WASHINGTON — Scientists have discovered a new species of dinosaur that they say was a close cousin of the iconic Tyrannosaurus rex.

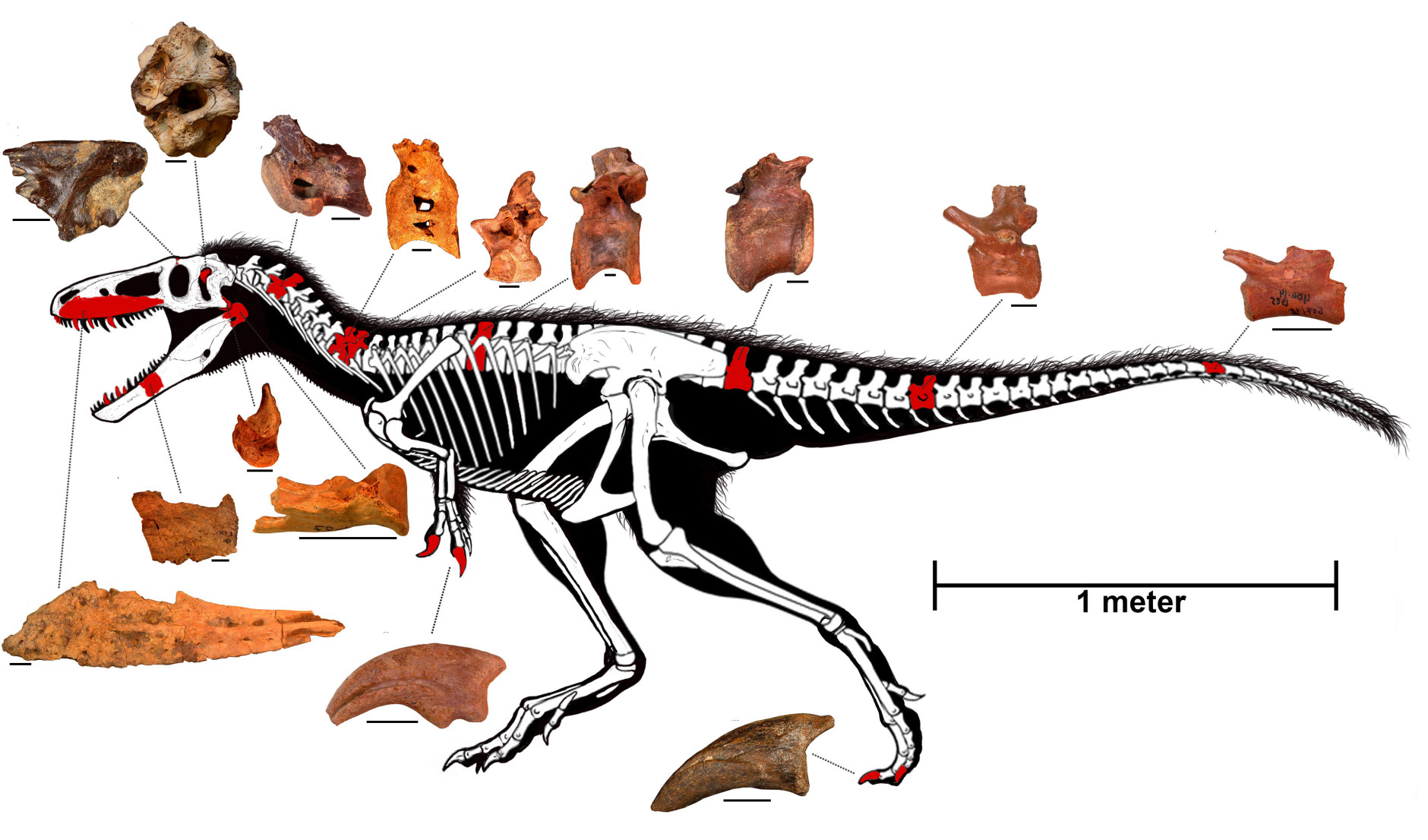

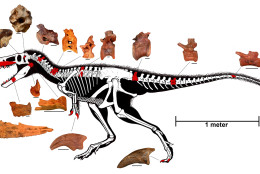

The fossils of the horse-sized dinosaur named Timurlengia euotica were recovered in Uzbekistan and found to be in the tyrannosaur family.

