WASHINGTON — Can you believe it’s been 20 years?

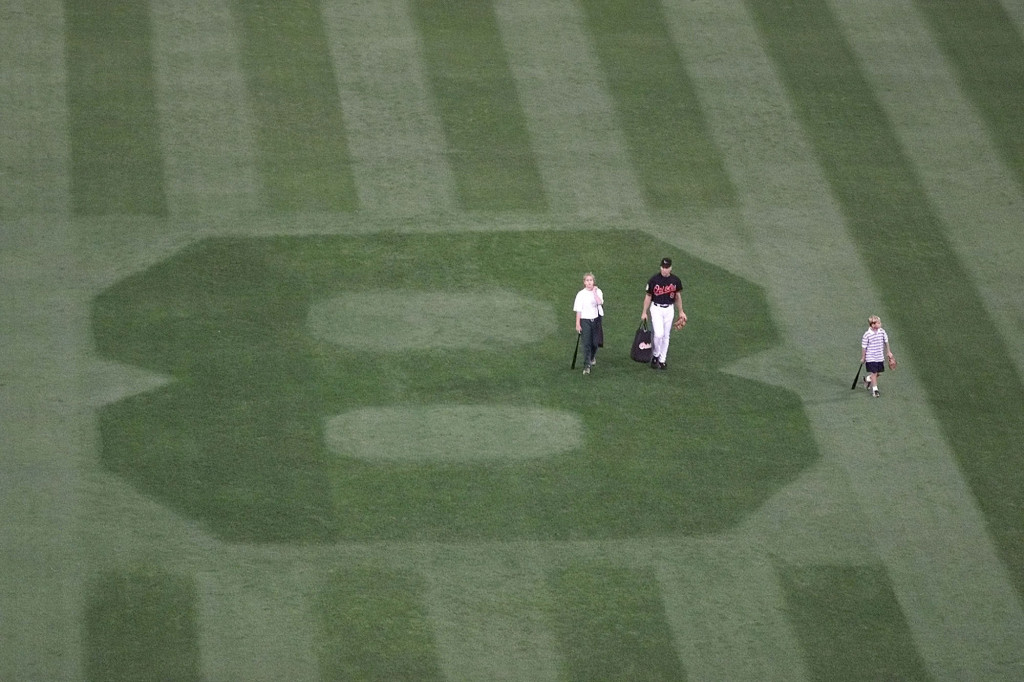

The Baltimore Orioles open their home season Friday afternoon at Camden Yards (3:05 p.m.), 20 years after one of the biggest moments in not just the franchise’s history, but all of baseball’s. Yes, 20 seasons ago, on a September night in baseball’s first new “old” ballpark, Cal Ripken Jr. broke what was considered the most unbreakable streak in baseball, playing in his 2,131st consecutive game.

As he sat on a modest stage at a table with fellow baseball dignitaries Joe Maddon and Dave Winfield before his Cal Ripken Sr. Aspire Gala in February, Ripken seemed to be caught off guard that it had been 20 years since his indelible moment.

“I’ve been out since 2001, and it’s amazing how fast the time flies once you go out,” Ripken said of the end of his career. “Looking back, it’s hard to believe it’s been 20 years.”

When you strip away the pomp and circumstance, the legend that has sprouted around it, it’s a bit of an odd achievement. He didn’t have the most hits or home runs or any other measurable achievement on the field. He just played every day.

There’s something to that, though, in baseball and in life. Baseball is very much about showing up at the ballpark every day. It’s about surviving the grind that playing nearly every day for six months takes on not just your body, but your mind as well.

Every ball off the end of the bat or the handle sends shock waves into your wrists. Every hard-sliding runner from first can clip a bit of your knees or ankles with their spikes as you try to turn two. Ripken was hit by more than 40 pitches during The Streak — none cost him a game.

There’s also the hidden wear and tear that the grind takes. Three flights or long bus rides every two weeks, to a pair of road cities and home again. Sleeping in hotel beds. Late-night turnarounds into getaway days.

