BALTIMORE, Md. — It’s nearly Valentine’s Day. And for humans, love is in the air. But it’s a good time to examine how love is in the air for crabs, too, and how their mating affects a Maryland industry.

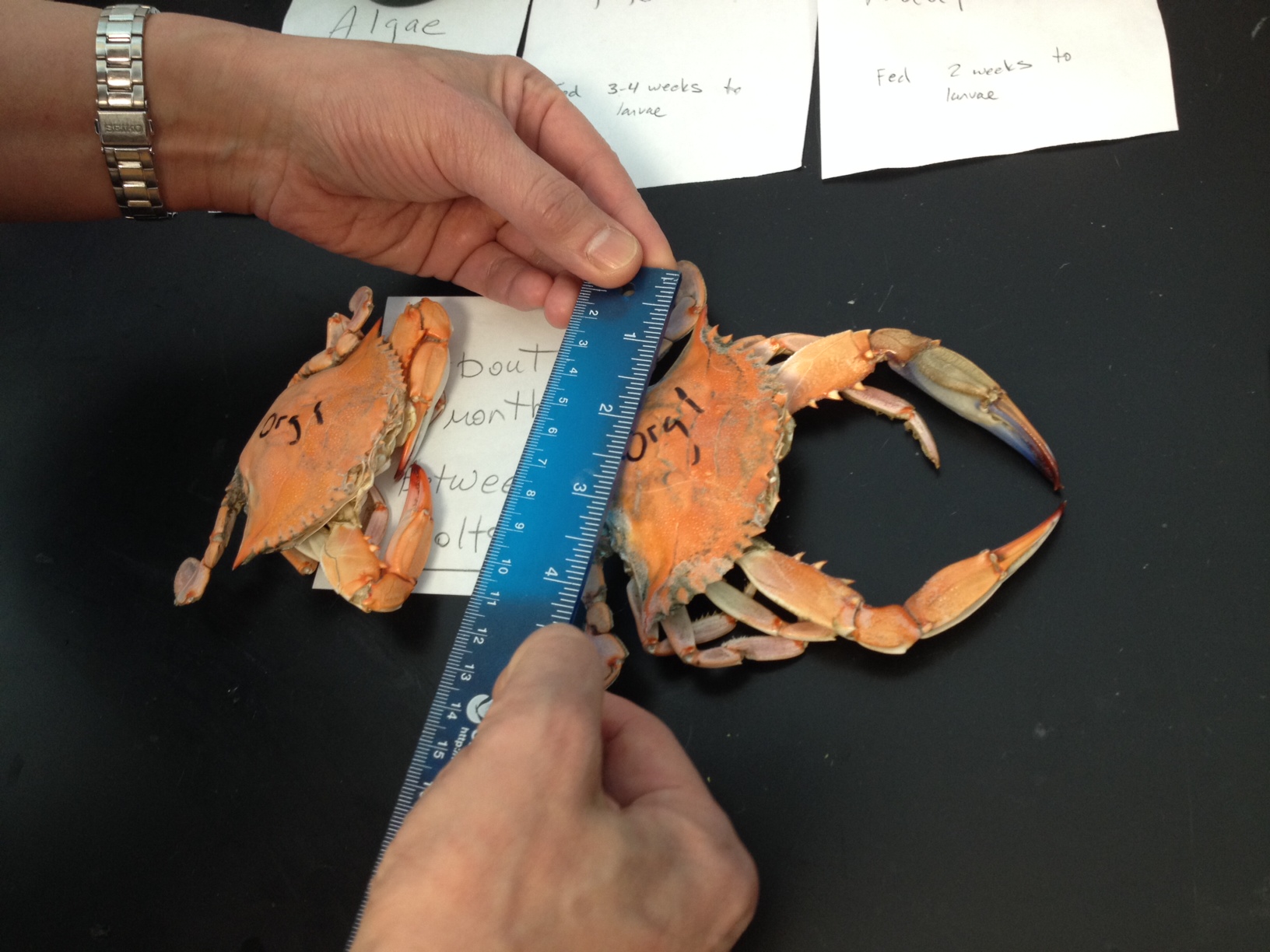

For blue crabs, it’s all about the pheromones in the water. And for female crabs looking for mates, size really does matter.

