▶ Watch Video: Supreme Court considers gun ban for domestic abusers

Washington — The fallout from the Supreme Court’s landmark Second Amendment decision handed down last year was on display Tuesday when the justices weighed a high-stakes case that pits the right to bear arms against a federal law that seeks to protect victims of domestic violence by keeping guns away from their alleged abusers.

Arguments in the dispute were the first heard by the court since its conservative majority imposed a new test for assessing whether a firearms restriction passes constitutional muster, which has sparked confusion and frustration among the nation’s federal judges as they navigate new challenges to longstanding laws.

Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar, who represents the government before the Supreme Court, urged the justices to correct what she said was the “profound misreading” of their June 2022 decision in New York State Rifle and Pistol Association v. Bruen, which has had “destabilizing consequences” and led to invalidations by lower courts of widely accepted gun restrictions like those disarming convicted felons.

“History and tradition confirm common sense,” she said in closing remarks. “Congress can disarm armed domestic abusers.”

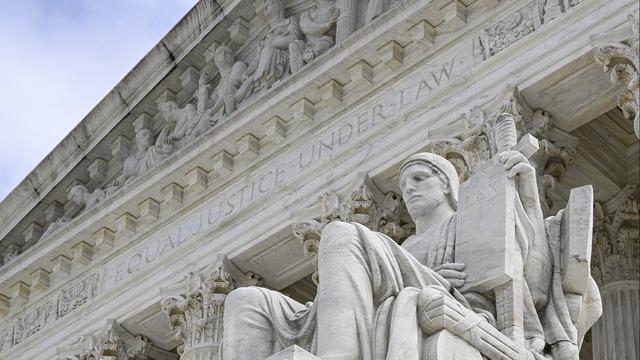

The Supreme Court is seen in Washington, D.C., on Oct. 9, 2023.

The Supreme Court is seen in Washington, D.C., on Oct. 9, 2023.

MANDEL NGAN/AFP via Getty Images

The justices appeared inclined to agree, with some of the court’s conservative members focusing their questions on Prelogar’s argument that the history and tradition of the Second Amendment allows for gun ownership to be limited to “law-abiding, responsible” citizens. They indicated a belief that those deemed dangerous to society could be disarmed after raising concerns with the reach of Prelogar’s suggestion that people considered irresponsible would not be covered by the Second Amendment.

“Responsibility is a very broad concept,” Chief Justice John Roberts said, asking Prelogar, “What is the model? Do you go back to what was irresponsible at the common law or take a poll?”

Justice Amy Coney Barrett said that if she agrees there is a historical tradition that “shows that the legislature can make judgements to disarm people consistently with the Second Amendment based on dangerousness, why can’t I just say that?”

Apart from presenting the court with the opportunity to clarify its gun rights decision issued last year, the proceedings were set against the backdrop of the latest mass shooting to rattle an American community, less than two weeks a gunman killed 18 people in Lewiston, Maine, which has again prompted calls for federal action to combat gun violence.

Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson referenced the shooting in Maine, questioning how a state lawmaker there would approach possible legislative responses under the standard laid out by the high court in its decision last year.

U.S. v. Rahimi

The dispute before the justices, known as U.S. v. Rahimi, involves a law enacted by Congress nearly 30 years ago that prohibits people under domestic violence restraining orders from having firearms. Zackey Rahimi, a Texas man, was subject to such a restraining order granted to a former girlfriend in February 2020 when he threatened another woman with a gun and fired guns in public on five separate occasions in December 2020 and January 2021.

Following the incidents, police found two guns at his residence while executing a search warrant. Rahimi was indicted under the 1994 law and pleaded guilty, but challenged the constitutionality of prohibition, arguing it is unconstitutional under the Second Amendment.

The 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ultimately tossed out Rahimi’s conviction and struck down the gun law under a new legal test for determining whether firearms restrictions comport with the Constitution.

Under that test, set forth by the Supreme Court in its landmark decision nearly 17 months ago, the government must put forth laws that are analogous to the modern-day measure in question in order to show that it fits within the nation’s history and tradition of firearms regulation.

The 5th Circuit said the analogues offered by prosecutors during its historical inquiry “fall short,” and concluded that law “falls outside the class of firearm regulations countenanced by the Second Amendment.” The Justice Department appealed to the Supreme Court, which agreed in late June to review the 5th Circuit’s decision.

The court’s oral arguments

During Tuesday’s oral arguments, Justice Elena Kagan acknowledged what she said was a “fair bit of division and a fair bit of confusion” among the lower courts about what is required under the test laid out in the Bruen decision, and invited Prelogar to recommend guidance the Supreme Court can give about how to apply its framework.

The Biden administration has said that history and tradition establish that the Second Amendment allows Congress to disarm people who are not “law-abiding, responsible citizens,” and cited laws dating back to the founding that disarmed people found to be dangerous. Prelogar also warned that the presence of a gun substantially increases the chance of domestic violence escalating to homicide.

