WASHINGTON — The NFL season starts Thursday and Colin Kaepernick still doesn’t have a job.

I don’t really care what you think about Kaepernick as a player or a person, insofar as how it should affect his job status. Because your opinion of Kaepernick speaks far more about you than it does about him.

From the beginning of his career until last year, Kaepernick remained fairly unremarkable, by NFL quarterback standards. His numbers have been consistently middle-of-the-pack, with highs from a run to the Super Bowl in 2013 to lows like his team bottoming out last year. Through it all, his stats have remained fairly steady, neither near the top nor bottom of the league.

And yet, Kaepernick has become the litmus test for America in 2017. The case seems pretty clear that his talent is enough to get him at least a backup job somewhere, but even if Kaepernick is better than Joe Flacco, he probably isn’t measurably enough so to make much of a difference for a contender (after all, he went 1-10 for a very, very bad 49ers team last year).

So if you don’t think he should have a job at all, the question becomes: Why not?

Claiming Kaepernick is entirely undeserving of a job for football reasons shows either a wild ignorance or an intellectual dishonesty about the game. The New York Times gave space last week to a fiction writer to espouse the former. But more troubling is the work of those who really should know better going out of their way to present opinions as facts.

Last week, Sports Illustrated’s Albert Breer nearly threw his back out carrying water for the league by allowing a group of team executives and a coach to speak to him off the record so that they could trash Kaepernick without fear of public retribution. Bizarrely, all four mentioned Robert Griffin III, a once-transcendent talent now playing on the remnants of knee ligaments who has already had second and third chances to prove himself with little success. Griffin’s career numbers are worse than Kaepernick’s across the board, and he hasn’t been a dynamic runner since before his injury in 2012.

But one of the responses was insane. This unnamed executive claimed Kaepernick could never play, even back in college at the University of Nevada:

“I don’t like the guy as a player. I don’t think he can play. I didn’t think he could play at Reno, I don’t think he can play now.”

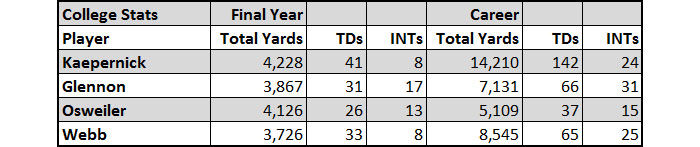

Kaepernick was a four-year starter at Nevada, where he threw for 3,022 yards and 21 touchdowns (against eight interceptions) his senior year, while running for 1,206 yards and 20 more scores. His college career can only be described as prolific. Here are his basic numbers from his final year and overall college career against some of the quarterbacks of similar age who currently have jobs.

Even at the NFL level, any way you try to bend the 2016 stats to make Kaepernick look bad, you’re inevitably left with entire swaths of players with worse numbers who are all currently on an NFL roster.

Think his 59.2 completion percentage last year was too low? Then why do Jay Cutler (59.1), Blake Bortles (58.9), Jared Goff (54.6) and Cam Newton (52.9) have not just jobs, but starting gigs in the league?

Are his 6.8 yards per pass attempt just not good enough? Don’t tell Eli Manning (6.7), Joe Flacco (6.4) or Brock Osweiler (5.8), who was so bad the Browns cut him only for the Broncos to re-sign him as a backup.

And don’t even look at Kaepernick’s 90.7 passer rating, unless you’re prepared to explain why Philip Rivers (87.9), Carson Palmer (87.2), Jameis Winston (86.1) and Carson Wentz (79.3) shouldn’t be employed, much less under center Week 1.

Even as the Niners scuffled, Kaepernick’s interception rate last year was just 1.2 percent, lower than, well, just about everyone’s, including NFL MVP Matt Ryan’s (1.3).

In a recent interview with ESPN The Magazine, Green Bay quarterback Aaron Rodgers said that it would be “ignorant” to suggest that Kaepernick’s national anthem protests haven’t had an impact on his continued lack of employment. This week, both Von Miller and Cam Newton agreed, with the latter saying he should be starting.

This is a good starting point — if you don’t believe even that there is a correlation between Kaepernick’s stance and the unwillingness of an NFL team to hire him, then you believe racial dynamics and public relations optics have nothing to do with NFL front office hiring decisions. That says a lot more about you than it does about this situation.

If you still believe he shouldn’t have a job, it stands to reason that it’s because you don’t think he should be allowed the platform to draw attention to the off-the-field issues he champions.

When sports coaches and executives say they don’t want somebody “to be a distraction,” they mean they don’t want the talk to be directed away from the game toward more real, important life issues. When sports fans say they want games to be an escape from society, they do themselves a disservice by ignoring the fact that sports are a continuous reflection of the tensions and progress of our society as a whole.

Kaepernick surely knew retribution was a possibility. His actions were done with the intent of getting noticed — otherwise, he wouldn’t have done them at all. So, is he getting blackballed for them?

Breer relies on the lazy crutch of a dictionary definition of the word “blackballed” in his piece, providing two of them, then hilariously undermining his entire column’s purpose by clearly demonstrating one of them in action. The second definition he includes — “to exclude socially, ostracize or boycott” — appears clear as day five graphs later in his own piece:

“The main thing I learned? Teams didn’t have many internal discussions about Kaepernick.”

Yes, not having discussions about a clearly competent option (one executive admitted he didn’t even bring the possibility up with ownership) would qualify as excluding socially and ostracizing.

Consider this — in 2008, a 43 year-old Barry Bonds couldn’t get a single Major League offer. He was old, yes, and probably not suited to play left field anymore, where his once stellar defense graded as below average by then. But Bonds was coming off a season in which he led the Major Leagues in on-base percentage with a preposterous .480 mark that no big leaguer with at least 200 plate appearances in a season has achieved since. He hit 28 home runs in just 477 plate appearances. His OPS+ was 169. You’re telling me that guy wouldn’t have at least been better than the first bench bat on every team in the sport?

Bonds may not have been blackballed in the sense that the owners didn’t actively collude with one another not to sign him. But he was certainly collectively ignored intentionally because of his widely perceived connection to steroids, something the sport was desperately trying to wash its hands of in the second half of last decade.

Kaepernick is getting the same treatment as Bonds, except he hasn’t even broken any rules, or done anything to damage the sport.

But it’s also not fair to act like there’s a moral imperative to sign him. On the other side of the issue came another recent overreach, an attempt to frame the argument around the ethics of a convicted serial abuser being allowed to continue to make money as a professional athlete while Kaepernick is still jobless.

Floyd Mayweather is getting an enormous payday tonight and Colin Karpernick can't get a job. Because America.

— Seth Davis (@SethDavisHoops) August 26, 2017

That comparison isn’t apt, as Mayweather isn’t dependent on team owners. But it’s also not necessary — you don’t have to look outside football to find the double-standard staring you in the face. Greg Hardy got a contract with the Cowboys after his domestic assault arrest. 49ers defensive end Ray McDonald got multiple second chances after a number of violent incidents off the field. Even Ray Lewis, who pled guilty to obstruction of justice in connection with two murders, continues to be employed — albeit by Showtime, not the league itself.

NFL teams have always been willing to look the other way in the name of squeezing a couple more wins out of the schedule. Until now.

All Kaepernick has done is try to use his platform as a visible member of our society to try to draw attention to a social issue. Whether or not NFL owners stand on the opposite side of that issue is somewhat secondary — the only point that really matters is that they don’t want Kaepernick to use that platform for their team. They don’t want to be inconvenienced by having to talk about it.

If you don’t either — even if employing Kaepernick would give you a better chance to win — what does that say about you?