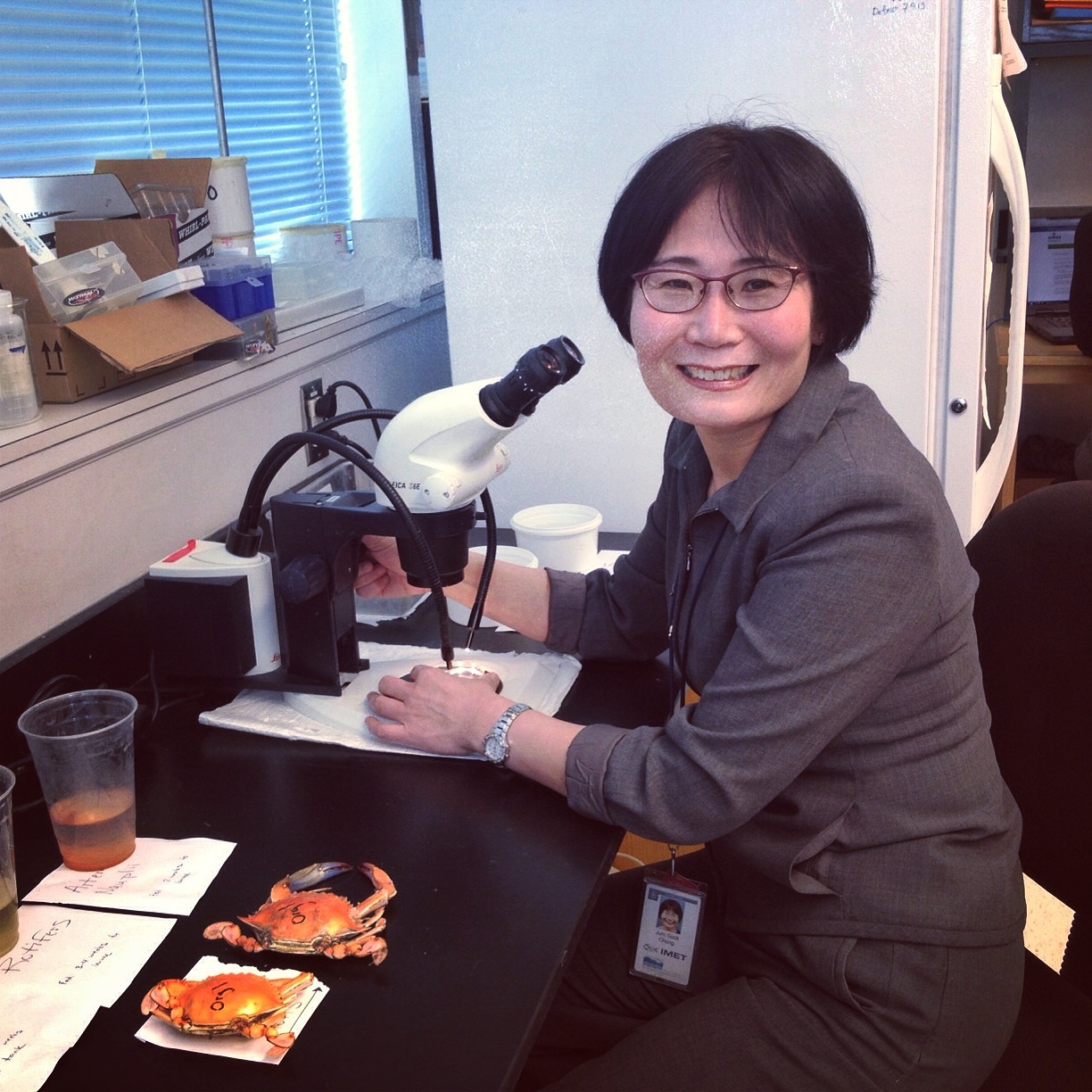

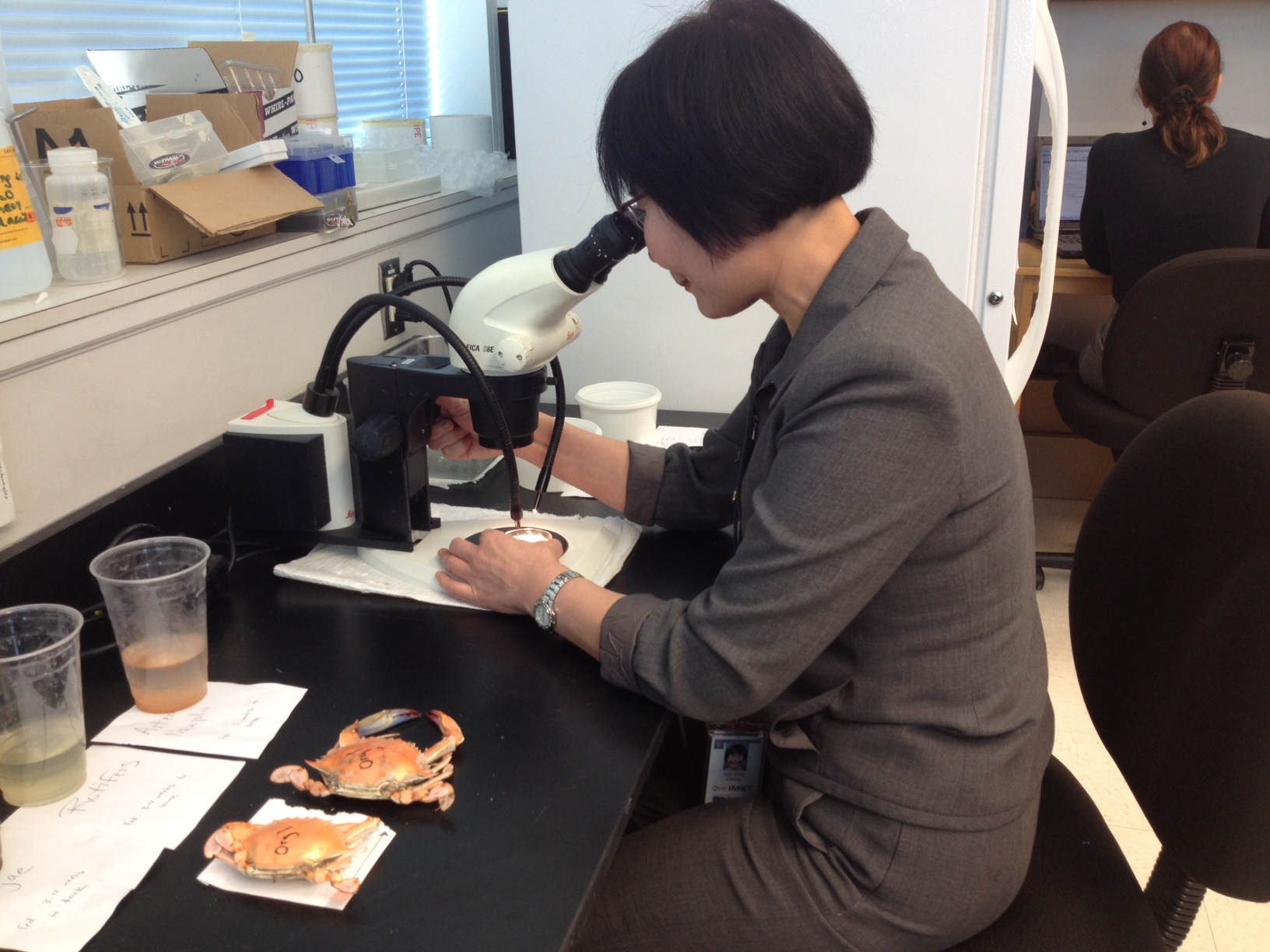

Sook Chung, an associate professor at the Institute of Marine and Environmental Technology at the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science, explains that a larger male may produce more sperm, and that’s critical to the female, who gets just one chance to mate.

“That’s it — just once,” says Chung, who adds it’s important female crabs find a large male who can produce lots of sperm to fertilize her eggs, ensuring that she can produce as many tiny crabs as possible.

Chung helps study the intimate lives of blue crabs, which has real implications for Maryland’s Chesapeake Bay and the outlook for the state’s watermen. Chung says knowing that females depend on finding larger males could have implications for policies on harvesting crabs. Knowing the timing of the mating cycle also can have an impact on harvesting.

The crab courtship begins long before the male shows up. Chung’s research has revealed that hormones that allow the female to develop into a breeding adult are housed in her eyes. And how she “sees” her potential mate matters, too. When the male comes along to do his dance for her, Chung says, “she crouches down, and her eyes are level” — that is, her eye stalks are held level. The male, meanwhile stands on tiptoe, waving his limbs around to impress her.

“He has to show that he is a good partner,” Chung says. The message, she says has to be “I’m big, and I’m something!”

