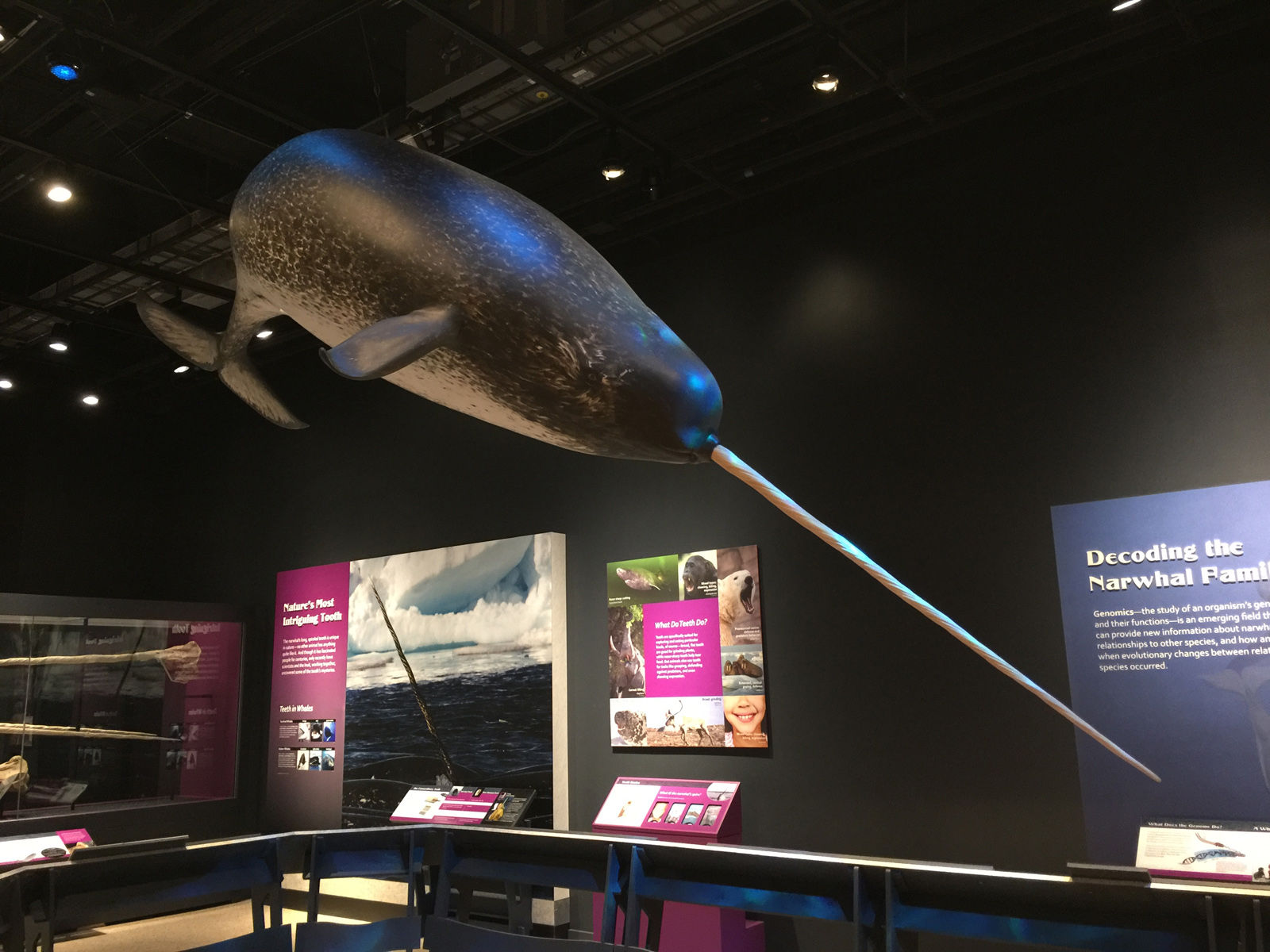

An exhibit opening on Thursday at the National Museum of Natural History displays what is known about the creature. “Narwhal: Revealing an Arctic Legend” explores the arctic, the animal and the people adapted to the animal.

