This article was republished with permission from WTOP’s news partners at Maryland Matters. Sign up for Maryland Matters’ free email subscription today.

This content was republished with permission from WTOP’s news partners at Maryland Matters. Sign up for Maryland Matters’ free email subscription today.

This is the fourth in an occasional series on Langley Park, a largely immigrant community in Prince George’s County where difficult living conditions have been made worse by COVID-19 and the accompanying economic crisis.

Days before U.S. Census takers in COVID-19 protective gear began knocking on doors Tuesday to complete the decennial survey, Census Bureau Director Steven Dillingham issued a statement that “field data collection” would end by Sept. 30, four weeks earlier than previously announced.

Workers had expected to be in the field in May, an operation upended by the COVID-19 pandemic. Now they had even less time to wrap up the operations.

Maryland is 10th among the states with 67.6% of residents responding by mail, email or on the phone, according to tallies so far for the 2020 U.S. Census.

The decennial survey, mandated in the Constitution, is used to determine legislative districts and how federal funds are allocated for hospitals, emergency services, public benefits and social services.

With the shortened schedule, there is less time to finish the once-in-a-decade job, compounding the difficulty in reaching renters, non-English speakers, and the elderly — those considered among the hardest to count and disproportionately impacted by a cut in services triggered by an undercount.

Prince George’s County Councilwoman Deni Taveras (D) has watched this scenario unfold among her constituents in Langley Park, a predominately low-income Latino community on the northern edge of Prince George’s, where many residents are undocumented and live in crowded apartments.

“Many, many are unemployed,” Taveres says. “It’s is also the epicenter for COVID, with the highest number of cases in the state,” she adds.

Langley Park response, among lowest in state

The percentage of residents who responded to the Census in three of the 22 Census tracks in Taveras’ district — two in Langley Park and one in Hyattsville — hovers around 30%, among the lowest in the state.

“It’s difficult to ask people to door-knock for the Census in a hotbed of infection, and the cutback in time is another kick in the gut,” she says. “Many people remain in the shadows, fearing rumors about a [non-existent] citizenship question [on the survey] or that undocumented people won’t be counted, a whole slew of things.”

The failure to respond would be devastating for District 2, a loss of $18,250 over 10 years for every uncounted person, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.Those monies otherwise would be allocated for schools and social

services.

“What’s sad about that, is that this is the area with the most overcrowded schools, the highest [medically] uninsured,” Taveras said. “The needs here for resources are incredible. And, it is shocking that Langley Park isn’t even meeting its 2010 numbers, in which 48% got counted.”

Despite these many challenges, Taveras has been reaching out to constituents at food distribution sites, promoting virtual phone-banking, text messaging, and working with apartment building managers to reach all the residents.

She has endorsed a recent letter from the Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments calling on the U.S. Senate, as part of the next COVID-19 relief package, to extend the 2020 Census deadline and provide “adequate funding to address continued 2020 Census challenges brought about by the pandemic.”

Shifting tactics, virtual outreach

Taveras isn’t alone in these efforts. She is on the Immigrants Count subcommittee of the 100-member Prince George’s Complete Count Committee, which coordinates Census activities with public agencies, non-profits, faith groups and citizen activists.

Among them is CASA Maryland, the largest immigrant rights group in the Mid-Atlantic. From its headquarters in Langley Park, the organization offers literacy education, worker protection, legal and health services.

CASA’s Chief Organizer Elizabeth Alex oversees CASA’s Census response. She relies on the nonprofit’s 104,000 members, who have received CASA services and remain committed to CASA’s mission.

She also has a dedicated team of 20 paid promoters who — under a $447,614 Maryland Department of Planning Census Outreach grant — started early in the year, going block by block, getting neighbors to sign pledge cards, promising to respond.

CASA promoters also hoped, before the pandemic interrupted, to canvass neighborhoods, hold house parties, stage public events, and run open clinics where people could fill out census forms online.

In March that work went virtual.

“It’s going to take every doubled effort, using every other mechanism that we can and every trusted messenger that we can find,” Alex said. “We are trying to build on the relationships we have and build new ones, people who are coming to CASA calling for help to integrate the Census message into everything and also connect it, in terms of resources that come out of a complete Census count. We’re reminding all of them about the Census in all of our relief work as they try to navigate this crazy time in terms of housing assistance, health assistance and rent

assistance.”