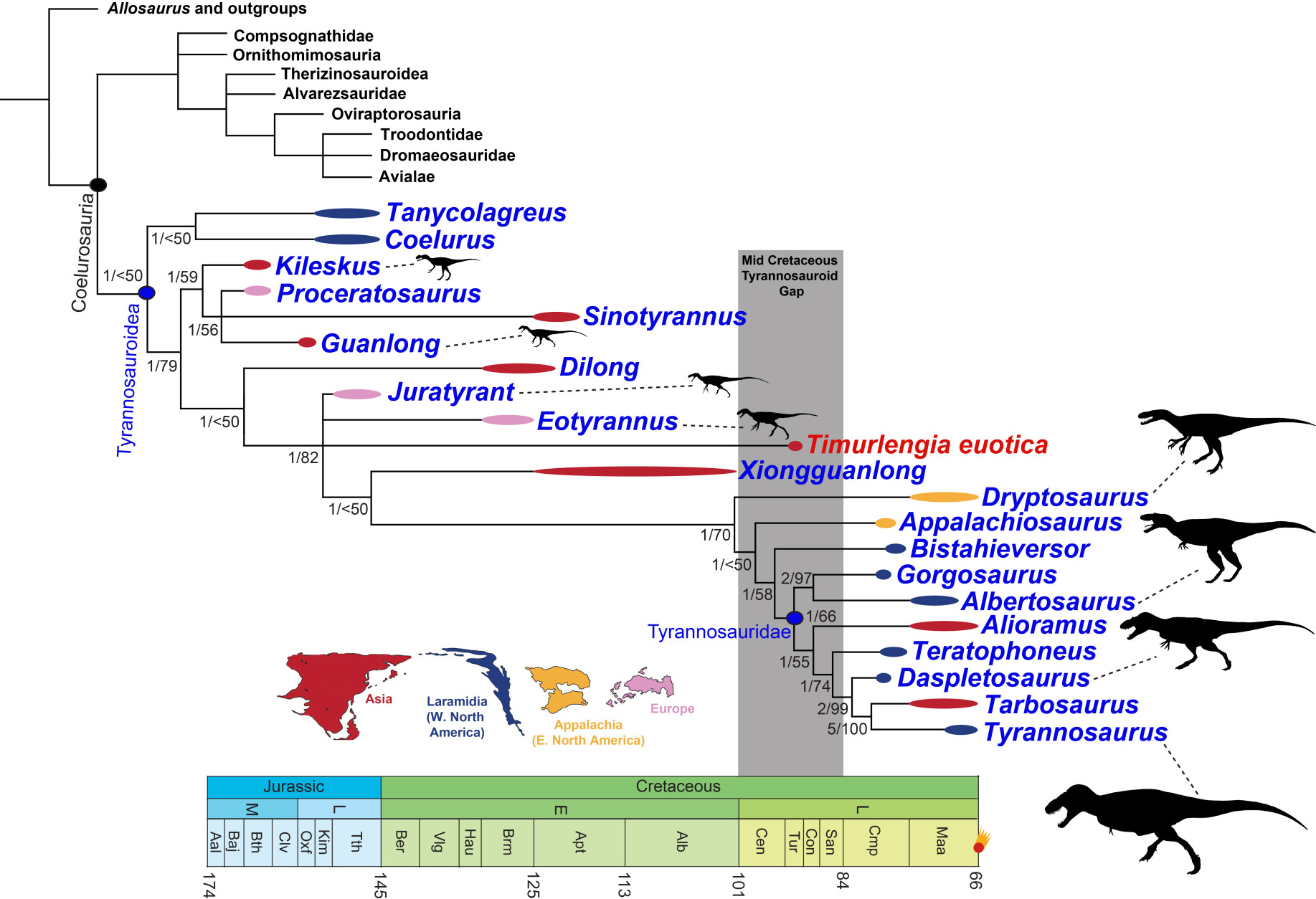

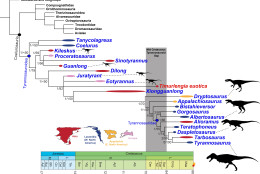

Paleontologists say this groundbreaking discovery reveals how T. rex rose to the top of the food chain and explains a 20 million-year gap in the tyrannosaur fossil record.

“How did the king get its crown? Where did T. rex come from? How does evolution produce an animal like a 40-foot long, 7-ton super predator?” asks Dr. Steve Brusatte, a University of Edinburgh paleontologist.