“Guns and domestic abuse are a deadly combination,” she said during opening remarks to the justices, adding that the court has recognizing that “the only difference between a battered woman and a dead woman is the presence of a gun,” a reference to an opinion written by Justice Sonia Sotomayor for a unanimous court in 2014.

As a result of the law, the national background check system has prevented more than 77,000 gun purchases by people subject to domestic violence restraining orders since its inception in 1998, said Jennifer Becker of the Battered Women’s Justice Project.

“This is not about taking everyone’s guns away,” Becker said before arguments. “This is about temporarily taking guns away from people who have been determined by a court to be currently dangerous.”

But Rahimi, represented by federal public defenders, said in a filing to the justices that there is nothing akin to the federal law disarming people under domestic violence restraining orders in the country’s historical tradition, which means the measure is unconstitutional under the court’s framework.

“Although a ‘historical twin’ is not necessary, the government cannot point to a close relative, a distant cousin, or anything bearing even a passing resemblance,” Rahimi’s lawyers wrote.

At the Supreme Court, there seemed to be agreement that Rahimi specifically should not have access to weapons, and Roberts asked Matthew Wright, an assistant federal public defender representing Rahimi, whether he had any doubt “that your client is a dangerous person.”

“Someone who’s shooting at people, that’s a good start,” he said.

Wright faced sharp questions about his position, with Barrett declaring, “I am so confused.” Kagan, meanwhile, accused Wright of “running away” from his argument because its implications are “untenable.”

“It seems to me that your argument applies to a wide-variety of disarming actions, bans, what-have-you, that we take for granted now because it’s so obvious that people who have guns pose a great danger to others and you don’t give guns to people who have the kind of history of domestic violence that your client has or to the mentally ill or what-have-you,” she said.

A clash over gun rights

The case is the first involving gun rights that the justices heard following their June 2022 decision, and it presented the court with its first opportunity to clarify how lower courts should apply the so-called history-and-tradition test. Since the court’s 6-3 conservative majority issued its Second Amendment ruling, courts weighing challenges to widely accepted firearms laws have issued conflicting decisions.

Kagan and Jackson both appeared to acknowledge the ramifications of the court’s ruling and raised concerns about the difficulties facing the lower courts when trying to weigh whether early laws are close enough to modern-day restrictions to satisfy the new standard.

“I’m a little troubled by having a history-and-traditions test that also requires some sort of culling of the history so that only certain people’s history counts. So what do we do with that? Isn’t that a flaw with respect to the test?” Jackson said, adding that Rahimi’s argument seems to call for identifying only founding-era sources that “apply to the regulation of White, Protestant men related to domestic violence.”

Kagan noted that attitudes toward and society’s understanding of domestic violence have shifted significantly over the last two centuries.

“Two hundred some years ago, the problem of domestic violence was conceived very differently. People had a different understanding of the harm. People had a different understanding of the right of government to try to prevent the harm. People had different understandings with respect to pretty much every aspect of the problem,” she said. “So if you’re looking for a ban on domestic violence, it’s not going to be there.”

The dispute has attracted input from a slew of pro-Second Amendment and gun control groups, Democratic lawmakers, and prosecutors and public defenders, who submitted friend-of-the-court briefs to the justices.

Of the parties weighing in, many of their positions have fallen along familiar lines, with pro-Second Amendment groups favoring more expansive gun rights, and Democrats and gun control organizations urging the court to allow certain firearms restrictions.

But Rahimi’s case has also led to some surprising alliances: The National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers and National Association of Federal Defenders are backing Rahimi in the case, putting them on the same side as firearms rights groups like the National Rifle Association and Gun Owners of America.

The National Association of Federal Defenders argued the Second Amendment right to bear arms is not limited to just “law-abiding, responsible” citizens, while the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers told the court that protection orders aren’t limited only to people who are not “law-abiding,” yet they would still be subject to prosecution under the disarmament law. Both groups, which represent federal public and community defenders and criminal defense attorneys, raised concerns that limiting the Second Amendment right only to those deemed to be “law-abiding” and “responsible” is unclear and could sweep too broadly.

Meanwhile, Tarrant County Criminal District Attorney Phil Sorrells, a self-described conservative Republican with endorsements from former President Donald Trump and former Texas Gov. Rick Perry, and other prosecutors throughout Texas are supporting the Biden administration and argue the Second Amendment does not protect defendants like Rahimi.

“For those who are subject to a protective order, the overwhelming evidence establishes that their firearms are not for self-defense. They are not being kept for a lawful purpose. They are weapons of intimidation, fear, and control,” Sorrells and his fellow Texas prosecutors told the court.

A decision is expected by the end of June.