July is “moon madness month” at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, said spokeswoman Lonnie Shekhtman. That’s the case both for the center’s public-facing role and in the laboratories on the massive campus in Greenbelt, Maryland: Visitors are flocking to the center in advance of the 50th anniversary of the first moon landing, on Saturday. Meanwhile, scientists are due for delivery of previously unopened Moon rocks from the six Apollo missions that reached the moon, which lasted from 1969 to 1972.

The moon landing has fallen out of the popular imagination, but at Goddard it retains a hold not only on the workers’ imaginations but on their work: Natalie Curran, a geologist born after the last moon landing, is excited about the knowledge that will come from the new rocks; meanwhile, Noah Petro, one of the scientists responsible for the orbiter circling the moon right now, is carrying on his father’s work on the first moon mission — and wants to make sure Goddard gets its share of recognition for its role in the 1969 achievement.

Both scientists spoke with WTOP about their experiences, what we learn from the moon, and why it’s important to go back.

Cream of mushroom soup?

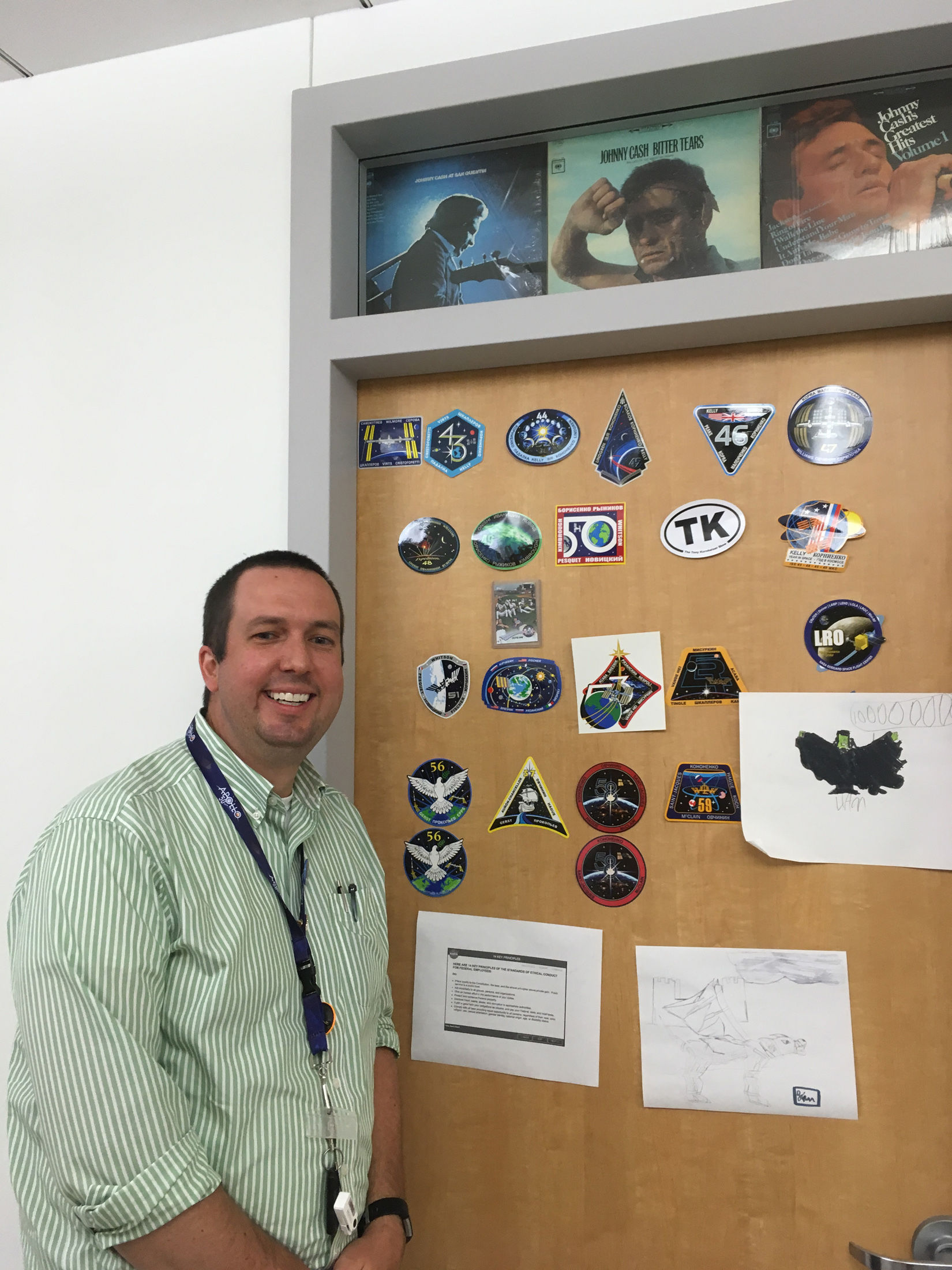

Noah Petro, 40, is a project scientist on the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, which launched in 2009 on what was supposed to be a one-year mission but has been sending back information on the moon ever since.

When he says the urge to explore — whether over the next hill or on Mars — is in humans’ DNA, it’s especially in his. His father, Dennis Petro, was an engineer with a contractor who built the spacesuits for the Apollo 11 mission that was the first to land on the moon.

“I can confidently say I wouldn’t have gotten interested in space if not for him,” Noah Petro said.

The elder Petro’s specialization was to build the backpacks that helped keep the astronauts alive on the lunar surface, and that involved starting from scratch. There had been probes on the moon before, but for the most part the people who worked on the 1969 Apollo 11 mission didn’t even know what it was they didn’t know.

