Road signs depicting deer at popular crossings help give drivers fair warning, but Virginia will now be helping animals avoid roads entirely.

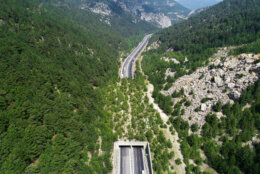

Wildlife Corridors in Virginia might include grassy overpasses similar to those used by elk in western portions of the U.S. or mimic a system that is already in use in Florida.

“In Florida you see underpasses — essentially culverts where small mammals and reptiles and frogs and toads can get through,” Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources Chief of Wildlife Gray Anderson said.

Plans and a project task list will be created by a leadership team comprising members from the Department of Game and Inland Fisheries, the Department of Transportation and the Department of Conservation and Recreation.

“We’re still in the very early planning stages trying to figure out which of those [over or under roads] best works for Virginia and where,” Anderson said. “Virginia is very unique in how our people are spread across the street and then how our wildlife are spread across the state.”

A 2016 study in rural southwest Virginia conducted on behalf of State Farm counted 64 different species of roadkill. Of the 1,837 animal casualties counted, there were 1,415 mammals, 188 birds, 105 reptiles, 122 domestic animals and seven frogs.

The intention of the Wildlife Corridor action plan is to promote safety for drivers and help wildlife when roads cut through wetland habitats, for example.

“We have deer and bear crossing the roads in hazardous ways,” Anderson said.

There’s also the goal of conservation.

“Say … the various salamanders that need to cross from one wetland to the other — that’s a very different problem,” Anderson said. “It’s not a human health and safety issue; it’s really about trying to help that population.”

The group’s task is to remedy current situations and plan for future transportation projects to give consideration for the needs of both people and nature.

“Thinking on where these future transportation corridors are going to go, so we can build smarter, more conservation minded into the future,” Anderson said. “So when a new road does need to go in, we focus on maintaining that continuity between the two habitats on either side of the road if they need to be maintaining wildlife.”