In some ways, it’s hard to believe it’s been five years since Mo’Ne Davis blazed her way into a household name with a transcendent Williamsport performance. She wasn’t merely the first girl to win a game at the Little League World Series, she tossed a two-hit shutout, with no walks and eight strikeouts in her six innings of work. She struck out the side in the sixth, all swinging, all overpowered on high fastballs. In a tidy but overpowering 70 pitches, she had captivated a baseball-loving nation and changed the very definition of what it meant to throw like a girl.

And yet, as she appeared at the Library of Congress Thursday night as a guest of honor to speak with “Baseball Americana” (which closes Saturday) exhibit curator Susan Reyburn and introduce a screening of “A League of Their Own” on the lawn, that crazy summer seemed like a lifetime ago, even while Davis’s own adult life, the earliest moment most people start to make their mark on the world, is just beginning.

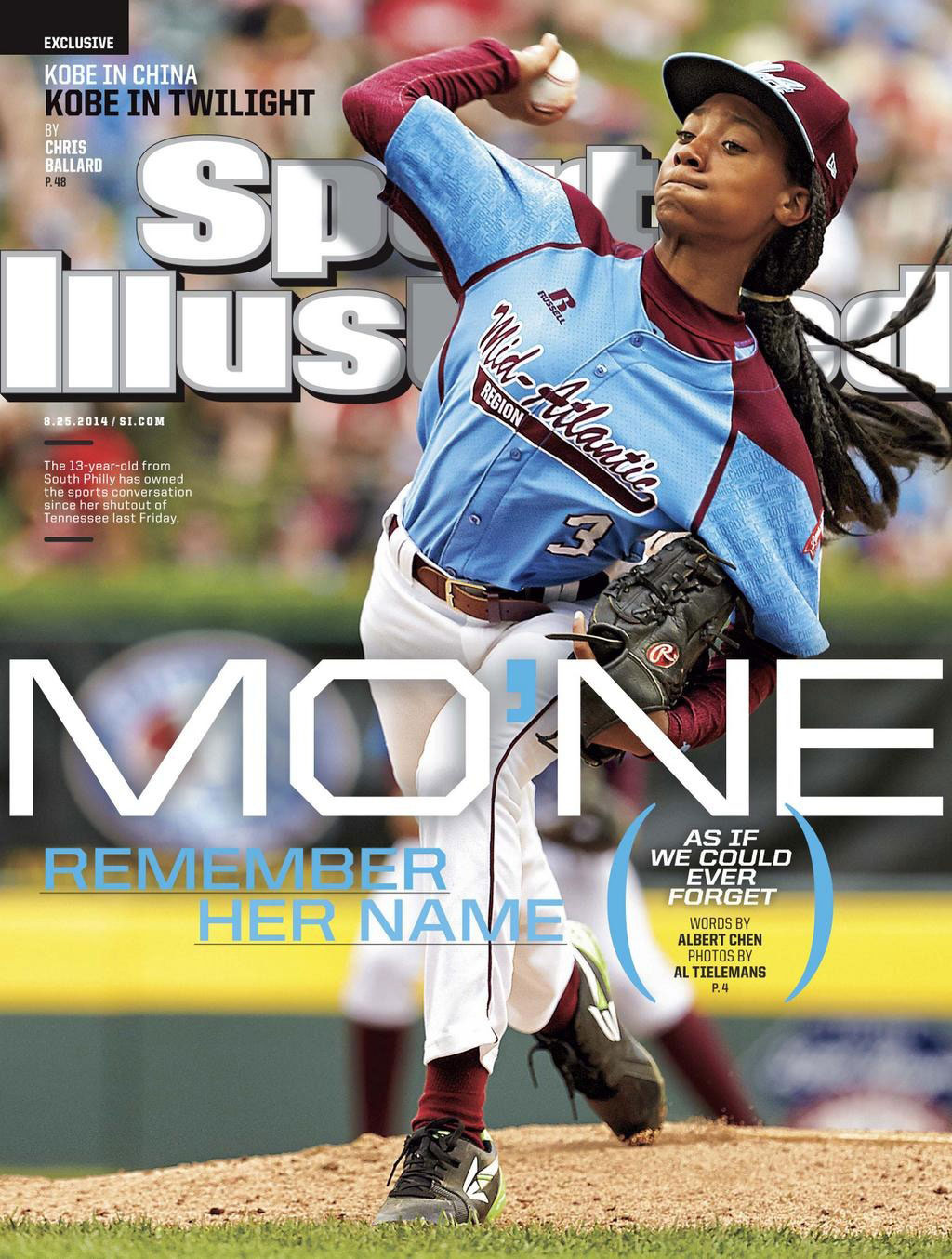

To say that expectations for what Davis’s future might bring following that summer were astronomical is an understatement. In Reyburn’s (and this author’s) favorite baseball movie “Bull Durham,” when young stud hurler Ebby Calvin “Nuke” LaLoosh gets the call to the big leagues, his journeyman catcher Crash Davis reservedly and drunkenly congratulates him without fanfare, offering, “I hope you end up on the cover of Sports Illustrated.” Even more than 30 years after the film’s release, that remains a bench mark in American sports, one that Davis achieved through her star turn five years ago. “Remember her name,” the headline insisted “as if we could ever forget.”