Noah Petro said one of his father’s favorite stories involved the question of what would happen if an astronaut were to throw up in a spacesuit. “’How do we test that? We’re not going to put someone in there and make them throw up.’ So they took a can of cream of mushroom soup and just poured it in there. Would it clog the vents? No; it worked.”

Petro said he and his father took road trips during his childhood to ballgames and NASA centers in the U.S., and Beatles historical sites in England, and those are his three big passions today. He toured Goddard as a kid, and has a picture of himself with a Saturn V rocket in his office. When he got interested in geology in high school, he combined it with his interest in space when he went to college. He’s been with NASA for 10 years.

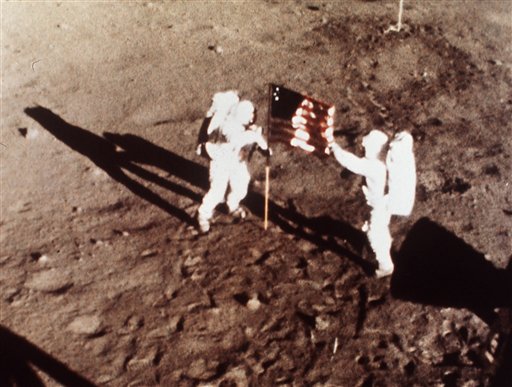

With the help of the LRO, he can see the backpacks his father helped make, sitting where Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin left them a half-century ago. “All of the engineers etched their names in the pieces of structural metal” in the backpacks, he said. “To see his handiwork left behind,” and to work with the moon samples his dad helped bring back, he said, is “one of the most rewarding things I can imagine doing in any job.”

‘It came through Greenbelt’

Noah Petro said that Cape Canaveral, in Florida, and Mission Control, in Houston, get the most attention for being the main sites on Earth for the Apollo 11 mission, but the Goddard center should get its due as well, for two important reasons.

For one, he said, Goddard was — and still is — the communications hub for the NASA program. In 1969, that meant that all messages and data sent down from the moon were sent to whatever big-enough antenna was underneath Apollo at the time of the transmission, then sent to Goddard, then on to Houston.

“When Neil Armstrong says ‘That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind,’ that communication goes down through, at the time Australia, Australia to Goddard, and then to Houston,” Petro said.

“Houston loves to take credit: The first word spoken on the moon was ‘Houston.’ Yeah, but it came through Greenbelt, Maryland.”

Petro was also proud to point out that NASA’s first geologist was based at Goddard: Paul Lowman, Petro said, was the one “who said ‘If we’re sending individuals into Earth orbit, they have to bring a camera. We need to learn about the Earth when they’re in space. It can’t just be about testing the spacecraft.’ So he worked with the astronauts on Earth observations.”

He managed the early Landsat program, which took pictures of the Earth from space, and worked with the early astronauts to get not just what Petro called “tourist pictures” of the Earth, but geologically and scientifically important images. “He was really the creator of the idea that [we should] use the Earth to understand the moon and the moon to understand the Earth.”

“I worry that the role of Goddard is forgotten,” Petro said.

‘A lazy astronaut’

Natalie Curran lays out a tray of rocks in Goddard’s Mid-Atlantic Noble Gas Research Lab and says, “in a nutshell, this is kind of the history of the solar system.”

The NASA geologist analyzes samples of moon rock, as well as meteorites and other space rocks, at NASA Goddard, and said that the delivery of new samples later this summer will be “like a new Apollo mission” for her.

The original moon missions may have faded from public memory, but the technology used on Earth to analyze the samples they brought back has advanced in leaps and bounds over the past half-century.

The computers used on the 1969 Apollo 11 Moon mission didn’t have the combined power of a smartphone, she said, and, for example, it wasn’t until 2008 that the presence of water on the moon was determined by analyzing moon rock that had been brought back by the Apollo missions decades before (and later confirmed by the LRO).

Curran and her colleagues examine the rocks to find out about the moon, which teaches them about the Earth. Because the moon is the closest planet to Earth, the bombardment both planets endured from meteors billions of years ago is similar. But on Earth, weather, erosion and movement of the tectonic plates have wiped out most of that history; on the moon, it’s all still there.

“And this kind of information has ramifications for [the question of] when did life start of Earth,” Curran said.

Curran grew up in the U.K., and humans had left the moon for the last time well before she was born. But space travel has always fascinated her. “Every time I look at an Apollo movie, or a video of a moon landing, I get goose bumps,” she said. As a kid, she wanted to be an astronaut. “That obviously didn’t happen, so now I’m kind of like a lazy astronaut: The rocks come to me.”

Going back

Petro is also part of the Artemis program, which NASA unveiled in May and seeks to return humans to the moon surface in 2024. And while you could take a been-there, done-that attitude toward the moon, he said there’s a lot of value to the mission.

For one thing, previous missions have, so to speak, barely scratched the surface of the moon: Humans have only spent about 80 hours on the moon, in six locations, and as Petro said, no one would claim to be an expert on Washington, D.C., with such limited experience. And while rovers and orbiters have been valuable, humans can bring back many more rocks from many different places. Soviet rovers on the Moon, Petro pointed out, collected about the same amount of rock in weeks as NASA astronauts gathered in days.

But Petro is also proud to cite the human element. Artemis will put the first woman on the moon, and have a more diverse crew than NASA had in 1972. And putting humans on the moon rather than rovers and probes “becomes more inspirational.”

“There’s a cool factor … but there’s also the fact that that person is normal, just like you and me. They were able to navigate their career to do something really amazing. To me, that’s very inspiring.”