You may think of ventilators as the last line of defense for patients who are critically ill with COVID-19. But that’s not always the case. Next-level life support exists for some of the sickest patients struggling to recover from the novel coronavirus.

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, or ECMO, replaces the function of the heart and lungs. ECMO is helping some COVID-19 patients for whom standard treatments have failed and a mechanical ventilator alone is not enough to safely support their breathing.

Similar to heart-lung machines often used during open-heart surgery, ECMO works by pumping and supplying oxygen to the patient’s blood from outside his or her body. By contrast, patients sometimes stay on ECMO for days on end to give their bodies a chance to recover from life-threatening conditions now including COVID-19.

A new study shows how these extremely ill patients are faring on ECMO so far. Conducted in 213 hospitals across 26 countries, the study provides an estimate of the risk of dying with ECMO support for life-threateningly ill patients with COVID-19.

That mortality risk is similar to what prior studies have found for adults who were life-threateningly ill for other conditions, says Dr. Ryan Barbaro, lead study author and a clinical assistant professor in pediatric critical care medicine at the University of Michigan.

Among critically ill COVID-19 patients in worsening condition, who had failed mechanical ventilator support and other intensive therapies, slightly less than 40% died after being placed on ECMO.

“This means that outcomes for patients with COVID-19 who are sick enough to require ECMO support might be about the same as for similar sick patients who became ill for other reasons, such as bacterial pneumonia or influenza,” says Barbaro, who is also a pediatric intensivist and researcher at Michigan Medicine’s Child Health Evaluation and Research Center.

The study, which analyzed outcomes on 1,035 patients with confirmed COVID-19, appeared in the Oct. 10 issue of Lancet. The patients, ages 16 or older, had ECMO support during the period between Jan. 16 and May 1.

After the 90-day study period, 6% of patients with COVID-19 on ECMO remained hospitalized and 37% died. Another 40% of COVID-19 patients who received ECMO were discharged to home, an acute or long-term rehab center or another unspecified location, and 17% were discharged to another hospital.

“While we cannot be certain what would happen to these patients without ECMO, doctors usually choose to use ECMO because they fear the ventilator might be failing to support their breathing or because they are worried the patients might die without ECMO support,” Barbaro says.

Barbaro is chair of the registry committee for the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization, the international nonprofit group whose data was used in the study. The ELSO registry of facilities lists nearly 950 ECMO centers worldwide, with about one-third located in the U.S.

[See: What Are the Symptoms of Coronavirus?]

What Is ECMO?

The extracorporeal in ECMO means “outside the body.” The membrane is the gas-exchange device that takes over the work of the patient’s lungs. Oxygenation is treatment to increase oxygen supply to the lungs and to blood circulation. ECMO removes carbon dioxide waste from the blood and returns oxygen-rich blood back to the body.

“ECMO is akin to dialysis for the lungs — in that the same way that dialysis cleans the blood of toxins when the kidneys have failed, ECMO removes the carbon dioxide from the blood to support the body when the lungs have failed,” says Dr. Cara Agerstrand, director of the medical ECMO program and an associate professor of medicine at Columbia University Irving Medical Center, and a co-author of the Lancet study.

Columbia has ECMO programs for both adults and pediatric patients. Up to 15 patients may be receiving ECMO at a time at New York-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center, Agerstrand says.

Patients Treated With ECMO

Adults and children are treated with ECMO for severe heart or lung conditions including:

— Heart failure.

— High blood pressure in the lungs, or pulmonary hypertensive crisis.

— Massive blood clot in the lungs, or pulmonary embolism.

— Patients awaiting a transplant or ventricular assist device placement.

— Acute respiratory distress syndrome, or ARDS.

— Severe pneumonia.

— Life-threatening asthma, or status asthmaticus.

— Severe influenza, or flu.

— Severe COVID-19.

