▶ Watch Video: The price of free speech – and censorship

When someone says something we disagree with, should we shut them up? In 1927, Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis had an answer: “The remedy to be applied is more speech, not enforced silence.”

Well, in that case, the internet should have solved everything, notes correspondent David Pogue – it’s nothing but more speech. And yet lately, the news is full of stories about people trying to limit other people’s expression:

- Florida lawmakers are advancing a pair of bills that would bar school districts from encouraging classroom discussions about sexual orientation or gender identity – what critics are calling “Don’t Say Gay” bills.

- Nearly a dozen states have introduced bills that would direct what students can and cannot be taught about the role of slavery in American history and the ongoing effects of racism in the U.S. today.

- A Tennessee school board removed “Maus,” a Pulitzer Prize-winning graphic novel about the Holocaust, from its curriculum.

- Spotify faced growing controversy over episodes of Joe Rogan’s podcast containing racial slurs and COVID-19 misinformation.

- An incoming Georgetown Law administrator was assailed by a student group for posting a “racist, sexist, and misogynistic” tweet that criticized President Joe Biden’s announcement that he would nominate a Black woman for the Supreme Court.

“I would argue that the culture of free speech is under attack in the U.S.,” said Jacob Mchangama, the author of “Free Speech,” a new book that documents the history of free expression. “And without a robust culture of free speech based on tolerance, the laws and constitutional protection will ultimately erode.

Basic Books

“People both on the left and the right are sort of coming at free speech from different angles with different grievances, that point to a general loss of faith in the First Amendment.”

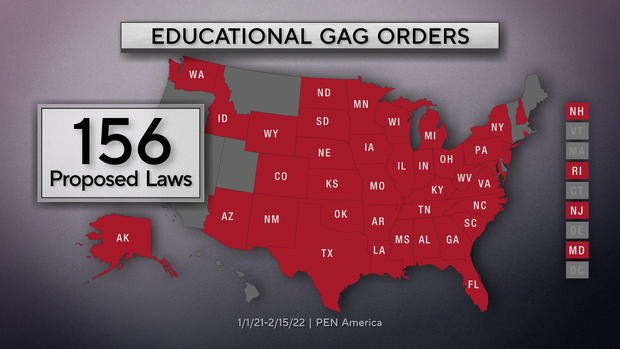

The free-speech erosion is even happening in schools. Since January last year, according to PEN America, Republican lawmakers have introduced more than 150 state laws that would restrict how teachers can discuss race, sexual orientation, and gender identity in the classroom.

Jennifer Given, who teaches high-school history in Hollis, New Hampshire, said of the laws, “It’s about making up false narratives to further a political goal of your own.

“It’s a really scary time to be a teacher,” she told Pogue. “We’re self-censoring, We are absolutely avoiding certain things and ideas in an effort to stay within the lines as best we understand them.”

In New Hampshire, a new law limits what teachers can say about racism and sexism – and a conservative group is offering a $500 bounty to anyone who turns in a teacher who violates it.

Given said, “The ghost of Senator McCarthy is alive and well in some of our state house hallways.”

Pogue asked, “What would happen to you if you did step afoul of this law?”

“That can result in the loss of your license,” she replied. “And so, I would not only be unemployable at my school, but I would be unemployable anywhere.”

“But what I don’t understand is, this is New Hampshire, whose motto is, ‘Live Free or Die’!”

“Yeah, yeah,” Given laughed. “There’s a lot of emphasis on the ‘or die’ part of late!”

UC Berkeley professor John Powell, an expert on civil liberties and democracy, said of the classroom prohibitions, “That’s a very serious freedom of speech issue. To me, that is so far off the rail.”

He’s especially alarmed at the record number of books that are being banned in schools all over the country. Conservatives object to books about sex, gender issues, and racial injustice (such as Toni Morrison’s “Beloved,” Alex Gino’s “George,” and “The 1619 Project”), and liberals object to books containing outdated racial depictions (including John Steinbeck’s “Of Mice and Men,” Mark Twain’s “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn,” and Harper Lee’s “To Kill a Mockingbird”).

- 10 Most Challenged Books Lists (American Library Association)

- Virginia school board officials suggest burning books banned from schools (“Red & Blue”)

“You can’t make the Holocaust a nice thing – it wasn’t a nice thing!” Powell laughed. “You can’t make slavery a nice thing. ‘That makes people uncomfortable.’ It should make people uncomfortable! The goal of education is not comfort. So, if someone really wants to challenge the Holocaust, let ’em challenge it. But don’t ban a discussion on it.”

In the mid-1800s, English philosopher John Stuart Mill proposed that governments limit free speech only when it would cause harm to others.

