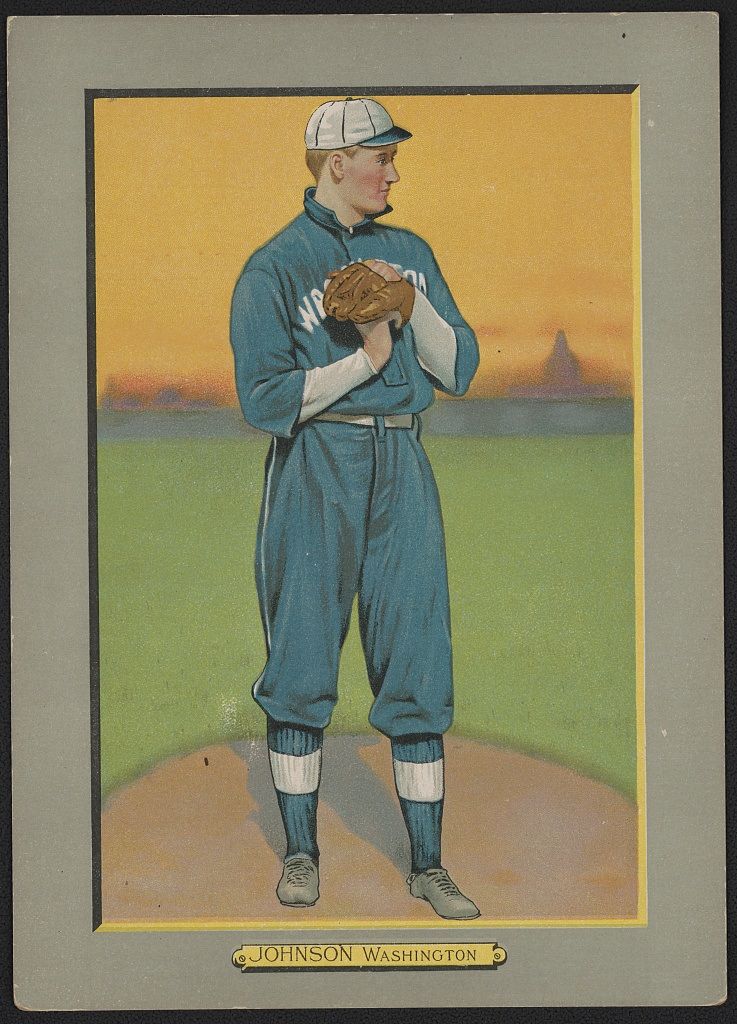

WASHINGTON — Every baseball fan knows the tale of Civil War general Abner Doubleday, who supposedly invented the sport in Cooperstown, New York, in 1839. But for those with an itch for the story of baseball’s actual origins, as well as how the game has evolved into what it is today, the Library of Congress has a salve.

