WASHINGTON — The Major League Baseball All-Star Game swept through D.C. last week. And while there is little trace left around Nationals Park that it was ever here, there are still some exhibits around town for baseball fans to enjoy, including a unique, artistic take on the history of Cuban baseball.

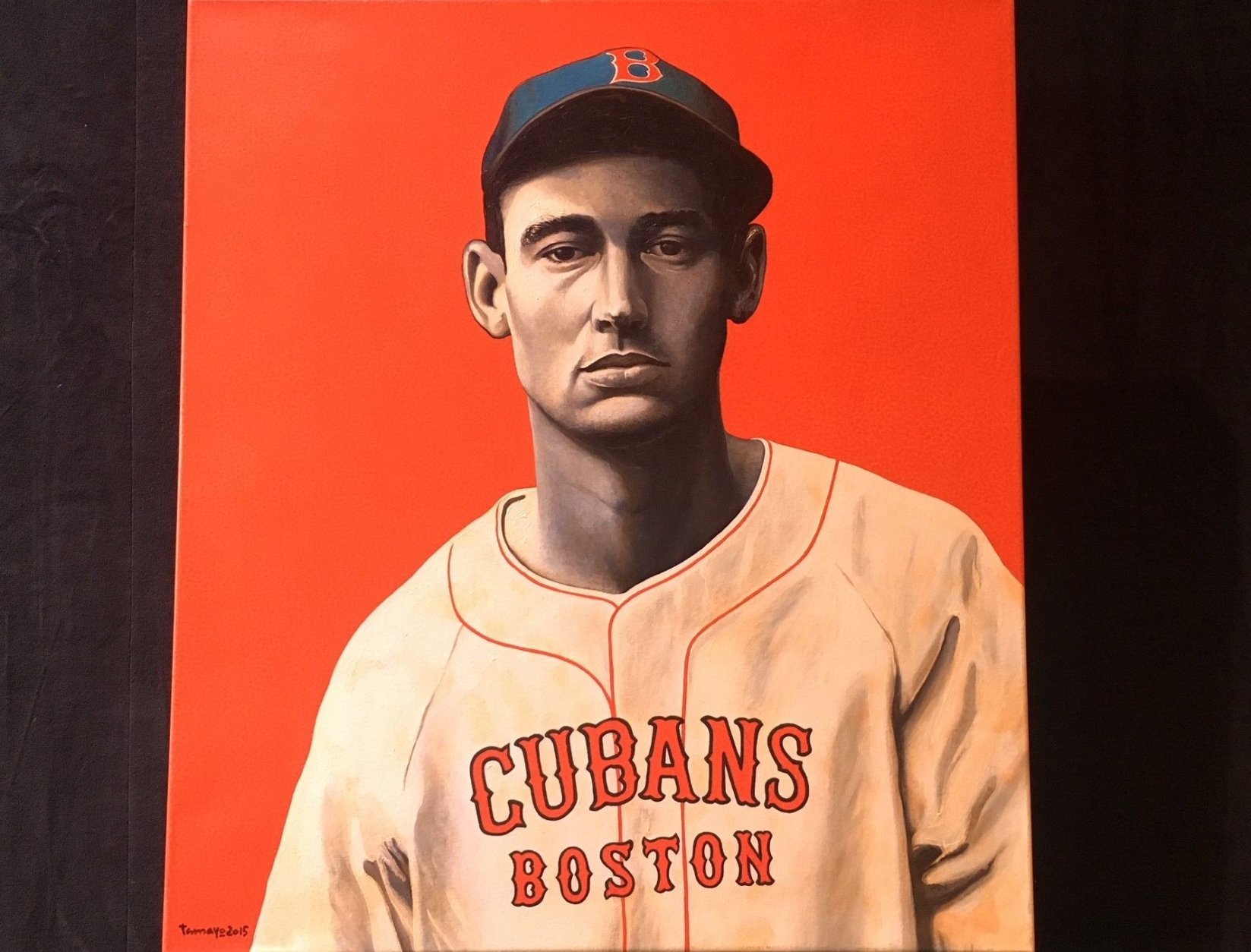

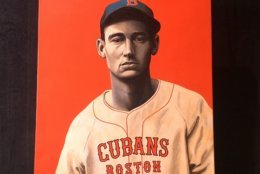

“Cuban Slugger” is an exhibition displaying roughly 35 of Reynario Tamayo’s 54-piece collection, which he has created over the last three years. After debuting at the Galeria Habana in Cuba, it appeared at last year’s All-Star Game in Miami, and will be on display through Sunday in the main lobby area at Arena Stage in Southwest D.C., thanks to the Caribbean Educational & Baseball Foundation and Kendall Art Center.