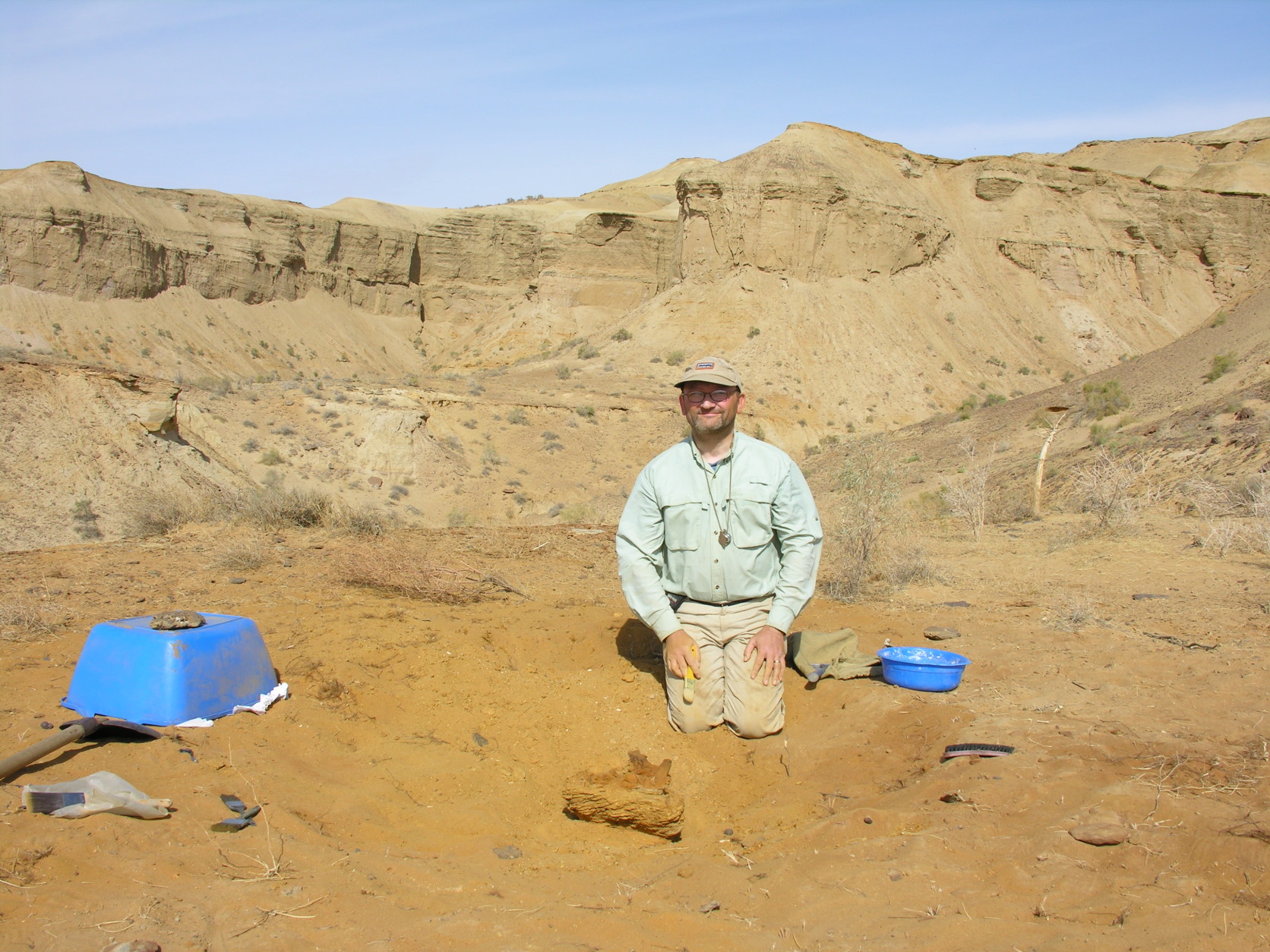

Dr. Hans Sues, chair of the Department of Paleobiology at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, and Alexander Averianov, a senior scientist at the Russian Academy of Sciences, collected the fossils during an international expedition between 1997 and 2006 in the Kyzylkum Desert in Uzbekistan.

Sues and Brusatte studied the new species using advanced imaging and released their findings on Monday.

Scientists believe T. rex was initially a very small dinosaur, about the size of a dog.

“For 80 million years, tyrannosaurs were meager, marginal animals,” Brusatte says. “Second-tier, third-tier predators living in the shadows of other types of giant predatory dinosaurs. Over the course of 70 million years, it transitioned into the powerful giant we imagine today.”

Before now, little was known about when or how the T. rex evolved; an evolutionary story that scientists have been working to decode. But now they have the key.

“This is the first tyrannosaur from anywhere in the world that fills this gap,” Brusatte says.

They believe the Timurlengia lived about 90 million years ago, right before the T. rex became the top predator. Although, Timurlengia was not an ancestor of the T. rex, the fossils of teeth, claws, vertebrae, and brain case show how the species, and ultimately the T. rex, lived.