Timing is everything. When the female crab sends out a signal by excreting pheromones into the water, the males show up. The one who impresses her the most will get the chance to mate. But Chung says he’s got a very narrow window: The female has to mate when she’s ready to shed her hard shell. Then it’s up to the male to clutch her in a protective grasp, keeping her safe in her vulnerable state, and mate while she’s in her soft-shell state.

Soon, she’ll have a new hard shell, and won’t mate again. But she will carry the male’s sperm to fertilize her eggs. She may produce millions of tiny larvae, all depending on the amount of sperm she’s collected.

Chung says knowing how pheromones affect crab behavior could have valuable results for commercial watermen.

Crabs will feed on each other, and anyone who’s ever watched crabs in a bucket can tell you how they will attack and damage each other. But during mating, when the female’s released pheromones, male crabs are actually quite gentle and won’t eat. Chung says releasing sex pheromones into water when crabs are shipped could get them to calm down, resulting in a catch that’s intact and more appealing to buyers.

Chung didn’t start her career by focusing on marine life. She originally studied insects, but made the change to marine studies after discussions with colleagues. And she found a connection with the blue crab: She’s a native of South Korea and her first name is Sook. When she came to Maryland to study crabs, she learned that watermen call male crabs “Jimmies” and females “Sooks.”

It’s a coincidence that amuses her.

WTOP’s Kate Ryan contributed to this report. Follow @WTOP on Twitter and on the WTOP Facebook page.