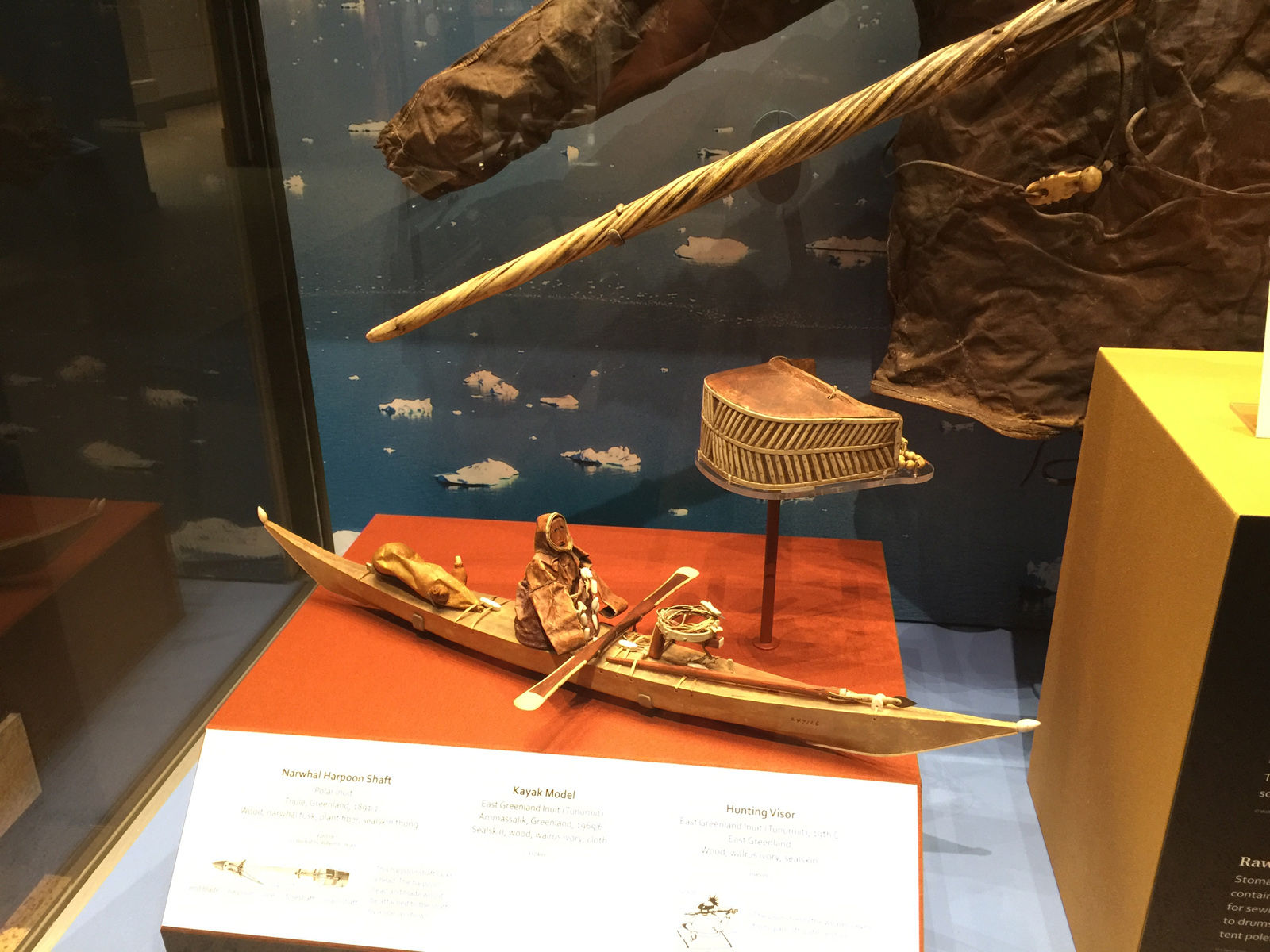

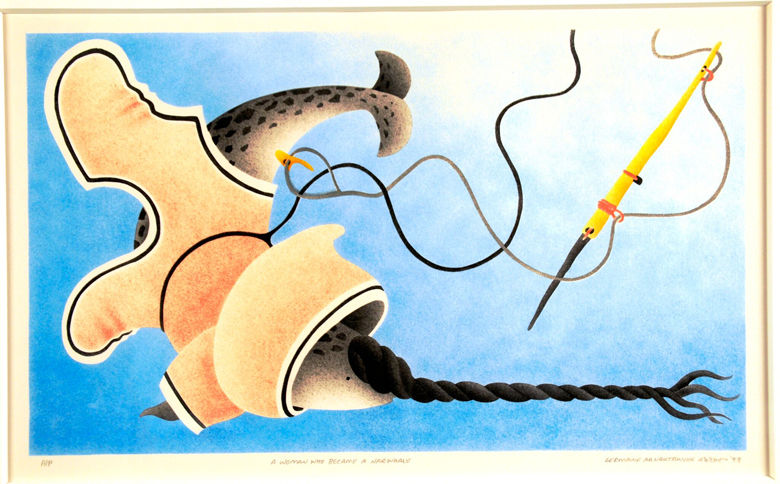

“The story of the narwhal is entwined with a culture and part of the world very few people know about,” said Bill Fitzhugh, director of the Arctic Studies Center at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History. “The Inuit need the narwhal for their sustenance, for food, for materials, for market products like carvings.”

A changing climate is allowing more access to the Arctic for researchers, tourists, shipping traffic and economic development. It’s also impacting the narwhals in two ways.

The first is that killer whales are more free to hunt narwhals in less icy waters.

The second is that there’s more “entrapment” of narwhals in inner bays that can get blocked by winter ice that gradually grows from outer bays. Eventually the ice covers the water surface and narwhals have no way to breath.

While noting those subtle changes, Fitzhugh said the narwhal population still is stable and the Inuit still are hunting them.

There are numbers of theories about the purpose of the narwhal’s prodigious tooth, but none is a leading contender.

“This is by far the most extraordinary tooth on the planet,” said Martin Nweeia, who is a dentist in addition to being a research associate in vertebrate zoology at the Museum.

Some of the theories:

- It may be used as a sensory organ.

- The tusk may be a signal to females of a male’s fertility.

- Narwhals rubbing tusks together may be a display of dominance to attract females.

