This article was republished with permission from WTOP’s news partner InsideNoVa.com. Sign up for InsideNoVa.com’s free email subscription today.

This article was written by WTOP’s news partner InsideNoVa.com and republished with permission. Sign up for InsideNoVa.com’s free email subscription today.

It’s the first Tuesday of the month, and a different type of hearing is going on in Prince William County Circuit Court.

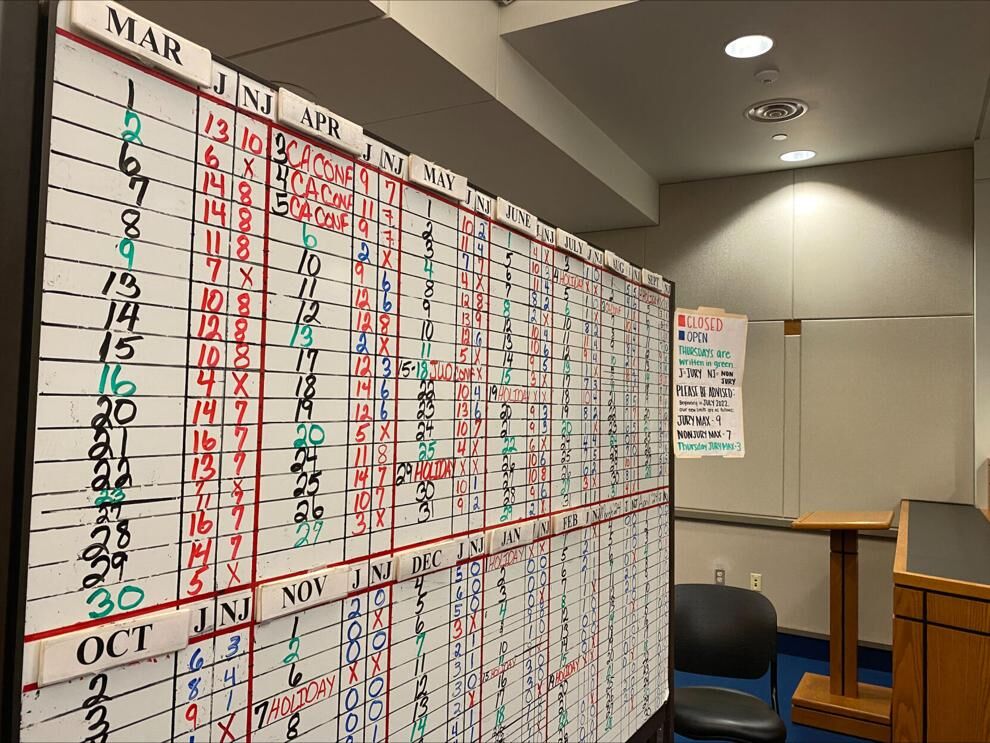

In courtroom No. 5 is a roughly 4-foot-by-7-foot whiteboard on wheels sitting in front of the jury box. It has a dizzying multicolored chart that takes a few minutes to process.

The board lists the working days of each month. Next to each day are two columns: one for the number of scheduled jury trials and the other for the scheduled non-jury trials. Although there is some green and blue, there are a lot of red numbers on the chart.

It’s term day, and you’re about to witness a microcosm of the increasingly strained local court system. Every month, anyone who needs to schedule a hearing or criminal or civil trial comes to the courthouse to get a date on this calendar.

In the gallery, attorneys are squinting at the board and checking their phones or papers. They call out case names to find the opposing counsel. The lawyers then huddle for a hushed conversation before returning to examine the board.

About 30 minutes later, a sheriff’s deputy enters and announces the arrival of Chief Judge Kimberly Irving. Irving takes her seat on the bench and dons a pair of glasses. She starts calling out cases one by one. Term day has started.

Prince William has seven circuit court judges who theoretically can preside over only seven trials a day in total across all civil and criminal cases. If judges limited scheduling to those numbers, the system would grind to a halt. Instead, they massively overbook days with the hope that cases will be resolved outside of trial before their scheduled day.

The whiteboard has a small attached sign noting the maximum scheduling guidelines. Its limits are nine jury trials and seven bench trials a day, for a total of 16 trials, whether they are criminal or civil.

If only it were that easy.

At the February term day, dozens and dozens of days had many more trials than the maximum. Of the 19 days available for trials in March, six had more than 14 jury trials. Seven days had more than 21 total trials and three had more than 23 trials.

“Very often we’re overbooking the court by sometimes 12 jury [trials],” said Commonwealth’s Attorney Amy Ashworth.

Ashworth said that although there’s some remaining backlog from the COVID-19 pandemic, caseloads are pretty similar to previous years. So how did we get here?

One cause: Sentencing changes

A commonly cited potential cause for the situation is recent changes in criminal sentencing procedures.