Powell said, “He wrote a book called ‘On Liberty,’ [about] freedom. And he was very concerned about the government silencing people, that citizens had to have the right to express themselves.”

Our laws have generally followed that guideline. In the U.S., public speech can’t include obscenity, defamation, death threats, incitement to violence – harms.

But Powell said that the recent restrictions have more to do with culture wars than with preventing harm: “I want to regulate that ’cause I don’t like it. To me, that’s wrong. That’s problematic.”

“So, there’s a difference between saying something that makes you uncomfortable, and saying something that damages society or incites to riot?” asked Pogue.

“Right, and discomfort is not the same as an injury.”

But these days, there are entire new categories of speech that can lead to harm. “Now, there’s a concept of disinformation, where you deliberately engage in lies, in fact to cause harm, to cause injury, to exclude some people,” said Powell. “But what it really means is our understanding of the First Amendment and our understanding of free speech is evolving. It has to evolve.”

It’s probably no coincidence that the new censorship culture arose simultaneously with social networks like Facebook and Twitter.

“The First Amendment was conceived as a protection of citizens from restriction of expression by the government, and not by private companies or other entities,” said Jillian York, the director for international freedom of expression at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, and author of “Silicon Values.”

Pogue asked, “So for example, Donald Trump getting kicked off Twitter and Facebook? Is that censorship? Is that bad censorship? Is that good censorship?”

“I think Trump getting kicked off of Facebook and Twitter is kind of complicated,” York said. “But the thing that really concerns me the most is that someone like Mark Zuckerberg, whom none of us elected, has the power to remove an elected official. I think that should really worry us, even if we do feel that Trump should be silenced.”

York said that the big tech companies censor our speech every day, sometimes by mistake, but always without supervision or transparency. “We saw protest content around Black Lives Matter removed on Facebook’s platform, wrongfully,” she said. “LGBTQ content has been removed. as well as things like art and satire.”

- Faceoff against Facebook: Stopping the flow of misinformation (“Sunday Morning”)

- Texas governor signs law prohibiting social media platforms from banning users

- Lawmakers vow stricter regulations on social media platforms to combat misinformation

According to Jacob Mchangama, social networks censor us in another way, too, by making us afraid to speak at all: “There was actually this survey from 2020 by the Cato Institute which showed that 62% of Americans self-censor, who are afraid to sort of express their political views on specific topics.

“It shows this paradox: Americans enjoy the strongest legal constitutional protection of free speech probably in world history. But they still fear the consequences of being fired for speaking out on certain political views. And that’s not a healthy sign.”

But it’s not just America. Since 2019, at least 37 countries have passed laws that increase censorship (of individuals or the media), including in Europe, where Jillian York lives. “There’s a lot of debate right now in Germany, for example, over a fairly recent law that restricts hate speech online,” York said, “but also creates penalties for things like the country’s insult law. So, you know, insulting someone online could be penalized financially.”

Overall, it would be easy to get depressed by these attacks on free speech. Especially if you’re a teacher, like Jennifer Given.

Pogue asked, “What’s the end point for you, if this keeps going this way in New Hampshire?”

“I don’t know,” she laughed. “There is a point where you start going, ‘Maybe I’ve had it.'”

But if it cheers you up any, Jacob Mchangama points out that we still enjoy more freedom of speech than most countries: “If we were having this discussion in Russia or Turkey, you know, someone would pick me up when I go down on the street, and you might not hear from me for a long time.”

He said we should fight to maintain our freedom of civil discussion – and never take it for granted.

“I’m not saying that free speech is just great, and doesn’t entail any consequences; it does,” he said. “You know, we should think about, how do we mitigate misinformation? How can we ensure that we counter hate speech without compromising free speech?

“And, you know, it’s an experiment. But I would argue that it’s been a very beneficial experiment. And one which is very much worth continuing.”

For more info:

- “Free Speech: A History from Socrates to Social Media” by Jacob Mchangama (Basic Books), in Hardcover, eBook and Audio formats, available via Amazon and Indiebound

- Follow Jacob Mchangama on Twitter

- John A. Powell, professor, University of California, Berkeley School of Law

- “Silicon Values: The Future of Free Speech Under Surveillance Capitalism” by Jillian C. York (Verso), in Hardcover, eBook and Audio formats, available via Amazon and Indiebound

- jilliancyork.com

- Electronic Frontier Foundation

- Jillian York photo: Nadine Barišić

Story produced by Mark Hudspeth. Editor: Mike Levine.

See also

- Censorship on social media? It’s not what you think (CBS Reports)

- The psychology behind “cancel culture”: Is it justice or censorship?