This article was republished with permission from WTOP’s news partners at Maryland Matters. Sign up for Maryland Matters’ free email subscription today.

This content was republished with permission from WTOP’s news partners at Maryland Matters. Sign up for Maryland Matters’ free email subscription today.

Lawyers for the Prince George’s County Council sought to convince the state’s highest court on Friday that a controversial redistricting plan approved in November is valid, even though a lower court ruled that a procedural error was made in the plan’s adoption.

Their arguments ran into a wall of questions from members of the Court of Appeals, who were openly skeptical of the county’s defense.

A lawyer representing opponents of the plan — a high-powered attorney known for his strong ties to generations of top Maryland pols — hammered away at what he said were flaws in the council’s tactic, and his arguments drew scant pushback from the court.

The attorney, former state delegate Timothy F. Maloney, accused the council of running roughshod over the plain-language requirements of Prince George’s County’s laws and its charter.

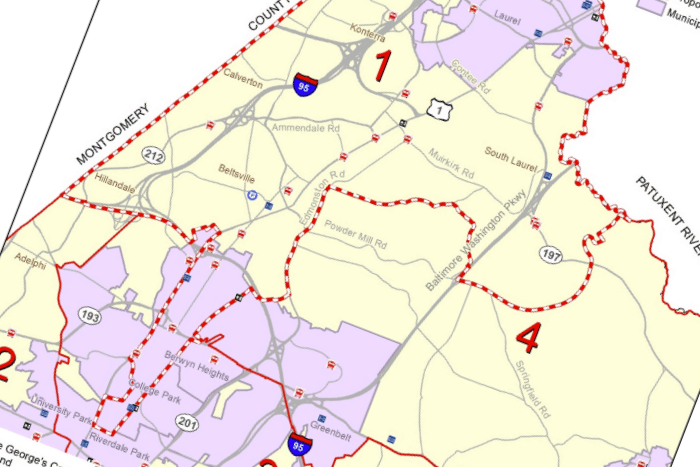

Opponents of the map the council adopted last year sued the county in circuit court. They accused six members of the council — the bare number needed to form a majority — of meeting in secret to draft a plan that protected a handful of incumbents from re-election fights by drawing potential rivals into different districts.

Despite the accusations of gerrymandering, they focused their legal attack on a narrow matter of process — the council’s use of a resolution, not a bill, to draw the new boundaries.

They prevailed in an earlier hearing. In late January, a Prince George’s County Circuit Court judge threw out the council map and ordered the county to use a plan drawn by a three-member commission, which only made minor adjustments to the current districts.

The council appealed the ruling, setting the stage for Friday’s 65-minute hearing, which was held in Annapolis and streamed online.

Maloney told the court that state law “doesn’t mean that you can use a resolution when the charter says you need a bill.”

“This really is a pretty simple question of looking at the plain language of the text,” he added.

By passing its redistricting plan as a resolution, Maloney said, the council was removing the county executive from the process because there would be no opportunity for unhappy citizens to press for a veto. He noted that all Maryland counties allow either for an executive veto or a citizen referendum.

“The framers of the charter… clearly intended for the executive to have a role,” he said.

The council’s attorney, Raj A. Kumar, and outside counsel Rosalyn E. Pugh sought to defend the way the redistricting plan was approved, even if both conceded it was “inartful.”

“Even though (the charter) focuses on ‘a law has to be passed by a bill,’ it doesn’t limit what the bill is,” Pugh said. “A rose by any other name would smell as sweet.”

Members of the appeals court began lobbing questions at the county’s attorneys just 20 seconds into their prepared remarks.

“Is there a case that you can point in our direction that is consistent with that interpretation?,” asked Judge Michele D. Hotten.

“I really wish we had that case,” Pugh replied.

The unveiling of the alternative map triggered an intense citizen outcry. Approximately 120 people spoke at an online public hearing, all opposed. One critic said the county’s appeal represented a “waste” of taxpayer funds.

After the Circuit Court ruling, Councilmember Derrick Leon Davis (D), the architect of the controversial map, predicted victory on appeal. “I am confident that we had the best (legal) advice,” he said. “We did everything that we were supposed to do.”

But Maloney mocked county claims that a 2012 change to Prince George’s law made use of a resolution permissible, noting that the council spent “less than 60 seconds” to adopt the shift.

“That is the scantest legislative history I have ever seen,” he said. “A change of this magnitude is a change of fundamental rights that requires something more than the county’s extreme stretching of the English language.”

The lawsuit against the council’s plan was filed by four county residents, two of whom support former council member Eric Olson, who launched a campaign for his old job last summer.

The Davis map included a long, finger-shaped protrusion that moved Olson from District 3, his current district, into District 1, which is represented by incumbent Thomas E. Dernoga (D). The independent commission map left him in District 3, which is currently represented by Councilmember Dannielle Glaros, who is term-limited and voted against the council’s redistricting plan.

In an interview following Friday’s hearing, Olson acknowledged that his campaign hired Maloney to argue the case before the Court of Appeals, but he declined to say how much the attorney is charging him.

The court adjourned Friday without indicating when it intends to announce its decision.