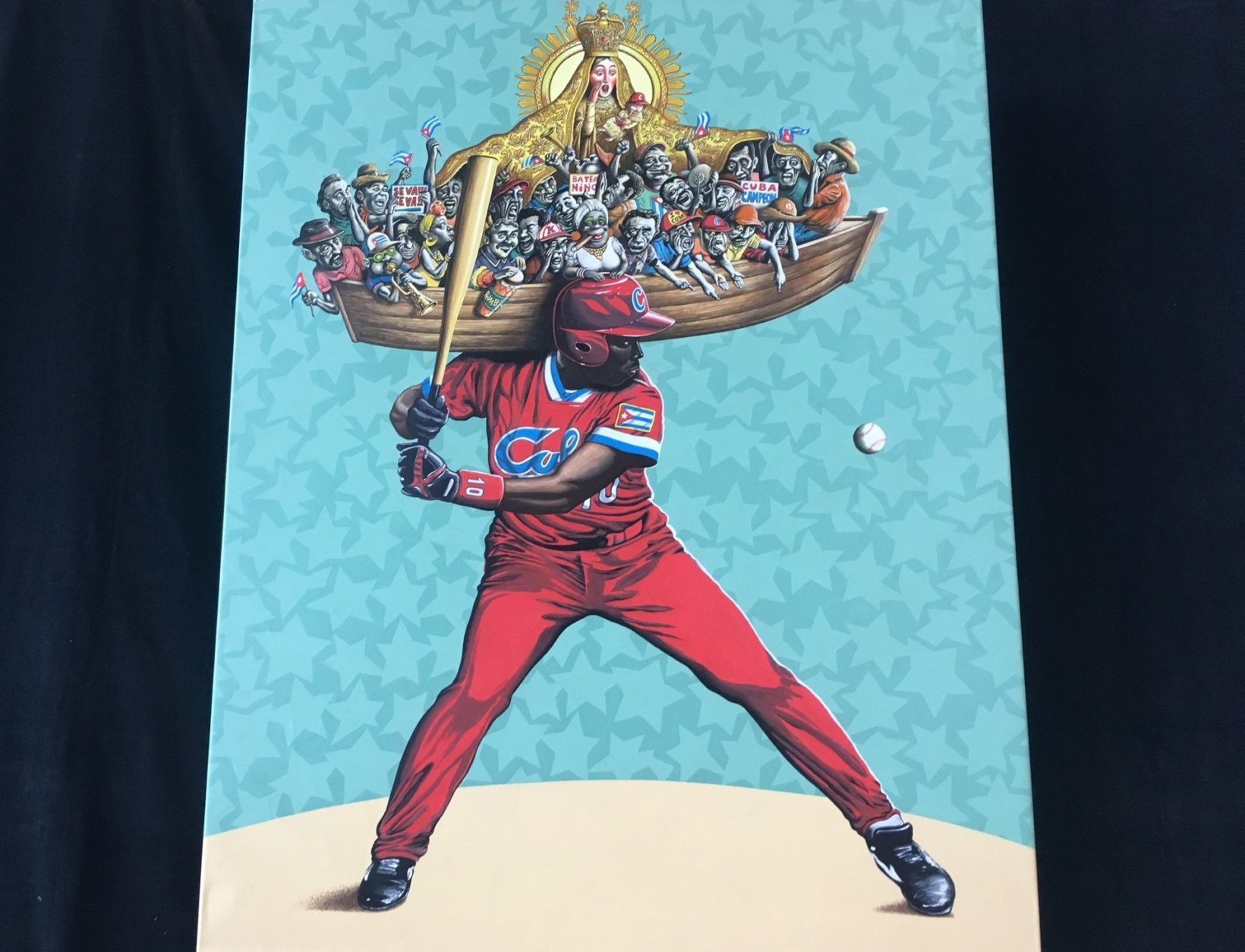

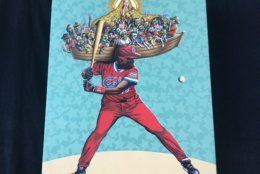

If there’s a piece that symbolizes the country’s complicated relationship with Major League Baseball, it is perhaps one of the first ones you see when walking up the stairs. It depicts legend Omar Linares, who hit .368 with 404 home runs over 20 seasons in the Cuban League, waiting for a pitch, bat above his shoulders, supporting a wooden boat full of his countrymen.

“He’s carrying on his shoulders the weight of the Cuban nation, just as he’s about to hit the ball,” Tamayo told WTOP through a translator. “When Cuban players are up at bat, they feel a tremendous amount of pressure, sometimes more than other players from the Caribbean or other places around the world. This is a reflection of the passion the Cuban people have for baseball.”