“Since the beginning of the pandemic, we’ve been treating patients with severe COVID-19 with ECMO support for both respiratory and cardiac failure,” Agerstrand says. “With COVID-19, the vast majority of patients are presenting with lung problems — severe forms of acute respiratory distress syndrome.”

ARDS is a progressive, life-threatening condition in which patients develop severe shortness of breath. Many require ventilator support and other intensive treatments. Currently, Agerstrand says, the use of ECMO for ARDS, whether it’s due to COVID-19 pneumonia or regular pneumonia, is reserved for someone who has failed conventional, standard-of-care approaches to mechanical ventilation.

In addition, some patients with COVID-19 may have already gone through a trial of proning, a stomach-lying positioning technique used to improve breathing for people with severe ARDS.

[SEE: What to Say to Friends or Family Members Who Hesitate to Wear a Mask.]

ECMO Circuit

How does ECMO appear to family members? “It is a metal box, often located at the end of the bed, with blood spinning through a pump and large blood-filled (cannulas) attached to their loved one,” says professor Carol Hodgson, head of the division of clinical trials and cohort studies in the School of Public Health and Preventive Medicine at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia.

ECMO is made up of five major components:

— Cannulas. These plastic tubes are inserted in large blood vessels, such as the femoral artery at the groin or the external jugular vein of the neck.

— Oxygenator. The drainage cannula sends blood from the patient to the oxygenator. This artificial lung, or membrane, removes carbon dioxide from the blood and adds oxygen, all from outside the body.

— Pump. Acting as the heart would, the rotating pump sends the oxygen-rich blood back to the patient via the return cannula.

— Blender. The blender provides fresh oxygen to the oxygenator.

— Control panel. The operator, or perfusionist, adjusts ECMO settings.

When a Ventilator Isn’t Enough

Most COVID-19 patients placed on ECMO are already on a ventilator. ECMO is added when the ventilator alone is not meeting the patient’s needs.

“Normally, the lung takes on oxygen and removes CO2,” Barbaro explains. “But when the ventilator is no longer able to do that support, or the pressure itself can cause harm,” that’s when ECMO may help, he says.

Ongoing pressure on the lungs from ventilator support can cause injury to the lung, Barbaro says. “In extreme circumstances, the pressure that the ventilator intervention (exerts) can cause a pneumothorax — meaning air can escape from the lung. It can burst the lung and escape into the chest,” he says. “And that’s a problem.”

With ECMO doing the work exchanging oxygen and carbon dioxide, less ventilator pressure is needed. That, Barbaro says, allows the patient’s body to heal while giving the medical team an opportunity to use medications and other treatment to promote that healing.

How Patients Experience ECMO

Patients are sedated as they’re connected to the ECMO machine. Afterward, sedation or pain medicine helps keep them comfortable. Because most ECMO patients are already on a ventilator, and because they’re so sick, their movement is already quite limited.

Patients who go on ECMO are often placed in a medically induced coma and kept immobilized, says Hodgson, who is also deputy director of the Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care-Research Center and a specialist ICU physiotherapist at the Alfred Hospital in Melbourne.

As patients waken, they are moved very carefully so as not to dislodge the cannulas, Hodgson says. “In expert ECMO centers, some patients who are awake may be allowed to mobilize — even stand and walk while the ECMO is running,” she adds.

“Typically, patients with COVID-19 are told that they need to be deeply sedated, at least when ECMO is initiated,” Agerstrand says. “If someone is doing well and clinically improving, we try to lighten their sedation and allow them to be awake and following commands, if at all possible.”

Who Receives ECMO?

ECMO is generally used in patients who are younger than 65 and who were previously healthy, Hodgson says: “People who are older, frail or have other medical conditions do not respond as well.”

The decision to put a patient on ECMO is painstaking, with assistance from the ELSO COVID-19 Guidelines. The potential benefits and hazards are carefully weighed and discussed with patients and family members. But it’s an emotionally charged decision to consider about a loved one who is critically ill in an “incredibly difficult circumstance,” Barbaro notes.

