This is one side of a point-counterpoint on what saved Major League Baseball following the 1994 strike. For the other side, click here.

I was away at summer camp in August of 1994 when my mother sent me a letter with the unthinkable news — Major League Baseball had gone on strike, right in the middle of the season. There would be no World Series. As an 11-year-old baseball fan with no understanding of labor disputes beyond what I gleaned at dinner table conversations between my mother and stepfather, both employment lawyers, none of it made any sense.

Many fans probably don’t remember, but Matt Williams (yes, that Matt Williams) was in the midst of a career year in 1994. He hit 33 home runs before the All-Star break, and with a leadoff shot in the top of the 2nd inning in 5-2 Giants win at Wrigley Field on Aug. 10, he had 43 through his team’s first 115 games, on pace for 61 — Roger Maris’s magical mark that had stood for more than three decades. And then it all stopped.

I wasn’t even a Giants fan, but there was something about the suspense of the six-month-long chase of one of baseball’s most storied records that transcended the normal boundaries of baseball, enveloping an entire nation and reigniting their love for the sport.

SB Nation’s Grant Brisbee plucked a particularly fitting piece of journalistic history that helps put the national scope of the home run chase into context. He references the front page of the Jackson Clarion-Ledger, from Jackson, Mississippi, on Sept. 21, 1998. The night before, McGwire had hit his 65th home run of the season, the record long since broken, 12 days earlier. Sammy Sosa was sitting on 63, his last blast having come back on the 16th.

This was not a particularly notable point in the chase that absorbed not just baseball, but the nation. And yet, the Clarion-Ledger’s sports page — in a city in a state that not only doesn’t have a Major League Baseball team, but doesn’t even touch a state that has one — led with a column and game stories from each contest. From Brisbee’s piece:

In the middle of the page, there was news about an Ole Miss offensive lineman suffering a season-ending injury. Toward the bottom, there was a little something about Cal Ripken missing his first game since 1982.

That last part is crucial, too. Whatever boost Cal Ripken’s record-setting run provided baseball in its recovery after the strike, it was nothing compared to what the ’98 home run chase did.

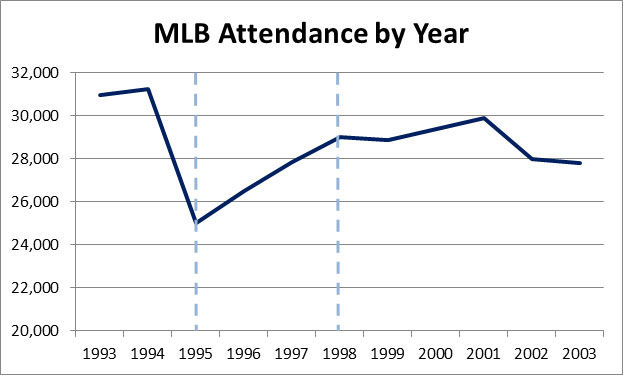

In 1994, MLB attendance had reached its all-time peak, drawing 31,256 fans per game, right up until the strike. That number cratered 20 percent the following season, to 25,021. And while the numbers climbed in each of the next three seasons, they peaked, for the time being, in 1998.

The TV ratings back it up, breaking records in 1998 before falling by the wayside in the years that followed. It makes sense — home runs make for dramatic television. Once the ball rockets off the bat, there is uncertainty as it flies through the air, the viewer at home not privy to the ball flight available in the ballpark. You take your cues from the roar of the crowd, the path of the outfielder, the fans in the bleachers, positioning themselves in anticipation. There’s the payoff as it finally lands, perhaps accompanied by fireworks, or other audiovisual displays, and the celebratory unwinding of emotion as the batter circles the bases, giving you enough time to slap high-fives and celebrate before he crosses home plate.

It’s a perfect 30-second booster shot of entertainment, quick and composed enough to fit into even the most fleeting of American attention spans.

Clearly, there was something about having two men both chasing history that resonated. One American, one Dominican; one powerful and menacing, the other lovable and full of joy. It spawned the greatest Major League Baseball ad of all time, and our love of big men mashing dingers lives to this day, 20 years later.

Living on the west coast, the only tie I had to either player was McGwire’s roots as an Oakland A, but if anything, I was still a bit bitter that he’d ended up being traded, that he was reaching for and smashing history in another city and another uniform. But I still remember where I was — in our kitchen, watching on the tiny, cable-less TV that sat on our island and was almost always tuned to sports — when he hit number 62, missed first base on the way by, and Joe Buck told us to pardon him while he stood up to applaud.

Go back and look at that photo again. After hitting No. 62, after shaking hands with the infielders as he circled the bases, McGwire embraced Sosa and lifted him in the air, the two sharing the celebration of human achievement together. While Cal Ripken’s streak was singular in its untouchability, it was also singular in its nature, necessarily achieved by one man, on his own. We can admire it from afar and congratulate him for it. But the home run chase was shared, not just between fans of the rival Cubs and Cardinals, for whom the men played, but baseball fans everywhere.

There have been plenty of revisions to the history of 1998 since, namely the after-the-fact condemnation of whatever performance-enhancing substances were boosting the long ball fiesta. After all, the top six home run seasons of all time were posted by three men — McGwire, Sosa and Barry Bonds — and all occurred between 1998 and 2001. But baseball’s attempts to wash its hands of those times have always been silly. To pretend like players weren’t popping amphetamines in the 70s, that the most competitive humans on the planet aren’t still scraping every day, even today, to find a leg up on one another to reach the pinnacle of the game, is painfully naive.

Baseball has done well to capture fan attention in the intervening years, and has been blessed with unusual parity over that stretch as well. Only the Red Sox (2004, 2007, 2013) Giants (2010, 2012, 2014), and Cardinals (2006, 2011) have won multiple titles since 2001, with Boston and the Cubs ending seemingly eternal droughts and Diamondbacks, Angels and Astros all winning their first titles. During that time, regional sports networks and digital streaming services have brought more and more of the games into homes across the country, making the sport more accessible. But nothing galvanized the entire country, enwrapped it in the daily glory of baseball, and brought it back from the dead after the strike quite like the 1998 home run chase.