Armed with a 70 mph fastball, the sky seemed to be the limit for her baseball career. But even then, basketball was her favorite sport, as she dreamed of playing point guard at perennial powerhouse UConn. It was fitting, then, that she bumped Kobe Bryant off the cover of the magazine that week.

In Spike Lee’s mini-documentary about Davis, the outsiders he interviews show just how eager America was to project that image of what might be onto Davis’s canvass. One recalls neighborhood boys fighting to claim the role of Mo’Ne as they play, the way they might have previously done with a professional athlete. Another says Davis’ success flips the entire paradigm of throwing like a girl and being a young woman to mean anything: “success, achievement, power, strength, courage.” It’s all a lot to have put on a 13-year-old.

Davis and her mother Lakeisha McLean even met with the Obamas at the National Christmas Tree Lighting, an event from which a picture still sits in the family living room. They gave Davis a note: “You changed the sports world. Keep going. Don’t let anybody stop you.”

While some might read that as further encouragement to blaze new trails, Davis didn’t internalize the message as anything more than a validation that she was on the right track for herself, wherever that eventually would lead.

“For me, it just means to keep being myself, because that’s who I was during Little League,” she told WTOP. “I didn’t change for anybody. I didn’t let anybody change me.”

In 2016, FOX launched “Pitch,” a scripted drama about the first woman to break through into the Major Leagues. The character was a pitcher and a young black woman. It was hard not to connect the dots back to Davis, to remember what she had accomplished two years prior and wonder if she might not make the show a reality just a couple years later.

But nothing is so simple.

Davis was 5-foot-4 then. She’s just an inch taller now, shorter than even notoriously diminutive Houston Astros star Jose Altuve. Her catcher Scott Bandura from the Anderson Monarchs, where she learned to love the game, has grown up to be 6-foot-2. He received a baseball scholarship offer from nearby LaSalle University earlier this summer.

Davis, meanwhile, is off to Hampton University in a month, just like incoming college freshmen all across the country. She pursued basketball for 2 1/2 years, plying her athleticism on the AAU circuit. But a sprained ankle cost her valuable playing time during the height of college recruiting, and she found her way back to the diamond.

“Once I rolled my ankle and I had that time off, I really thought about what I wanted to the next four years,” she said.

She’ll play softball for the Pirates, holding down shortstop, just like she did while not on the mound in her Little League days. And while it’s easy to think of Davis joining an obscure mid-major softball program as something of a letdown compared to the otherworldly expectations many thrust upon her, she’s never seen herself as some posterchild for shattering the hardball glass ceiling, no matter what others have foisted upon her.

“I don’t consider myself an ambassador, but I think it would be pretty cool to just go around and talk to girls who play baseball,” she said. “Nowadays I’m seeing a lot more girls playing baseball.”

Some of those girls came to see her before Thursday night’s event. The D.C. Force girls baseball team, fresh off a tournament win in Toronto, visited the Library of Congress and met with Davis Thursday. Even without Davis shouldering the load of carrying girls baseball into the future, what she accomplished five years ago is still a milestone and she remains a celebrity to those looking to follow in her footsteps, signing jerseys and taking photographs.

Davis’s SI cover is in a display case at the exhibit, along with a Rockford Peaches jersey and other artifacts of women’s impact on baseball. She posed with the Force for a photo in front of it, underneath a quotation from Lisa Fernandez, the former U.S. National Softball Team pitcher.

“If you have a love for this game, then show it. And encourage a girl to do the same.”

As Davis heads to Hampton, Ashton Lansdell will matriculate to Georgia Highlands College, where she will play baseball starting next year. Like Davis, Lansdell was a pitcher first, but will be moving to being a full-time position player. Meanwhile, a number of the Force players have begun to play on their respective high school teams. Perhaps one of them will be the first to break through at the Division I level, to take the next step, picking up the torch.

Davis hit the end of her AAU eligibility this summer, and she’s been playing a lot of baseball in the space it has left open in her schedule. While she’s got no immediate plans to pick up a baseball again, to pitch again, to see where that might take her next (Hampton doesn’t have a baseball team), you’d be wise to still not forget Davis’s name. You never know what she might do next.

“People’s minds change — mine did,” she said. “So it’ll probably change again.”