WASHINGTON — When stories of child sexual abuse top the headlines, it shines a disturbing spotlight on the issue.

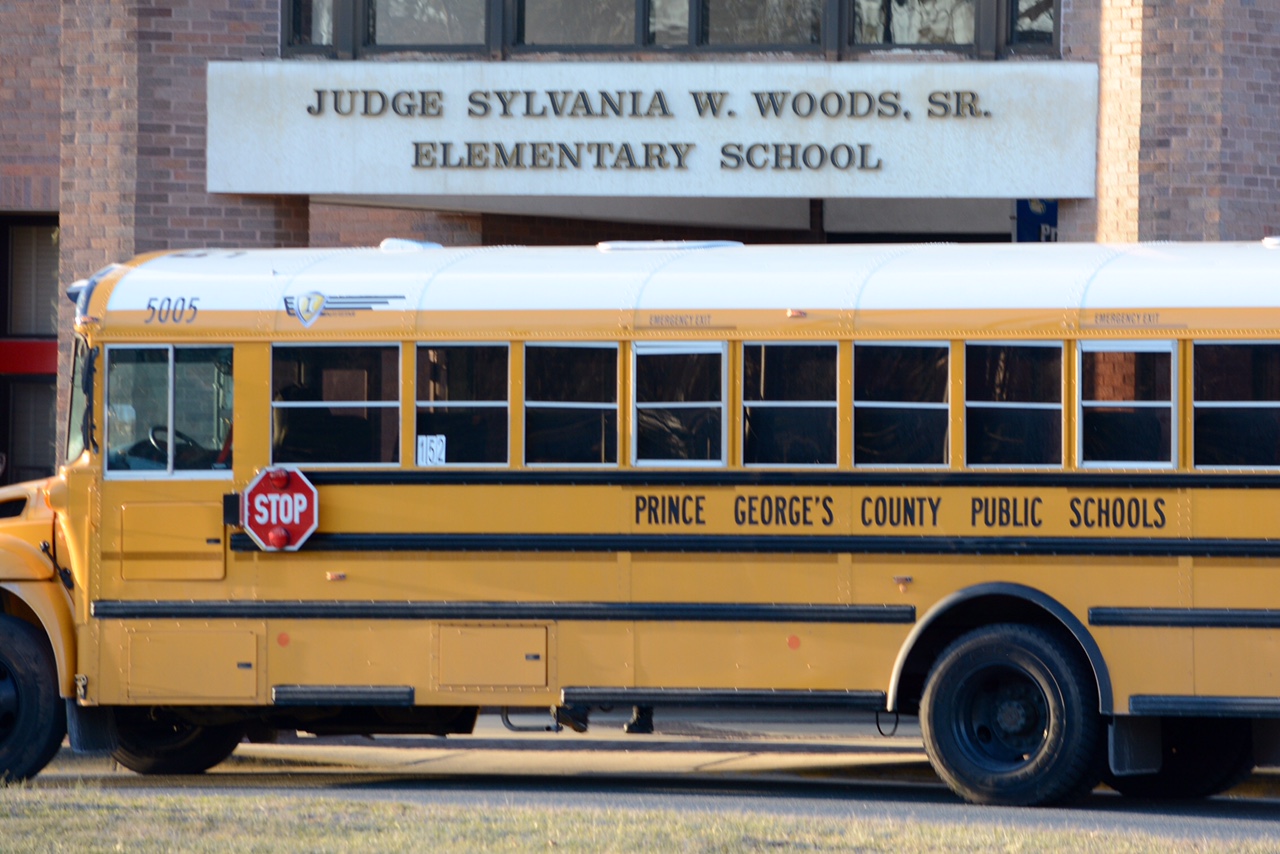

Deonte Carraway, a 22-year-old school volunteer, recently pleaded not guilty to federal child pornography charges in a case that so far includes close to a dozen children between the ages of 9 and 12. Although the subject may be uncomfortable and even sickening to most adults, it may be a good time to talk to your child about sexual abuse.

WTOP’s Stephanie Gaines-Bryant talked to psychologist Dr. Kimberly Brooks, of Dr. Kimberly Brooks and Associates, about how to have that conversation in an age appropriate way.

“With a very young child, it’s more of a conversation about their body and their body parts. And, keeping that conversation using anatomically correct terms so that they’re comfortable with the discussion about their body in general and that they’re comfortable with talking about specific body parts using correct language,” says Brooks. “As children get older, the more casual and playfully you can talk about it. With teenagers it can come up when you’re driving to games or driving to school. It can come up as a result of songs that you hear on the radio and sharing mistakes and decisions that you’ve made. ”

Brooks says don’t just have the “big talk,” but instead, have regular family time to keep the lines of communication open.

“I’m a big proponent of having regular family time, so that it’s not a set aside time that you sit down and discuss difficult issues. But, regularly at dinner time, family game night, family movie night … whatever it is … there’s a regular time for everyone to sit down, come together and talk about all kinds of things – not anything in particular but if this happens to come up, this is the venue for it because we have family time.”

Also, talk to your children about social media and technology.

“I would say if you’re not willing to do your homework and put the parental control apps on your phone, check his or her phone occasionally. If you’re not willing to do that then it’s probably not a good time for them to have that device, whether it’s a cellphone or an iPad,” says Brooks.

She advises that parents put some groundwork in place that makes children vulnerable.

“Because again, it’s not the apps … It’s not the devices that makes them vulnerable. Vulnerable kids gravitate toward the things that cause them harm,” Brooks says.