Nweeia also pointed out the narwhal’s tusk is the only spiral tusk in nature and is inside out when compared to other teeth.

It also has a network of nerve connections on the outside and hard material on the inside. “This is not seen anywhere else in nature,” Nweeia said. Those nerve connections can detect levels of salt in the water that fluctuate based on how much ice is freezing or melts. The creation of ice pulls “fresh” water out of “salt” water.

The tusk is the most extreme example of asymmetrical teeth in nature, where a tooth on one side grows dramatically longer than the corresponding tooth on the other side of the mouth.

In a typical male, the right sided tooth never grows long enough to become visible. In about one in 500 cases the right sided tooth can equal that on the left.

The tusk material has an unusual degree of both strength and flexibility. Nweeia said a group is now cloning the tissue to create material that might have modern day applications.

“When you look at this whale there are so many things that don’t make sense,” Nweeia said. “It is counterintuitive to everything I learned as a dentist.”

Nweeia hopes the exhibit inspires people, especially kids, to follow their curiosity.

“Why is a country dentist in Connecticut going up to the arctic, three thousand miles due North to wade in 36 degree water to study an elusive whale with this tooth?” Nweeia asked rhetorically. “It’s because I’m a curious kid and I kept hold of that.”

And those of you curious, the whale’s name is pronounced two ways. Either NAR-Whale or NAR-wall.