Monday at 2 p.m. EST, controllers at the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) Mission Operations Center commanded the telescope to fire its onboard thrusters for five minutes. At 2:05 p.m., JWST officially arrived at the second Sun-Earth Lagrange point known as L2, 30 days after being launched on Christmas Day.

Located 1 million miles from Earth, L2 is JWST’s permanent home in space.

The original schedule indicated this would happen at 29 days after launch, but an extra day was added for logistical reasons for the team and worldwide ground resources. The extra day had no impact on the mission.

For “insertion into the L2 orbit, it was not that critical of a final burn,” according to NASA and Northrop Grumman representatives at a media teleconference held after the successful maneuver.

They also commented that the final fuel available amount will be forthcoming, which is the determining factor for mission length, adding that “JWST will not need to be refueled.”

The last mission length estimate provided following the previous midcourse correction maneuvers was 20 years. Hints were given Monday that JWST’s available fuel may exceed that previous estimate. Five years was the minimum for JWST mission success but officials hoped for 10 years.

From launch to L2, NASA; partner European Space Agency; Canadian Space Agency; Northrop Grumman; and the thousands of scientists, engineers and workers, involved in JWST were living “29 Days On The Edge.”

Why? Simple. JWST had to successfully progress through 344 single points of failure; the occurrence of any one of them would put the mission in jeopardy.

Of the 344, only 49 are left, and “they will not be retired for the duration of the mission; 15 are with the instruments while others involve propellant tanks and other items on JWST,” representatives said during Monday’s teleconference.

NASA and Northrop Grumman representatives let out a “huge sigh of relief with getting to L2 as well as the major prior deployments of the mirrors and sunshield.” Controlling JWST involves 95 people in the Mission Operations Center for each shift, plus others from Northrop Grumman.

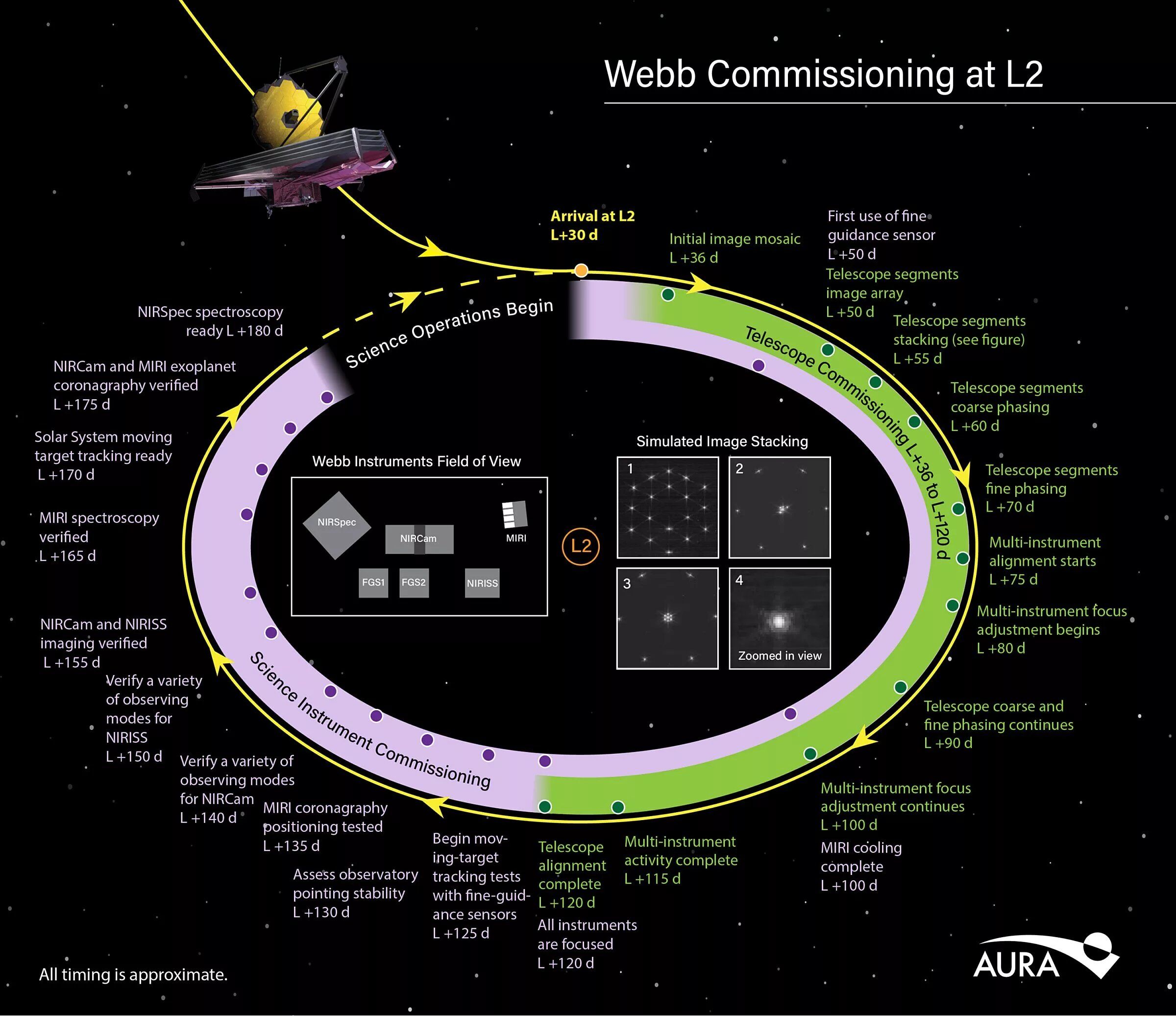

With the telescope in its permanent L2 home, the next five months will involve preparing it for commissioning, the point at where the mirrors of the optical system are focused (about three months) and the instruments checked out, cooled down and ready to begin science operations (about two months).

The next three months are going to be all about getting the 18 hexagonal segment mirrors aligned and in focus with the deployed secondary mirror. Another big deployment milestone recently completed was the successful release of all 18 mirror segments from their stowed launch position which will now allow actuators on the back of the segments to be used to achieve alignment and focus. A bright, isolated star — one that had no other nearby and bright stars — would be used for the process.

Being a longtime telescope user, I asked if they had identified the star they were going to use. They identified it as HD 84406, a somewhat bright star similar to the sun located in the Big Dipper. It can’t be seen with the unaided eye, but it is visible in binoculars and telescopes.

I took up the challenge to find the star and last night, I imaged HD 84406 with my 4.5-inch Unistellar telescope. It is a pretty yellowish star that is indeed devoid of any close bright stars. I imagined how the view of the star will be in each of the 18 mirror segments as they align them to act as one mirror with the secondary mirror.

Once commissioning is completed, estimated to be in early summer, the briefing team spoke about the release of “wow images for the public” that will show what JWST is capable of.

They were rightfully coy about what the largest space telescope ever deployed would show us but they were pretty excited about it. So am I.

Follow Greg Redfern’s daily blog to keep up with the latest news in astronomy and space exploration. You can email him at skyguyinva@gmail.com, or follow him on Twitter.