Stephanie Gaines-Bryant, wtop.com

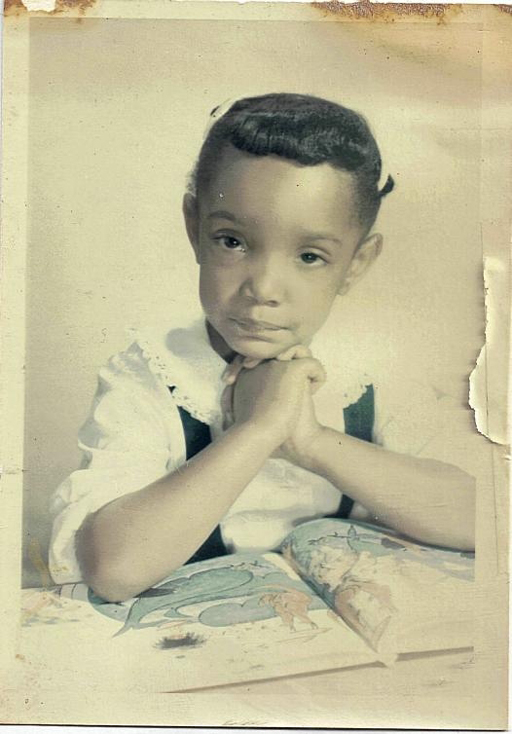

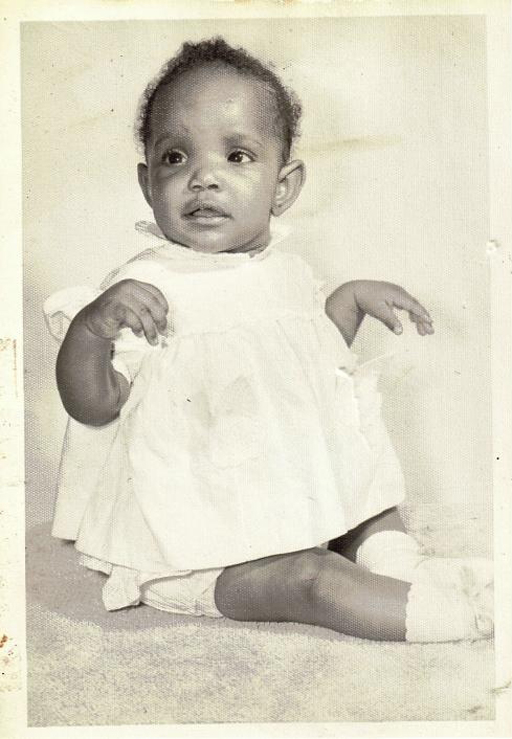

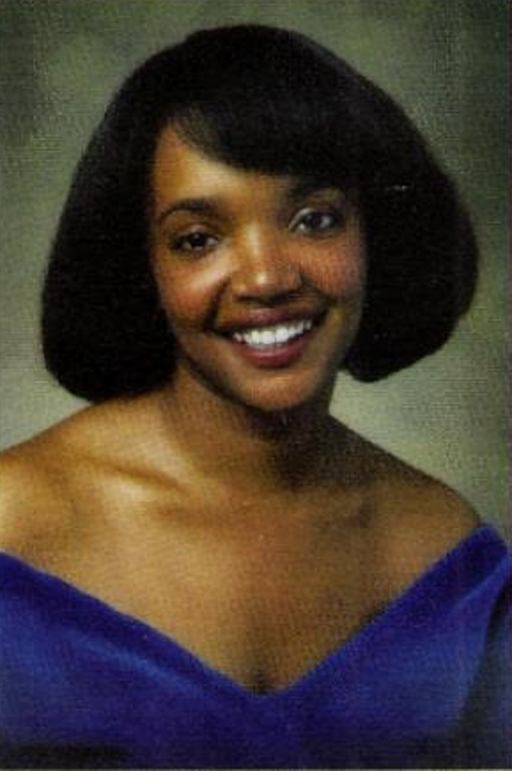

WASHINGTON – At 5 years old, I made history in my hometown of Vauxhall, N.J. My siblings and I were among the first black children to enter the all-white Franklin Elementary School. I was one of the first black kindergarteners to enter the school. There were no National Guard troops there to escort us into the school, no angry whites shouting racial epithets, just me and Momma walking hand in hand into the red brick building.