It’s frightening for family members to realize that even rigorous critical care including a ventilator isn’t enough and options are narrowing, Barbaro says: “They’re using a support system for which there’s not something beyond ECMO to provide.” It can be difficult for families to absorb all the new information they’re given around the decision, but they’re well aware it’s a momentous one.

In a 2003 study including feedback from parents of children treated with ECMO for severe ARDS, parents talked about making the decision to use the highly technical therapy. “Although parents theoretically had the choice to consent to ECMO, many felt that there was not a real choice to make given the starkness of the options: survival or death,” wrote authors of the study published in the journal Pediatric Critical Care Medicine.

For physicians, Barbaro says, building trust with families in this situation is essential “by being able to communicate with them what you’re doing and why you’re doing it, and answering questions and being honest about the unknown.”

ECMO Risks

ECMO treatment has major risks, including:

— The large ECMO cannulas, or tubes, can cause nerve or blood vessel damage.

— Bleeding can occur as patients are often being managed with anti-clotting medication to prevent clotting within the ECMO circuit.

— Infection can result whenever tubes are placed in the body.

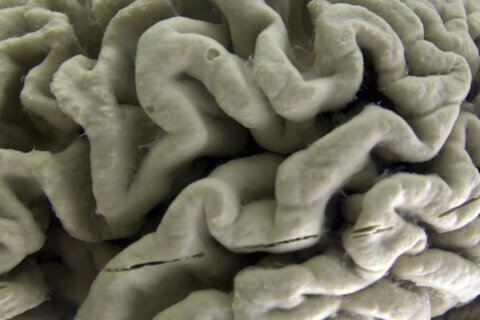

“In the most severe form, bleeding can include intracranial hemorrhage,” or bleeding within the skull or brain, Hodgson notes.

[See: Home Remedies Not to Try for COVID-19.]

Extensive resources are used in the care of severely ill COVID-19 (or other) patients on ECMO. “It is one of the most expensive therapies provided in the ICU — and should be considered in patients who have a reversible disease and are expected to recover,” Hodgson says.

Already rigorous ICU care is now layered with ECMO-management needs, Barbara notes. Multidisciplinary team members — along with family members — for patients on ECMO may include:

— ECMO attending physician.

— Critical care physician.

— Pulmonary specialist.

— Cardiac specialist.

— Nurse practitioner.

— Critical care bedside nurses.

— Respiratory therapist.

— Pharmacist.

— Physical and occupation therapists.

— Psychology, psychiatry and spiritual care providers.

— Child life specialist for pediatric patients.

Weaning Off ECMO

As patients with COVID-19 show signs of recovery, they may be gradually weaned off ECMO. “We tend to think of weaning being appropriate once the underlying illness that put them on ECMO in the first place is getting better,” Agerstrand says. “Typically, patients who need ECMO support for respiratory failure require it between seven to 14 days.”

In the Lancet study, the average time that patients needed ECMO for COVID-19-related respiratory failure was 13 days, Agerstrand says. It usually takes several days to wean patients, she says. However, she adds, some patients recover quickly and are weaned within 24 hours or so.

It’s important to understand the pandemic’s toll on previously health people, Agerstrand says. “Of patients in the Lancet study who received ECMO for COVID-19-related ARDS — who were the sickest of the sick patients with respiratory failure from COVID — nearly one-third of them had no comorbidities,” she points out. “They were relatively young, they had no underlying medical conditions and they were previously totally healthy.”

Although it’s true that older patients with underlying conditions are more likely to get severely ill from COVID-19, Agerstrand says, “We see so many young, previously healthy 20-, 30-, 40-year-olds coming in with such severe COVID that ECMO is the only option they have as a lifesaving therapy.”

More from U.S. News

Ways to Boost Your Immune System

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE): Definition and Examples

What Is ECMO for COVID-19? originally appeared on usnews.com