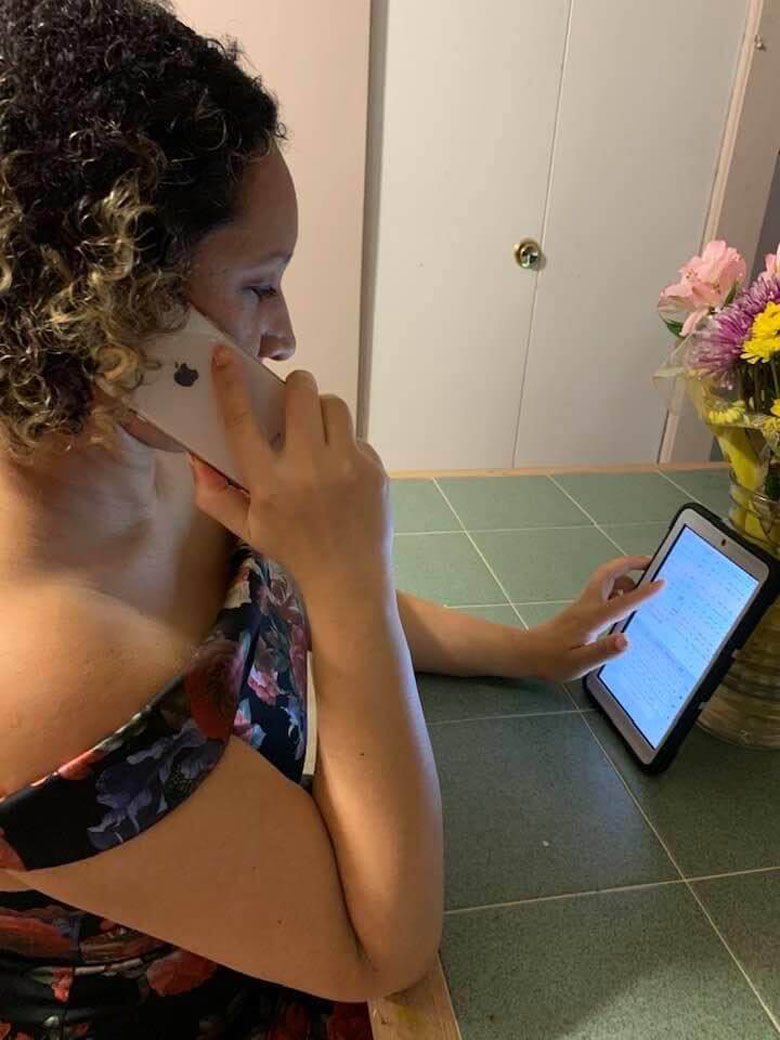

Promoters such as 41-year old Meybelin Juarez are working from home. Juarez spends six hours a day in the late afternoon and evening, working from CASA curated lists to call and send texts to remind Langley Park residents about the Census.

“It’s so important for me” says Juarez, a legal resident and single mother of five from El Salvador. “I’ve seen a lot of fear and dread in the Hispanic community from people who don’t want to fill out the Census, and I tell them it’s going to give us funds that we badly need for our schools, health clinics, better roads and transport.”

Sometimes it’s not such an easy sell, even though she tries to assure everyone she talks to that the Census is secure and confidential.

States, civil liberties groups fight to block White House Census mandate

“Sure, I’m afraid,” said CASA member Maya Ledezma, 38. “But, I was afraid to cross the border too,” referring to her entry from Mexico without documents in 2005.

Ledezma says CASA has helped her understand her political rights, and to navigate educational and social services for her family, which now includes a 12-year old daughter.

“More than anything I want to show her, that being who I am, setting an example, that I can speak out, and that [she] being a citizen, she has all the rights and can do even more.”

It is her daughter’s future that drove Ledezma’s activism and led her to join CASA campaigns for immigrant rights.

She was a vocal opponent of including a citizenship question on the 2020 Census, which the Supreme Court ruled last June violated federal law.

Late last month Ledezma rallied in Lafayette Square in Washington, D.C., challenging a presidential order that is intended to block undocumented immigrants from the Census count.

Ledezma says filling out the decennial survey is a civic responsibility like voting, and she reassured protest onlookers that she was in it for the long haul.

“We’re continuing to support [immigrants]. We are in the fight, without papers and without fear,” she said.

Alex, who began CASA’s groundwork for a complete count nearly two years ago, said she feels a shift in momentum.

“People engaged in this work are seeing through the threats to eliminate immigrant voices and using it as fuel to get a complete count from everyone.”

CASA and other civil liberties groups filed suit against the order that would keep undocumented residents from being counted, as did a coalition of 21 attorneys general, including Maryland Attorney General Brian E. Frosh (D).

“We want to make sure that President Trump can’t erase this country’s millions of hard-working immigrants and cripple the regions that have welcomed them as neighbors,” says CASA Executive Director Gustavo Torres, referring to his neighbors in Langley Park, who stand to lose the most in an undercount.

Rosanne Skirble is a freelance writer in Silver Spring.

Click here to read the first story in our Langley Park series.

Click here to read the second story in our Langley Park series.

Click here to read the third story in our Langley Park Series.