▶ Watch Video: Top tips on what you should or should not recycle

Americans, asked to imagine they were an item in a recycling bin, had to describe what happens to them next. In the range of responses to a March poll, 15% of those polled took the pessimistic route and said, “I go to a landfill.”

The pessimists have a fair chance being right. According to trade groups, about 25% of the things we try to recycle end up in landfills.

With plastic packaging, the issue is particularly acute. The U.S. generates more plastic waste than any other country, but hasn’t managed to create the well-functioning recycling systems some other nations enjoy. Only about 30% of the readily recyclable rigid bottles and jugs that are consumed in the U.S. are successfully recycled, according to the Environmental Protection Agency’s latest data from 2018.

- 10 Earth Day facts that might surprise you

- 5 ways to make your home more Earth-friendly

- What happened to acid rain? How the environmental movement won — and could again

- How we make and buy clothes is hurting the planet. Here’s a solution.

“How is it that we can put a man or a woman on the moon, and yet we still don’t know how to recycle properly?” asked Mitch Hedlund, executive director of the nonprofit Recycle Across America.

There are a few knotty problems to sort out before packaging waste can be recycled well in this country, and local governments and non-profits are invested in the solutions because plastic has a long life — about 400 years — and scientists are finding that what we throw out has a way of coming back to us. When plastic goes into landfills it winds up polluting the oceans and the microplastics can find their way into our water supplies and our bodies. We physically consume about a credit card’s worth of plastic per week, studies suggest.

Disposal is often cheaper

There’s a patchwork of recycling services across the country, and many Americans live in cities without convenient curbside options. Half a decade ago, China accepted and paid for an estimated 70% of the plastic people recycled in the U.S., but at the beginning of 2018 they stopped importing much of the world’s recycling. When the demand from China collapsed, hundreds of cities could not afford to collect and sort. As CBS News reported in the summer of 2018, Fort Worth, Texas went from earning $1 million recycling before China’s import ban to seeing losses of more than $1 million after.

Since then, more domestic remanufacturers have come online to take on the supply of used plastics, but demand still hasn’t met supply everywhere in the country. States like Oregon and Maine are beginning to adopt the policies in place in much of the European Union and Canada to make their recycling programs affordable again, said Sarah Nichols, sustainability director for Natural Resources Council of Maine. In 2021, Maine led the way and passed a law that will require packaging manufacturers — instead of taxpayers — to pay to turn their plastic bottles back into bottles again. The law should go into effect before the end of the decade.

“When that happens, there’s funding available for recycling, which is a huge reason why recycling is not working because it’s cheaper to dispose,” said Nichols.

Nichols says she is working with other states to try to turn the new trend into a wave, and some like Colorado are currently considering adopting versions of these policies, known as extended producer responsibility programs.

Recycling symbols can be confusing

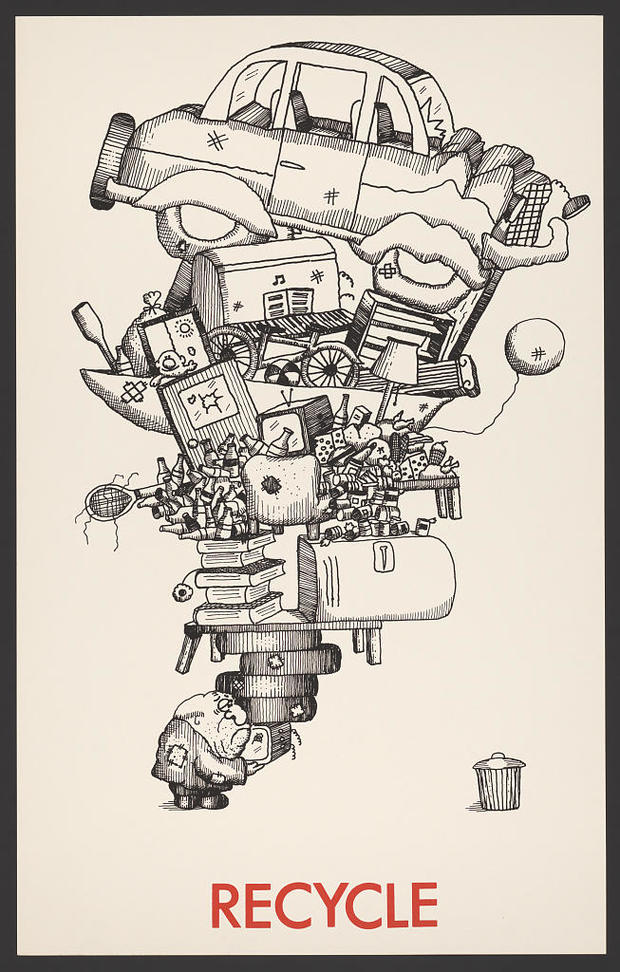

A recycling poster from the 1970s, from the Library of Congress

A recycling poster from the 1970s, from the Library of Congress

Library of Congress;LOC DSC

In the 1970s, a packaging company paid the college student who won their design contest a few thousand dollars for the chasing arrow symbol that’s now ubiquitous on the bottom of packages. Consumers have come to think of it as the national symbol of recycling. But the chasing arrow icon is far from a foolproof green light that the package is recyclable in your area, according to experts.

“You’ll see containers that will do the chasing arrow symbol. And the material is not recyclable on the curbside. It’s not recyclable anywhere,” said Dereth Glance, deputy commissioner for Environmental Remediation and Materials Management of New York.

Strawberry containers and yogurt containers might have the chasing arrow signs, but they aren’t recyclable in most places, said Hedlund, who advocates for legislation that would standardize labels on recycling bins.

“The packaging industry is making it sound like you’re in control of how you’re supposed to recycle plastics when in all reality, most plastics that you get, that we all get, are not recyclable today in the U.S. or in most of the world,” Hedlund said.

In most of country, consumers should only be throwing the rigid #1 or #2 plastic containers in their recycling bins — these include clear, plastic containers like Coca-Cola bottles and opaque containers like milk jugs and shampoo bottles, according to Hedlund.

When in doubt, throw it out, Hedlund advises. But people willing to research can find the full list of plastic waste that can be recovered in their area through their local department of public works.

If American consumers only tried to save what was accepted in their area, recycled plastic would be less labor-intensive and more competitive with new, or virgin, plastic.

“We’ve all learned how to drive properly once in our lives, and we all look at the standard road signs and know exactly what to do instinctively. And that’s where recycling can be,” Hedlund said.

Sorting equipment isn’t up to snuff

Most of the material recovery facilities around today were designed in the 1990s, according to the EPA, but our waste stream has changed since then.

“Rapid innovation in plastics and packaging has resulted in new types of materials that continue to pose challenges to current recycling infrastructure,” said Nena Shaw, acting director of EPA’s Resource Conservation and Sustainability Division.

The flimsier plastic that you use to seal a tray of leftovers and that manufacturers use to package paper towels gums up the works pretty easily. It’s a constant headache for material sorters, according to Glance.

“If you put that in your bin, that’s going to stop recycling flat. It jams up the machines. It just doesn’t work,” Glance said.

In most places that wish-cycling has real consequences, but in some cities and states, including New York, people can take those plastic bags to collection bins at some grocery stores so that material gets a second life as something like a deck chair.

In certain places, for those willing to venture outside their home, recycling opportunities don’t end at the curbside.