Editor’s note: This is the third article in a four-part series about sharks on WTOP. Catch up and read the first article about scientists’ concerns about Shark Week shows sensationalizing the fear associated the creatures, or the second article about what great white sharks are doing off the Mid-Atlantic.

CAPE MAY, N.J. — Sharks off the region’s coast are keeping secrets, but scientists and fishermen are getting closer to cracking their code.

“We don’t know where they mate. We don’t know where they give birth. We don’t know where they migrate. And these are the animals that are the key to our children eating fish, so it’s kind of phenomenal how little we know,” Chris Fischer, founding chairman of the nonprofit group OCEARCH, told WTOP.

Fischer is confident that the full life cycle of the Atlantic great white shark will soon be understood, which is a crucial step toward working to protect great whites.

“It’s a 400-million-year-old secret, and in less than five years, we will know,” Fischer added.

He said it’s just a matter of time and money.

OCEARCH has tagged more than 20 white sharks in the Atlantic so far, and scientists say they need about 60 to be tagged in order to determine what their “normal” behavior is along the Atlantic Coast.

“We’re getting them that sample size they need so that they can publish. And that’s the whole trick, right? You can’t change the future of the ocean on a fisherman’s story. You need these peer reviewed published papers to affect policy,” Fischer said.

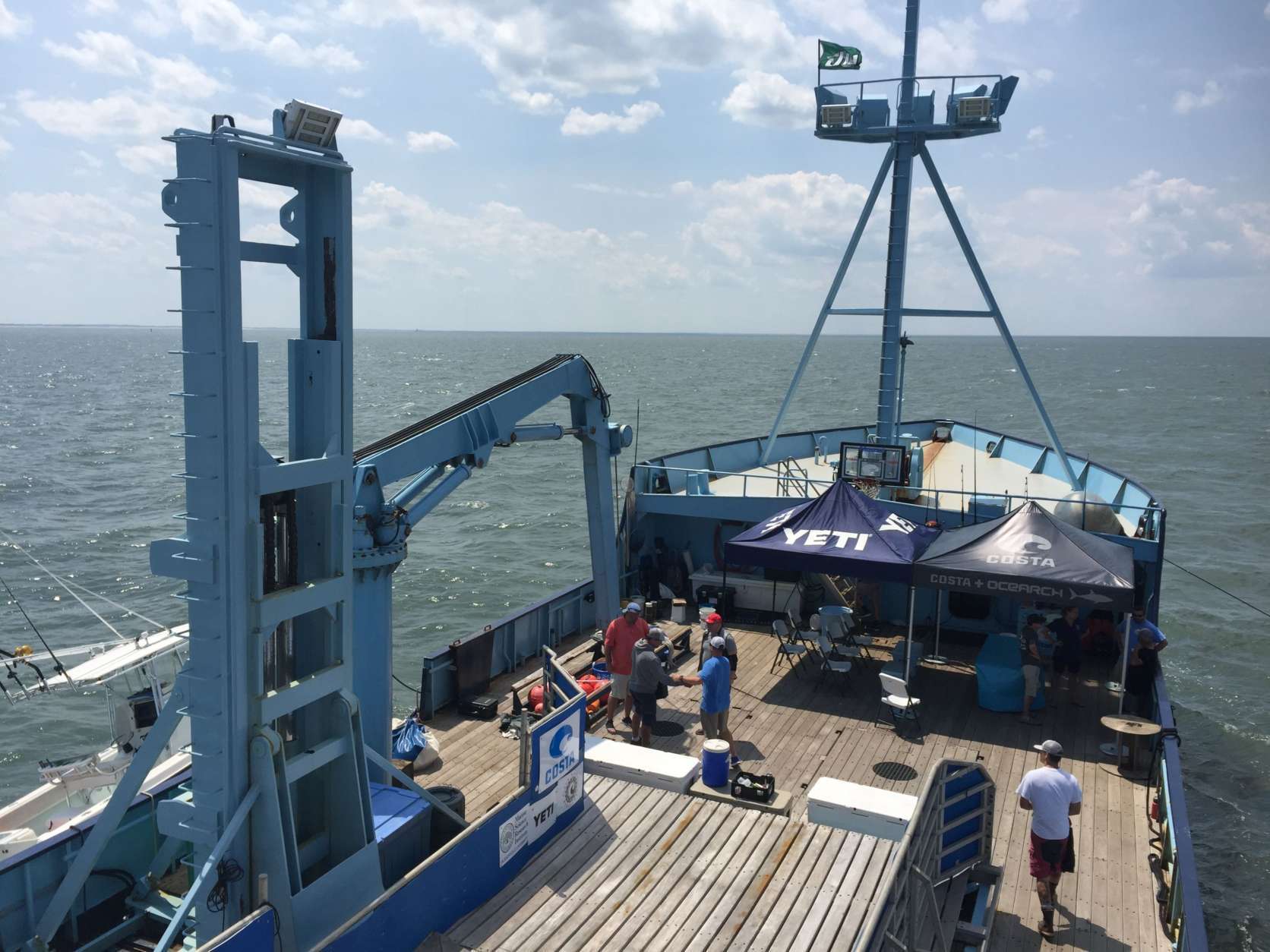

This summer, OCEARCH brought its namesake research vessel, a former crab boat, to the Mid-Atlantic.

Although it was the group’s 29th expedition, it was OCEARCH’s very first to the region.

WTOP’s Michelle Basch visited the vessel for a day as it anchored in Delaware Bay, between Delaware and New Jersey.

Among the scientists on board was Harley Newton, a veterinarian and head of aquatic health at the New York Aquarium, who is studying shark blood.

“As a human you sort of take for granted that you can go to a doctor and have them draw your blood and they know what a normal white blood cell count is and what a normal red blood cell count is. And in many shark species, we don’t even know what their normal white blood cells look like,” Newton said.

Once scientists figure out what “normal” shark blood is like, they can more easily detect when a shark is sick.

Where’s the best place to draw blood from a shark?

“There are vessels that run in a little cartilage channel that’s underneath the spinal column, and if you go back toward the tail, you can access that with a needle of the right length and gauge,” Newton said.

“A healthy shark means a healthy ocean, and a healthy ocean means a healthy planet,” said Allyson McNaughton, a veterinarian at the Virginia Aquarium and Marine Science Center.

Her job during the expedition was to use ultrasound to give every shark a body scan and examine the reproductive systems of female sharks. Hormones from females were to be checked separately.

“If we can start pairing that information and get a bigger picture of how the females are cycling, where they’re cycling, it can help sort of solve this puzzle about what they do in the different regions in the Mid-Atlantic,” McNaughton said.

Other research projects tied to the expedition involve studying shark movements in the Atlantic, comparing shark DNA and trying to find out what effect, if any, ocean pollutants are having on sharks.

As a nonprofit, OCEARCH relies on partners and other donors to keep it going. Visit the OCHEARCH website to make a donation.