▶ Watch Video: The movement to expand Idaho’s border into Oregon

Mike McCarter knows his American history almost as well as he knows his Bible. His family has lived and worshipped in Oregon for four generations. “The only time I lived out of the state was during the Vietnam War when I was in the military,” he said.

But his Oregon may not be the Oregon you’re thinking of, the one with the misty rugged coastline, pinot noir wineries, and its loyally Blue politics.

McCarter lives in the town of La Pine, in the state’s rural and more sparsely populated part – the Red side of Oregon.

“It’s almost like the Grand Canyon goes right along the Cascade Range,” he told correspondent Lee Cowan. “It is a big divide.”

What that means politically, he says, is that the Blue part of Western Oregon always outweighs the Eastern part’s Red. “In talking to a legislator over in the Portland area, I said, ‘The legislature doesn’t listen to our people, our representatives over here.’ He said, ‘Whoa whoa whoa, stop, Mike. We hear what they’re staying. We just out-vote you.'”

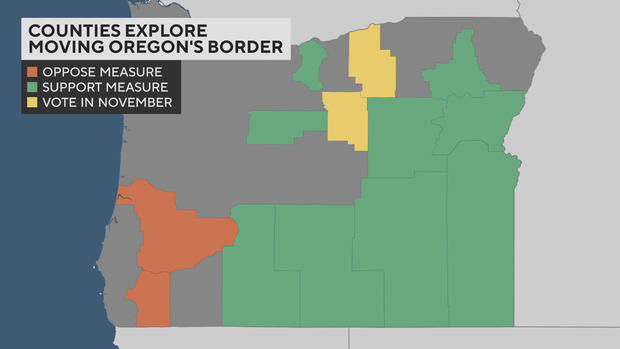

So, McCarter decided to look for greener pastures – or in this case, at least ones a little more red. He’s leading a movement called Move Oregon’s Border, which seeks to push the Blue bits into a smaller but still populous state of Oregon, and then taking the rural Red bits and making them part of a bigger Idaho.

In a state dominated by progressive politics, some Oregonians east of the Cascade Mountains want to move the border so that their counties become part of Idaho, a more conservative state that more closely aligns with their values.

In a state dominated by progressive politics, some Oregonians east of the Cascade Mountains want to move the border so that their counties become part of Idaho, a more conservative state that more closely aligns with their values.

CBS News

Cowan asked, “How much land are we talking, roughly?”

“About 63% of Oregon’s land,” McCarter replied. “A big chunk.”

Sandie Gilson owns a real estate business in rural John Day, Oregon, which is closer to Boise than it is Portland in virtually every way. She told Cowan, “When you have a government that won’t listen to the opposition, or take into account those of us that live out here, then we have no government representation.”

“Is it a political difference? Is it a cultural difference?”

“It’s all of the above,” Gilson said. “They won’t hear our concerns, they don’t understand our lifestyle.”

She’s been going door-to-door in support of the Greater Idaho Movement, and she says she’s found fertile ground. Of the 11 counties that have put it to a vote, nine have endorsed it, and it’s on the ballot in two more counties this November.

Next month voters in Morrow and Wheeler Counties in eastern Oregon will decide on ballot measures in support of becoming part of Idaho.

Next month voters in Morrow and Wheeler Counties in eastern Oregon will decide on ballot measures in support of becoming part of Idaho.

CBS News

Some who voted against it worry that it could discourage political discourse. It might even set a dangerous precedent for other states. Others, though, say moving a state’s borders seem almost logistically impossible. So, really, what’s the point?

Cowan asked Gilson, “Are you optimistic that you think you have a chance?”

“I look at it like the American Revolution was a big hurdle to make, and they did it,” she replied.

Richard Kreitner, author of the book “Break It Up: Secession, Division, and the Secret History of America’s Imperfect Union,” says it’s hardly a new idea: “I don’t think that we should act like state lines are written in stone. We should look at them and say, ‘Does this actually make sense?’

Little, Brown

“Secession has always been there. Catholics lived in Maryland, debtors lived in Georgia, you know, Puritans lived in New England. They were kind of separate to begin with. And that’s why they wanted nothing to do with one another.”

“So, it’s really woven into our DNA?” asked Cowan.

“Absolutely. There’s nothing sacred about Oregon. There’s nothing sacred about Delaware or my native New Jersey, in my opinion. You know, these are just kind of inherited forms.”

You might be asking right about now, instead of going through all the trouble to move the border, why not just move across it?

A self-described Libertarian, Derek Williams moved his family to Idaho from the suburbs of Portland. “When you feel, like, that you don’t have a voice, you make a decision,” he said. “It was extremely difficult to leave family and friends. A lot of tears were shed.”

In the town of Eagle, Idaho, he said he found other political refugees, a conservative majority, and no discontent or disconnect anymore. “You come here and you’re like, ‘Oh my gosh, I had no idea that it could be this way.’ And you feel accepted, and appreciated for who you are.”

Mike McCarter knows the concept of majority rule can certainly be messy. What he’s worried about is when, he says, it teeters on tyranny. That’s when something has to be done. And the best people to decide just how, he says, are the voter themselves.

“We’re all sending the same message to Oregon’s leadership, that you’ve got a problem in eastern Oregon,” he said. “If we get done with this, and it doesn’t come about the way we want it, at least we did it the right way, so be proud of that.”

For more info:

- GreaterIdaho.org

- “Break It Up: Secession, Division, and the Secret History of America’s Imperfect Union” by Richard Kreitner (Little, Brown and Co.), in Hardcover, eBook and Audio formats, available via Amazon, Barnes & Noble and Indiebound

- richardkreitner.com

Story produced by Michelle Kessel. Editor: Remington Korper.