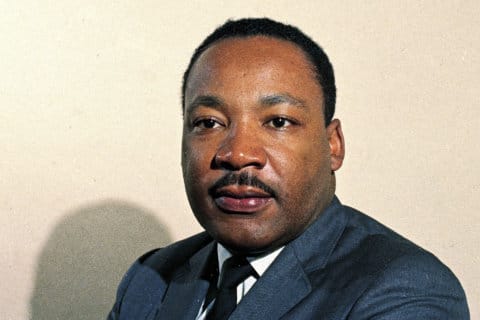

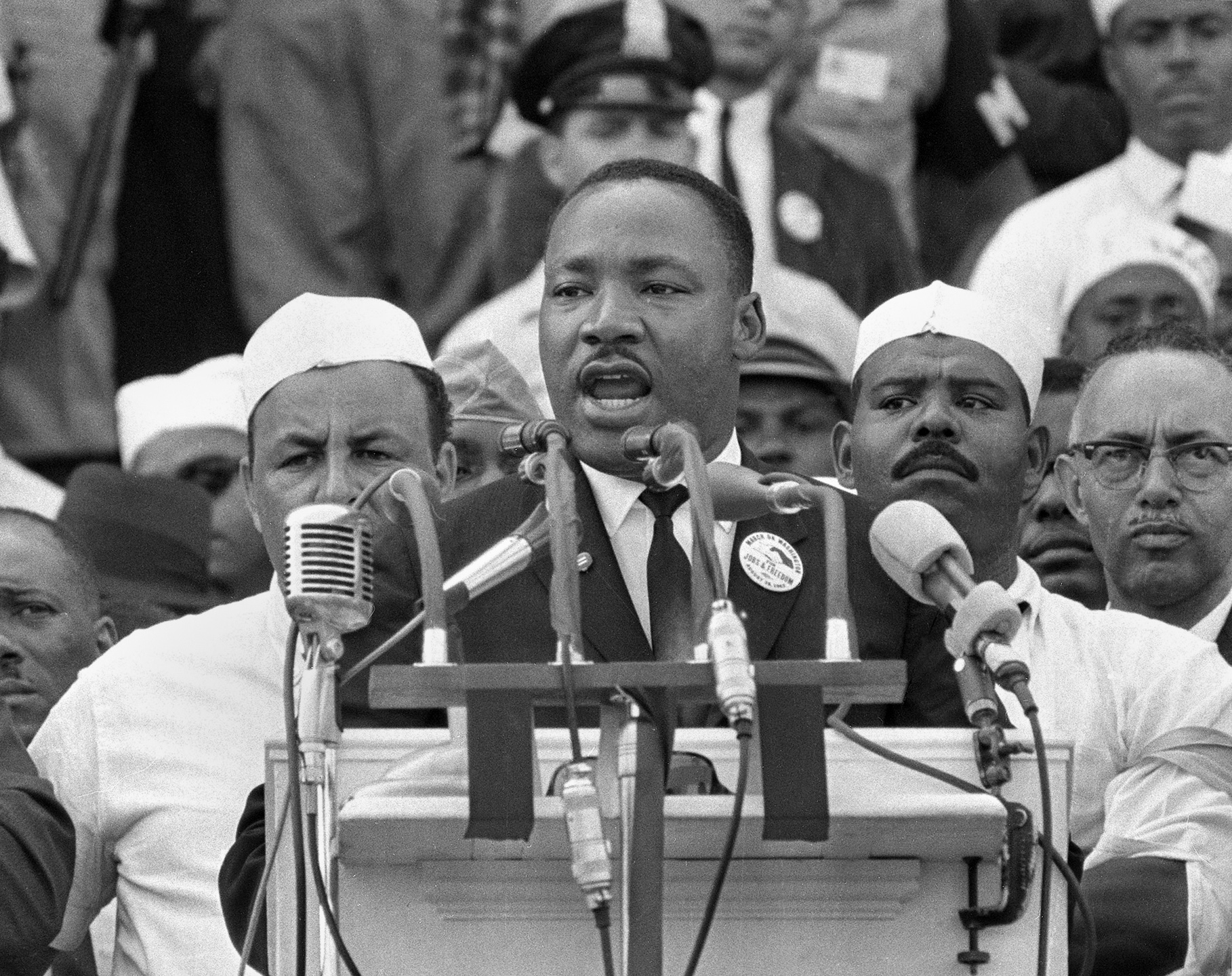

WASHINGTON — Civil rights leader and Nobel Prize winner Martin Luther King Jr. died almost 50 years ago. He would have been 87 years old on Jan. 15. One of my mom’s friends, who witnessed King’s inspirational 1963 “I Have a Dream” speech on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, recently told her two kids about her participation. They were dutifully impressed. Then the younger one asked: “Mom, did you know Abraham Lincoln too?”

This is the challenge we parents face in making an icon, one who was a living and breathing force to many of us, relevant to our children today.

Here are some ways to do so, no matter how old your kids are, every day of the year.

- Share lesser known facts about King that are more relevant and memorable to children than the dates and milestones they memorize in school. For instance: his name was originally Michael, but when he was two, his father changed it to Martin. He often got in trouble with his parents as a child, causing him to jump off the roof of his house when he was 12. He got a C in public speaking, even though today he is remembered as one of America’s finest orators. He spent his honeymoon in a funeral parlor, because a friend offered it to him to use for free. He had four children with his wife Coretta, and when he died at age 39, his oldest was only 12.

- Make MLK local. Find out a few facts about a place that is meaningful to your kids, where King made a speech or held an important sit-in, and use that local history to make King relevant to them. In D.C. where I live, this is easy — but King held marches, rallies and activist meetings around the U.S. and the world. In addition to extensive travel in Georgia, Alabama and Tennessee, Martin Luther King went to India, Berlin, Oslo and elsewhere. An easy trick: find out if your town has one of the 902 streets in the U.S. named for him.