Defendants in criminal cases have always had the right to a jury trial. In Virginia, if a case went to a jury trial before July 1, 2021, and the defendant was found guilty, the jury would provide a sentencing recommendation. Although judges have the final say on the sentencing and could reduce it, they rarely went against the jury’s recommendation.

In cases before July 1, 2020, while juries were determining the recommendation, they were not allowed to know the sentencing guidelines and thus had to come up with a number on their own, which wound up being typically higher than the guidelines. After July 1, 2020, juries are informed of the guidelines but are not allowed to recommend anything other than jail time, requiring at least a minimum sentence.

For example, if someone was convicted of a robbery, the lowest recommendation could be five years in jail.

Because of this, defendants would typically opt for a bench trial, in which the judge determines guilt and sentencing. While avoiding a guilty verdict might be more difficult with a judge, sentencing could be lighter because judges are allowed to operate outside sentencing guidelines and can consider alternatives to incarceration.

“There was almost an incentive built into the system to not have a jury trial,” Ashworth said.

However, starting July 1, 2021, Virginia allowed defendants to opt for a jury trial but have a judge do the sentencing. Essentially, it allows defendants to pick both the better chance for a not-guilty verdict and the better chance for a shorter sentence.

Local attorneys and judges say this change has caused requests for jury trials to skyrocket in the past 18 months. These proceedings take much longer than bench trials because attorneys have to establish legal terms and procedures that judges already recognize, and juries have to be selected.

“Now it’s unusual at term day for a [criminal] defense attorney to request a non-jury trial,” Ashworth said.

When Ashworth worked in the prosecutor’s office before being elected, she typically had three to four jury cases a month scheduled but only about one every other month actually went to trial. Now prosecutors have jury trials pretty much every week. She said it’s caused “a large increase in workload.”

“When you’re going to do a bench trial, you’re not going to practice your opening statement, you’re not going to memorize your opening statement for a judge,” Ashworth said.

In February, all the criminal cases were set for jury trials or plea hearings.

Scheduling criminal cases will always take precedence because of speedy trial requirements under the constitution. Trials must be held within nine months of an indictment or a preliminary hearing, whichever is first. If a defendant is incarcerated, that requirement shrinks to five months. Defendants are entitled to a trial in that timeframe and are required to waive that right to go beyond it.

The situation is creating burnout, Ashworth said. “We have lost quite a few prosecutors.”

Civil cases come later

Because criminal cases come first, those attorneys get the first crack on term day. In the afternoon, civil and domestic cases get scheduled. However, just because those civil cases get scheduled doesn’t necessarily mean they will be heard when the date comes up.

While that might not seem like a big deal for lawsuits against businesses or property disputes, it can present problems in domestic relations cases. For example, it could take longer for a divorce to be finalized or for custody issues to be resolved.

“You’re putting families on hold, which is not a good way to serve our community,” Ashworth said.

Cassandra Chin, who practices family law in Prince William, said things have improved since the seventh judge was added to the circuit last year.

Chin said family law usually has two types of cases: pendente lite and final hearings. Pendente lite is a latin phrase that means “pending the litigation,” and these hearings provide solutions to immediate issues until a final hearing. Those usually last only two hours, while final hearings can take multiple days.

Issues that could be heard in a pendente lite hearing are child support or custody. Although they take less time, they are more likely to be put on hold because of criminal trials running longer. Chin said it could take six months or longer to have a multiday final hearing scheduled.

“I think our judges in general are very accommodating,” she said. “If it’s not heard that day, you can usually get an alternate day in a matter of weeks.”

When trials go longer, officials sometimes must scramble to find an available judge to hear other cases.

Chin, however, believes the court is conscious of the issues in domestic cases and won’t delay hearings unless absolutely necessary. “The court does try very hard to get those cases assigned to a judge so there’s not significant delay.”

Possible Solutions

Ashworth believes the prosecutor’s office is doing its best to help through diversion programs. However, it’s hard for those to run efficiently without adequate staffing because prosecutors still need to review cases and determine whether they’re right for diversion.

Unfortunately, the programs have created a double-edged sword in funding the commonwealth’s attorney’s office.

The office receives funding from the local government and the State Compensation Board. The state allocation is based on a formula relying on how many cases are taken to a grand jury and the number of felony sentencing events.

Because diversion programs essentially remove cases from the docket, they reduce the numbers used by the state and can lead to fewer dollars for the office. Ashworth said this encourages prosecutors to take felonies to a grand jury that are more proper for a reduction to a misdemeanor through a plea bargain.

“That formula has a lot of problems with it,” she said. “The commonwealth has always done prosecution on the cheap.”

For now, prosecutors, attorneys and judges are being forced to make do with the cards they’re dealt.

Irving, who declined to comment, has spoken about the situation to the Board of County Supervisors. When the local system added the seventh judge, she said they already need another.

“We needed eight last year,” she told the board. “We are absolutely in dire need around the courthouse.”