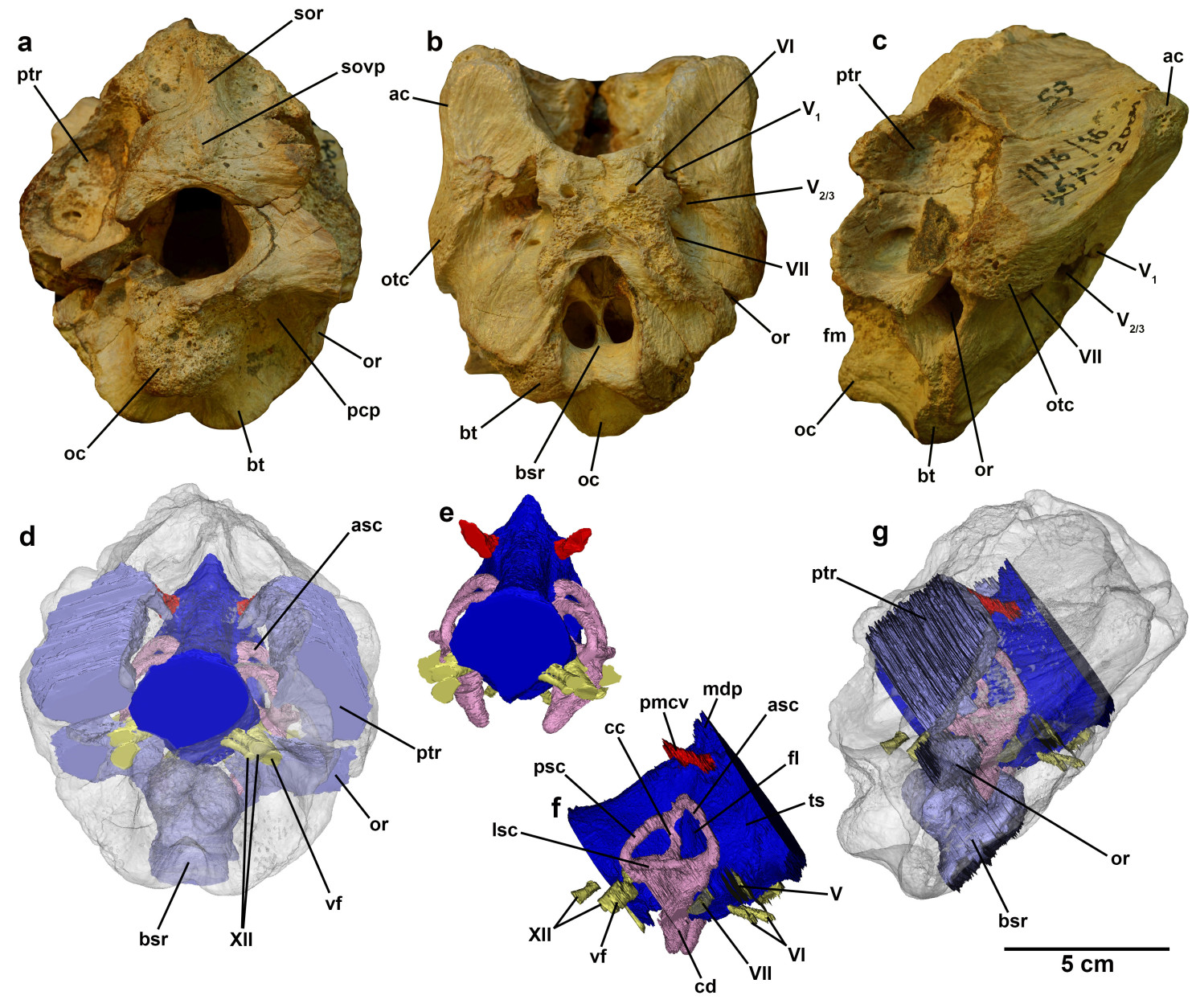

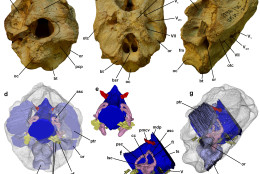

The brain case in particular was a slam-dunk for researchers. They studied the part of the skull with a custom-built CT scanner and replicated it with 3-D printers.

The scientists digitally reconstructed what the brain and ears looked like, and what they found was astonishing, they said.

Sues calls the brain case the “Rosetta Stone” that cracked the case.

They were able to determine that even though the skull was much smaller than the skull of a T. rex, its features reveal that the brain and senses were highly developed.

“Tyrannosaurs had to get smart before they got big,” Brusatte says.

The fossils also indicate that Tyrannosaurs had advanced cognitive abilities and could hear low-frequency sounds.

“We used to think that those were features of only the biggest tyrannosaurs … but now we know those sensory features actually evolved earlier,” Brusatte says.

“They’re the kind of things that may have been part of that package of ‘superpowers’ that allowed tyrannosaurs to rise to the top of the food chain when evolution presented an opportunity.”

The fossils also suggest that the T. rex grew in size suddenly, at the end of the dinosaur age.

But there are also key differences — like the teeth.

“Timurlengia had blade-like teeth. They’re almost built like the dinosaur-version of a steak knife,” Sues says.

“Nice, serrated edges. Very flat. These were teeth that would cut through meat. By comparison, the T. rex tooth basically looks like a banana on steroid. It’s a tooth that punctures through meat and bones.”

The smaller species also weighed much less — 600 pounds compared to the 7-ton T. rex.

Brusatte says advanced technology, like the 3-D printers, are painting a more complete picture of the prehistoric time.

“It’s not just dusty bones anymore. We really try to understand how these animals lived and how they evolved over time,” Brusatte says.

A spokesperson for the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History says the fossils are in the museum’s collections for research purposes but will not be available for public viewing at this time.

The new study is published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science.