- Tell them your own memories about King’s legacy. I describe to my kids the day in second grade that my public elementary school was officially “integrated” with a bus of African American children from another neighborhood — and how hard it was for these children, but how much we all benefited from the change. Valerie, the new girl who sat next to me, became one of my closest friends, yet we never visited each other’s houses. I ask my kids to imagine how awkward, controversial and hopeful the “desegregation” or “forced busing” program was for young children and their families. How would they feel if one day they were required to ride a bus to a different school, completely outside of their choosing, in a potentially hostile neighborhood they may never have been to before?

- Talk about how little our society has changed since the 1960s, the busiest years of King’s activism. “A state trooper pointed the gun, but he did not act alone,” King said at a funeral in 1965. “He was murdered by the brutality of every sheriff who practices lawlessness in the name of law. He was murdered by the irresponsibility of every politician, from governors on down, who has fed his constituents the stale bread of hatred and the spoiled meat of racism.” King could have been speaking at a funeral caused by recent police brutality in Baltimore, Chicago or Ferguson.

- Talk about how much our society has changed since King’s death. We have 44 black members of Congress and our first black president (although he received 30 death threats a day when he first became president). Many cities, including Washington and Atlanta, are now majority African American and every aspect of our society, from sports to education to entertainment, is more integrated than it was during King’s life. Use the movie “Selma,” or other movies that naturally get kids pondering how we’ve overcome or failed to overcome complex issues of race in America, such as “Remember the Titans” or “The Blind Side.”

Before giving in to cynicism, thinking that watching a movie, visiting a statue, or talking about a memory won’t make any difference in ending the racism we all still live with today, here’s what Martin Luther King cautioned: “Our lives begin to end the day we become silent about things that matter.”

It’s up to us and the next generation — our children — to continue King’s courageous work.

Leslie Morgan Steiner is a contributing writer to WTOP.com.