The boat represents the vessel of Our Lady of Charity, the patron saint of Cuba. Tamayo says it’s not meant to reflect the arduous journey those who leave the island often must endure to reach the United States in pursuit of their dream. But he’s optimistic about the possibility of change in the way players arrive in America.

“I hope MLB can reach an agreement with the Cuban baseball authorities so that players can come here without risking their lives.”

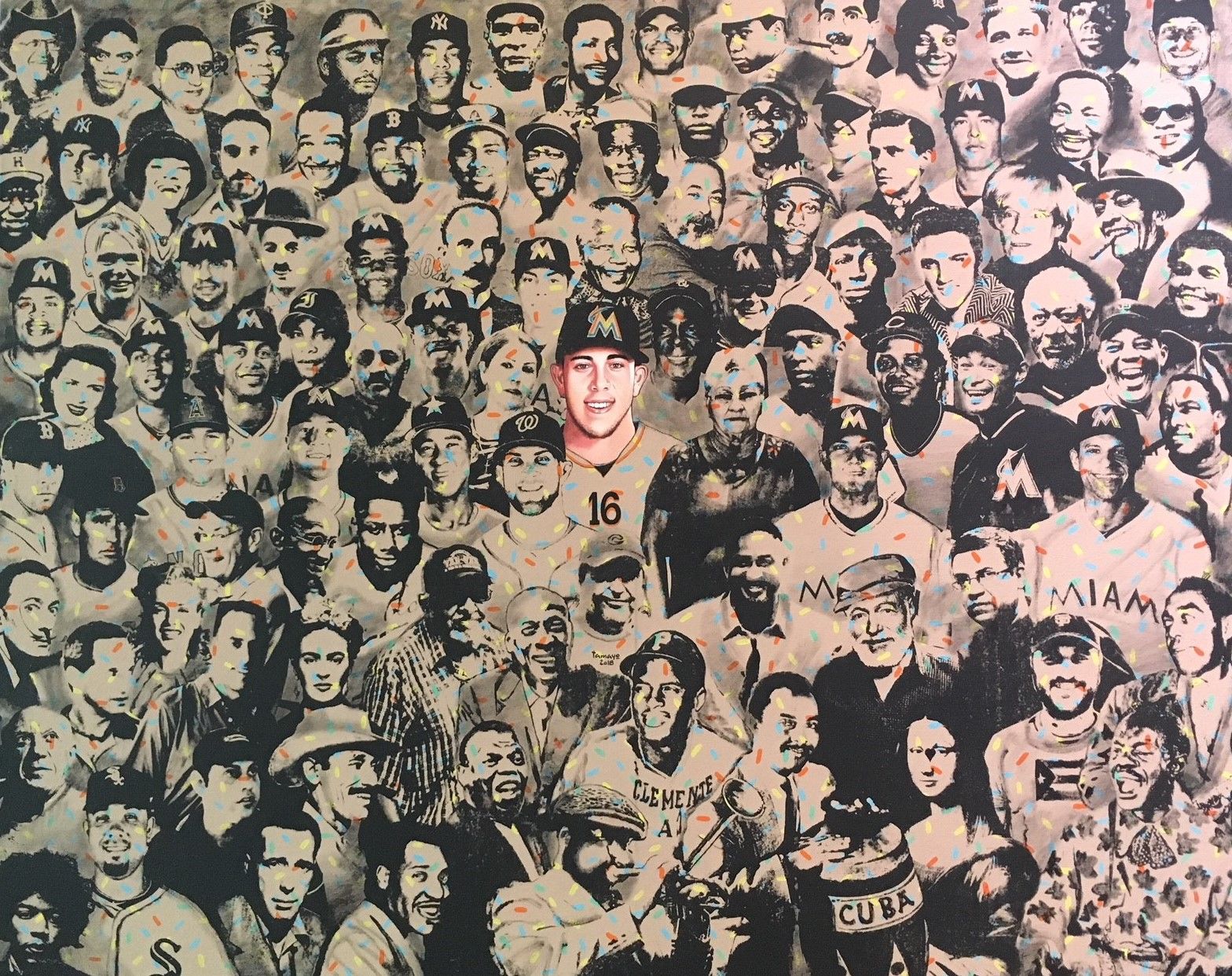

Cubans have been playing baseball in America since as far back at the 1800s. The first Cuban to play in the U.S. was Esteban Bellan, who played six seasons in NABBP (1868-1873) and was also the first Latin American born player to play professionally in America.

