Virginia may have found an unexpected ally in the battle against one of the region’s most destructive invasive species: the common ant.

Led by Assistant Professor Scotty Yang at Virginia Tech, a team of researchers discovered a surprising new way to detect the presence of spotted lanternflies — by analyzing the ants that unknowingly track them. The breakthrough, recently published in the Pest Management Science and Neobiota online journal, could transform how we spot invasions before they take hold.

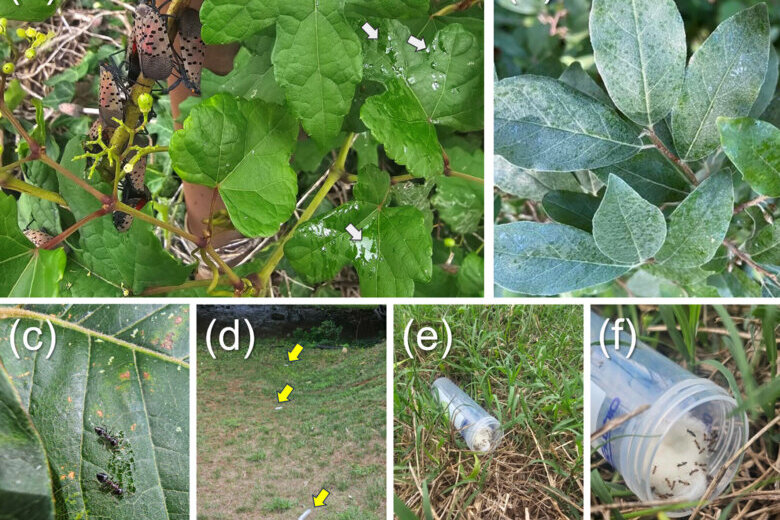

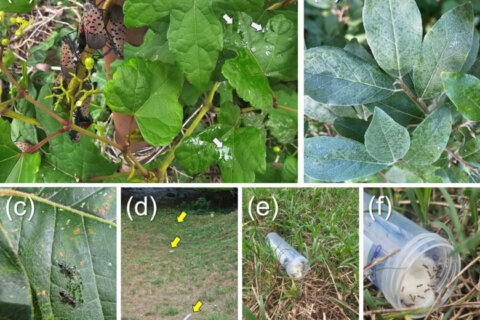

Originally from Asia, spotted lanternflies have been spreading across the U.S. since 2014, leaving behind a trail of damage in vineyards, orchards and even backyard trees. The bugs feed on plant sap using strawlike mouthparts and leave behind a sticky substance called honeydew — rich in sugars and, it turns out, full of lanternfly DNA.

That’s where the ants come in.

“Ants are nature’s sugar seekers,” Yang explained. “They’re always on the move, looking for food, and they love honeydew.”

When ants find that sugary waste, they eat it, bring it back to their nests, and share it — unknowingly carrying traces of spotted lanternfly DNA in their bodies.

Using environmental DNA testing — a tool often used to detect wildlife without ever seeing the animal — Yang’s team developed a new method called antDNA. By collecting foraging ants and analyzing them in a lab using PCR testing, researchers were able to detect lanternfly DNA even when no actual bugs were seen.

In some cases, the ants picked up DNA from more than 300 feet away from the nearest known infestation, with traces lasting up to five days after a single meal.

Early detection is critical when it comes to spotted lanternflies. These pests threaten grapevines, hops, hardwood trees and more. Once they’ve settled in, removing them becomes difficult and costly. Traditional detection methods rely on physically spotting the bugs or their eggs — often too late. The antDNA method offers a faster, more scalable solution.

And because ants live almost everywhere — forests, fields, cities — this approach works in all kinds of environments.

Yang’s team is now working on a portable testing kit, allowing real-time results in the field. In the future, this method could be used to detect other honeydew-producing pests, offering a broader defense for crops and ecosystems alike.

By turning one of nature’s most tireless scavengers into a tool for early warning, Virginia Tech researchers may have given farmers, scientists and city officials a much-needed edge in the fight to protect trees and crops.

The original study is online.

Get breaking news and daily headlines delivered to your email inbox by signing up here.

© 2025 WTOP. All Rights Reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.