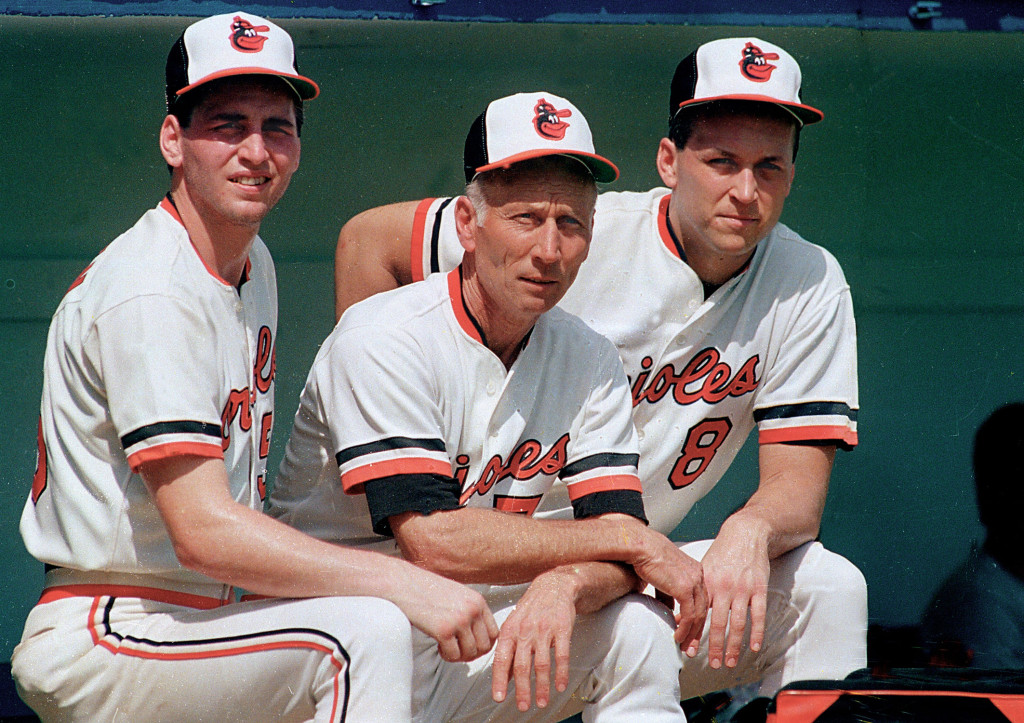

Anyone could be forgiven for taking a day off over the years, especially during the years that The Streak spanned, in which the Orioles made the playoffs just once — when they won the World Series in 1983 — and finishing fourth or worst in their division seven times. And yet, Ripken didn’t.

Between 1982 and 1995, Ripken not only showed up to play every day; he played at a Hall of Fame level. As a shortstop, he led baseball in total bases (3,878) and extra-base hits (816), was second in doubles (447) and RBI (1,267), tied for second in home runs (327), was third in hits (2,366) and fourth in runs scored (1,271). He ranked second in the majors in WAR (85.1), trailing only Rickey Henderson.

Just like the man whose streak he broke, he ascended to a higher level because of it.

“It was a great moment for baseball, kind of connected [to] that record that was set by Lou Gehrig,” Ripken said. “It was sort of a bridge from that old feeling of when it was a game to more of modern baseball.”

More than that, it was the first moment that lifted baseball out of its self-dug abyss. One of the ugliest moments in the game’s history was the labor strike of 1994, which cost us all the World Series. Many fans shunned America’s Pastime in the immediate aftermath, and some say it still affects their passion today. While the home run chase of 1998 may have been the final step to fully restoring baseball to its pre-strike popularity (attendance jumped over 70 million in ’98 after bottoming out just over 50 million in ’95), Ripken’s moment was an enormous step.

Other than President Bush’s first pitch following the 9/11 attacks in 2001, when has a sitting president (accompanied by his vice president, no less) attended a regular-season game as a dignitary to honor a player?

But President Clinton was just one of many celebrities there that night. Joan Jett sang the national anthem and presented Ripken with a gold record. David Letterman prerecorded a Top 10 list of reasons Ripken should take a day off, which was shown on the Jumbotron.

And the entire game came to a stop after Mike Mussina induced a pop-up to end the top of the fifth with Baltimore leading 3-1, making the contest official. That set off an impromptu celebration that lasted more than 22 minutes. After Ripken had already come out three times for standing ovations, he was pushed out of the dugout by teammates and completed a full victory lap around the ballpark.

In the box, the owner of baseball’s other untouchable streak, Joe DiMaggio, a teammate of Gehrig’s, cried. Teammates stood and applauded as well, along with the umpires and members of the opposing team, the California Angels.

“One of the cool parts about that night was being able to go around and embrace every one of the members of the Angels as you went around that lap,” said Ripken. “There were great human moments in there.”

Of course Ripken homered in the game. Of course the Orioles won. Everything played out according to script, better than anyone could have planned. As the rookie Mark Smith said before the game, it was what baseball needed. The nation seemed to know it at the time, even if the sharp edges of the memory may have faded beyond the boundaries of Eutaw Street.

“I know I’ve heard other guys who, when they get removed from the game, say ‘the game was better when I played’ — I’m not one of those guys,” Ripken said. “I think the game continues to evolve. I think it’s a great game and it’s better now, better than ever.”

Indeed, the game today is as strong as it ever could have hoped to become on that September evening. The Orioles are in good shape on the field as well, coming off an AL East title with reason to hope for another. But as much as the franchise owes to Ripken, Major League Baseball may owe more.

“Anybody that comes through baseball, you try to make a contribution to the game while you’re playing,” he said. “Hopefully you’ve made a contribution and left your mark in a positive sense, and then you hand it off to the next generation of guys.”

It was classic Ripken, perhaps the biggest understatement he could have possibly made about the lasting impact of his career.

Last September, Hunter Pence got a day off after the San Francisco Giants clinched a playoff spot. At the time, he was the active leader in consecutive games started, with all of 331. The longest streak in baseball today? Fewer than 200 games.