It was September 1966. The country was in the grips of the civil rights movement. But the movement was just beginning to spread in other directions. Dr. Martin Luther King began speaking out about the Vietnam War. Black youth began taking a more militant stance. And the summer had been ablaze with riots in Chicago, Omaha, Cleveland and Dayton.

My father was taking a stand of his own by insisting his children enroll in Franklin Elementary School opposed to Jefferson Elementary where most of the black children in our community attended school. It was no secret that Jefferson was run down, and the school books were inferior. While black community leaders wanted to wait for the government to help enforce integration laws, Pops refused to wait any longer. He said the time was now.

Pops was a product, or victim, of the Union Township Public School system in New Jersey. He said it was a system that set black students up for failure. Blacks and whites attended separate schools until high school. Once blacks joined the white students at Union High School, many of them, including my father, were unable to compete and ended up dropping out of school. As a result, Pops joined the military at age 17. After a three-year stint in the Army, he returned to New Jersey, where he met and married my mother.

I was the sixth of seven children born to Fletcher and Louise Gaines. The couple owned a small landscaping business, and my mom worked as a nurse’s aide at a local hospital. We lived with my grandmother in the same house my father was born in back in 1929, the same year Dr. King was born. He was a fan of Dr. King’s non- violence movement, while my older siblings leaned toward a more militant strategy.

“Burn Baby Burn,” a phrase coined by African-American D.J. Magnificent Montague, quickly became the rallying cry for black youth following the Watts Riots in Los Angeles. Pops often said that was the craziest thing he’d ever heard. He’d say in his common sense voice, “Instead of going to the white neighborhood, they burn down their own homes. Then, the fools ain’t got no place to live.” Little did we know that the fires of discontent were about to spread closer to our home than we ever imagined. Newark, N.J. went up in flames the following summer.

I don’t remember any one day that school year that stood out more than another. What I do remember is feeling painfully alone and different all day, every day. The pain especially stung on the days when we played “Ring Around the Rosy,” and no one wanted to hold my hand because they thought my color would rub off on them. They would ask me questions like, “Do you have a tail under your dress because we heard Negroes have tails?” They asked me about the texture of my hair, the thickness of my lips. But the question most frequently asked — “Do you tan?”

I also dreaded school trips where students were required to partner with one another. No one ever wanted to be my partner, so the teacher would assign someone to me. Partnering with me was seen by the other students as a form of punishment. “Children you better behave or you’ll have to sit with Stephanie,” my teacher said. The mere threat would bring some of the children to tears, while others would quickly straighten up.

I usually ended up with *Sarah Flowers. The kids called her “The Pee-Pee Girl.” At 5 years old, she still wet her pants. But Sarah was the best dressed girl in the class. She always looked like she just stepped out of the pages of a Montgomery Ward catalog. She wore colorful jumpers with matching tights and shiny patent leather shoes, but by the end of most days her outfit would be soaked. Her mother came in almost every day with a change of clothes. The first time Mrs. Flowers walked through the classroom door, there was no doubt she was Sarah’s mom. Sarah was a mini version of Mrs. Flowers. They both had skin the color of Ivory soap, and noses that so dominated their faces, there was little room left for their lips and marble shaped blue eyes. Sarah’s walnut colored hair was cut like the little Dutch boy, while her mother wore a flip with bangs.

In addition to the wetting, Sarah suffered from what I now suspect were allergies. Her nose released what appeared to be a never-ending stream of snot. She sniffed and wiped and sniffed all day. There weren’t enough tissues in the room to keep up with her runny nose. And when there were no tissues available, Sarah used whatever was closest to her — construction paper, lined paper, scissors, crayons, but mostly the back of her hand. I dreaded holding her snotty little hands. They felt like slimy wet cotton balls, but I was too afraid to complain. I didn’t want to do or say anything that might draw more attention. Being the only Negro in the classroom was quite enough. So, Sarah and I were stuck together that year