Rafael Almeida and Armando Marsans were the first Cubans in MLB, making their debuts the same day — July 4, 1911 — for the Cincinnati Reds. There have been lighter-skinned Cubans in professional American baseball throughout the game’s history. But Afro-Cubans who came to the states were relegated to the Negro Leagues. That makes Jackie Robinson a figure just as influential for Cuban baseball as American baseball.

Robinson actually played in Cuba two weeks before he broke the color barrier in spring training with the Dodgers.

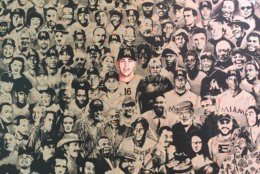

“At the time, there was a constant presence of American players on the island of Cuba, and there were a lot of Cuban players up here in the U.S. as well,” said Tamaya. “Baseball has always united the two countries.”

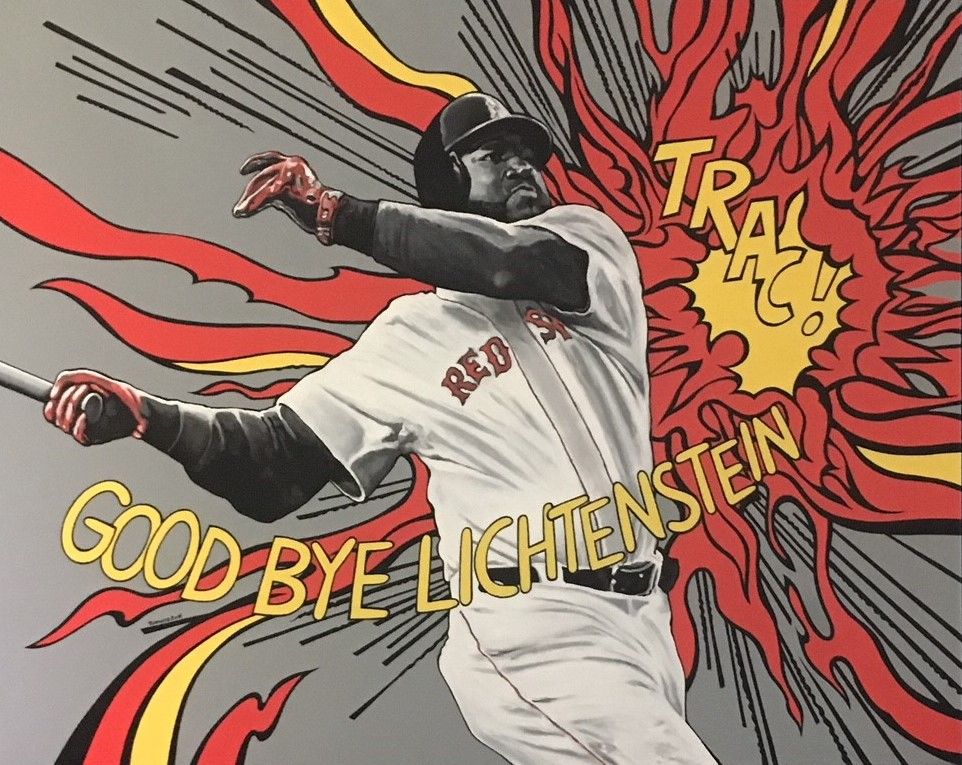

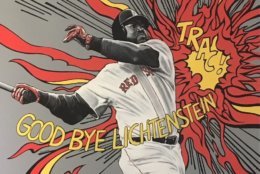

While Robinson factors in prominently to Tamaya’s display, he also pays homage to a number of famous artists by connecting them to famous baseball players. Babe Ruth is intertwined with Vincent Van Gogh. David Ortiz channels Roy Lichtenstein. It all lends a whimsical surrealism to the pieces.

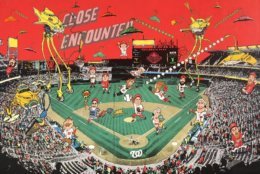

That extends to a depiction of Nationals Park under a “War of the Worlds”-like invasion by Havana taxis. It even features Hugh Kaufman, the Rubber Chicken Man known for “sacrificing” the fake animals in front of Nats Park to ward off bad luck.

“Despite the ‘attack,’ it’s actually a celebration at Nationals Park,” said Tamayo.

One of Tamayo’s pieces, depicting the patron saint of Cuba helping White Sox slugger Jose Abreu swing a bat, has been requested by the Smithsonian to appear in the Museum of National History. The artist is hoping to add to that honor with a more permanent space in another museum.

“The ultimate dream with this exhibition is to get it into Cooperstown,” he said.

“Cuban Slugger” is free and open to the public from noon to 8 p.m. through Sunday, July 29.