If you told a teenager today that snapping a photograph used to require buying film in advance, paying and waiting to have the film developed, the response would likely be “SMH,” or “shaking my head,” for those not steeped in social media.

Steven Sasson, the patent-holder for the world’s first digital camera, told WTOP he’s amazed that his invention has become ubiquitous: “I’m as surprised as anybody,” he laughed.

In 1974, Sasson was working for Kodak.

“I was challenged with getting a new type of imaging device, called a charge-coupled device, into the company — to play with it, and see if there was anything useful we could do with it,” Sasson said.

A charge-coupled device is a light-sensitive integrated circuit that captures images by converting photons to electrons.

“I was storing basically an electronic image in a memory system that I had put together,” Sasson said. “I said, ‘I’m creating kind of an electronic still camera.'”

Snapping the photo was only the first challenge: “I then proceeded to build a playback system that would allow us to actually view the image that I’ve captured.”

Sasson took his first picture using the camera and displayed it in December, 1975. His patent was filed with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office in May of 1977 and was granted in December of 1978.

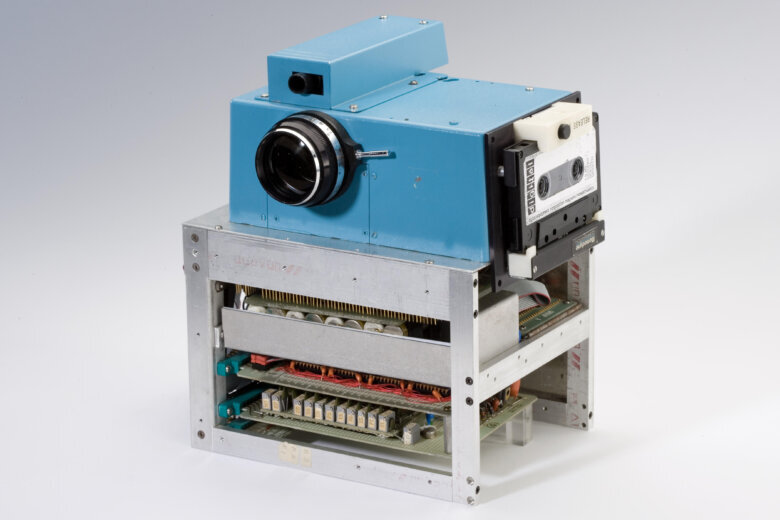

His 1975 prototype digital camera system was a far cry from today’s tiny, self-contained smartphone cameras and professional-grade digital cameras.

“It was about the size of a toaster. It weighed about 8 pounds or so,” Sasson said.

The device captured black-and-white images on a digital cassette tape, which at the time was the preferred way for music lovers to record music-to-go.

“If you bought them from Philips, they cost you a lot of money. But, if you went down and bought a Memorex audio cassette, that worked just as well,” Sasson said.

While today’s digital cameras instantly save an image on a camera roll, the process was far more involved in 1975.

“It was a very quick capture with available light, but it was digitized and stored in an onboard digital memory. And then, from there, it was slowly recorded to the audio cassette, because it had very limited bandwidth. That took about 23 seconds, as I remember,” Sasson said.

The image quality was rudimentary: “My original prototype only had 10,000 pixels, or .01 megapixels,” he said. “I think the latest iPhone has 48 megapixels.”

Missed opportunity?

In 1975, while he was demonstrating his prototype in Kodak conference rooms, company leaders were torn.

“They asked me, ‘When do you think it would be practical and actually in consumers’ hands?’ And I thought between 15 and 20 years,” Sasson said. “It turned out to be not a bad prediction.”

At the time, Sasson’s invention clashed with Kodak’s business models — he could take a picture by only consuming a few joules of energy, without the need for film or printing paper.

“It was instant, but it didn’t result in any consumables being used,” Sasson said. “Of course, that went against Kodak’s business model at the time, so it wasn’t too well received.”

Kodak decided to remain focused on its core business, involving film and paper.

“The first consumer digital camera that took color pictures that was reasonably priced was put on the market by Apple,” in 1994, Sasson said. “It was designed and built by Kodak. It was called the QuickTake 100, and it looked a bit like binoculars, sorta flat.”

Sasson went on to say, “It might seem odd to people that Kodak would build the first digital camera, but not claim it. That was simply because we were still afraid of cannibalizing film … We had the technology, we just didn’t have the business plan on how to deal with it.”

Sasson will take part in the 50th Anniversary Induction Ceremony for the National Inventors Hall of Fame on Oct. 26 at The Anthem, in Southwest D.C.

He has enjoyed watching the evolution of his invention into a technology that most people carry in their pockets, and the crystal-clear quality of images.

“I had no idea it would advance this fast in my lifetime,” Sasson said. “I thought, ‘if we could get to 2 million pixels, boy that would be great.’ I’m as surprised as anybody.”