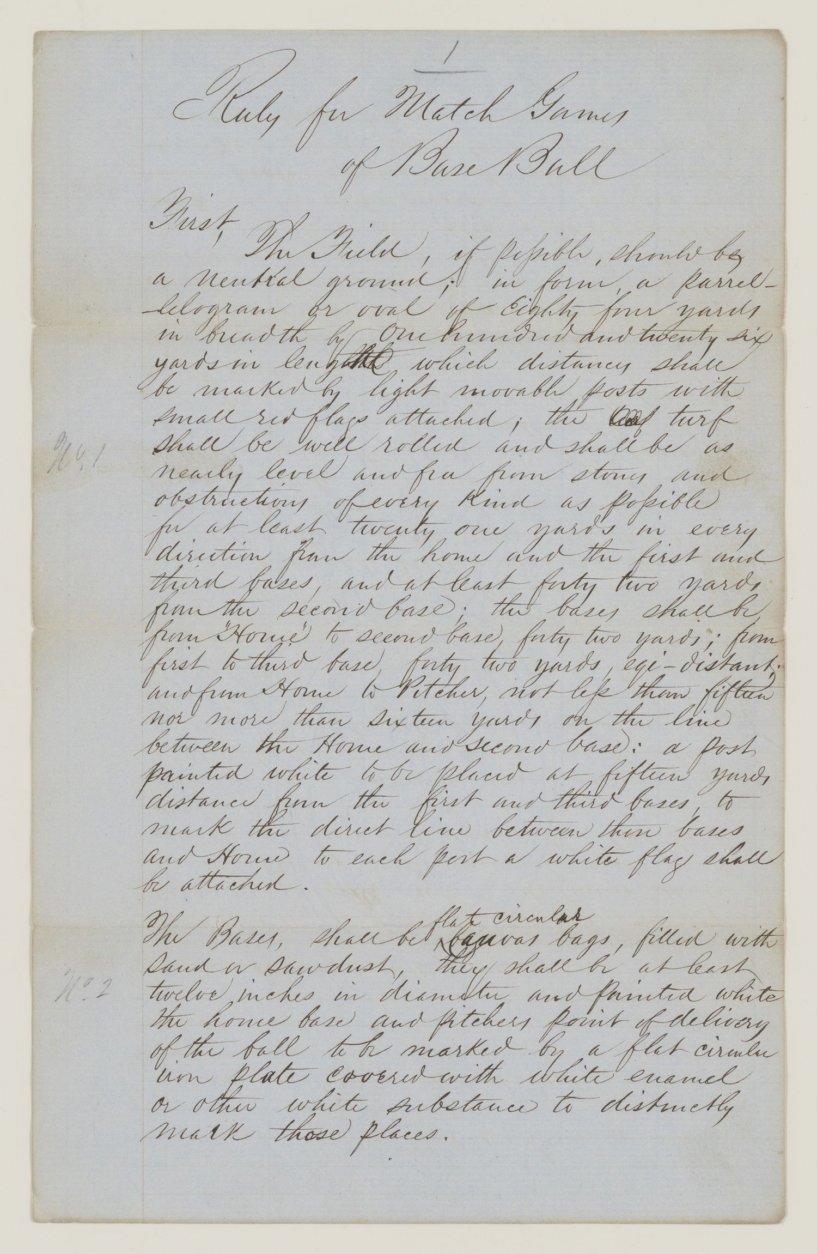

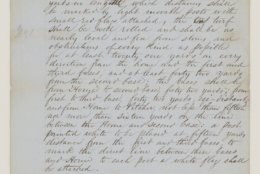

This summer, the museum will open “Baseball Americana,” a collection of artifacts and interactive games rooted in America’s Pastime. Included in the documents are the original, handwritten “Laws of Base Ball” — two words, as it was written then — the first set of uniform rules for the game as laid out at an 1857 convention, complete with handmade corrections.

Once thought to be lost, the game’s “Magna Carta” was sold at a 1999 auction, but its significance was not fully understood until a more recent sale in 2016. At a convention in 1857, many of the rules that have endured through today — nine players to a side, 90-foot base paths, nine-inning games — were hammered out.

“What wasn’t realized was that the working documents had survived,” Susan Reyburn, curator of the exhibit and co-author of the 2009 book “Baseball Americana: Treasures from the Library of Congress. “You can look at these documents, see the proposed rules for baseball, and see where things were crossed out, edited, what was voted on, what was rejected. Some of the major items in baseball today grew out of that conference.”

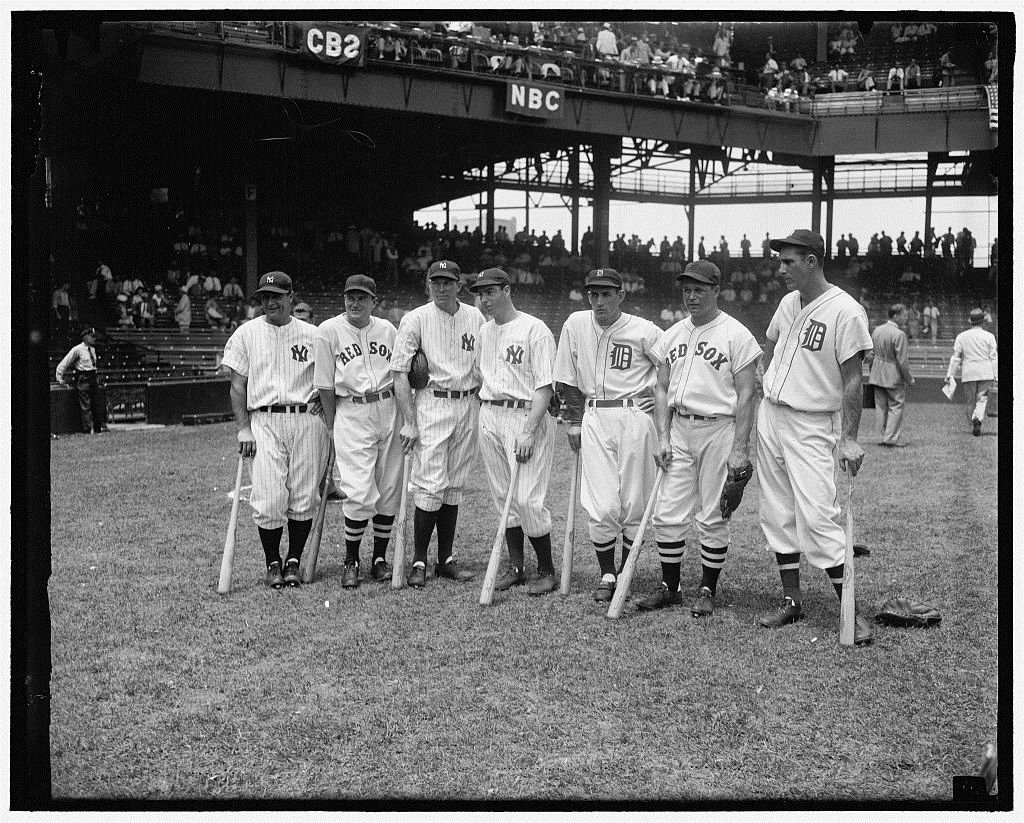

The museum has had a number of items in its collection since that book was written, but this year’s MLB All-Star Game at Nationals Park finally provided the excuse to turn everything into an exhibit. It will open to the public on June 29 and will run for a full calendar year.

“Ever since then it had been in the back of our minds that we had a lot of wonderful material that you wouldn’t see anywhere else, and that we would love to get that on exhibition,” said Reyburn.

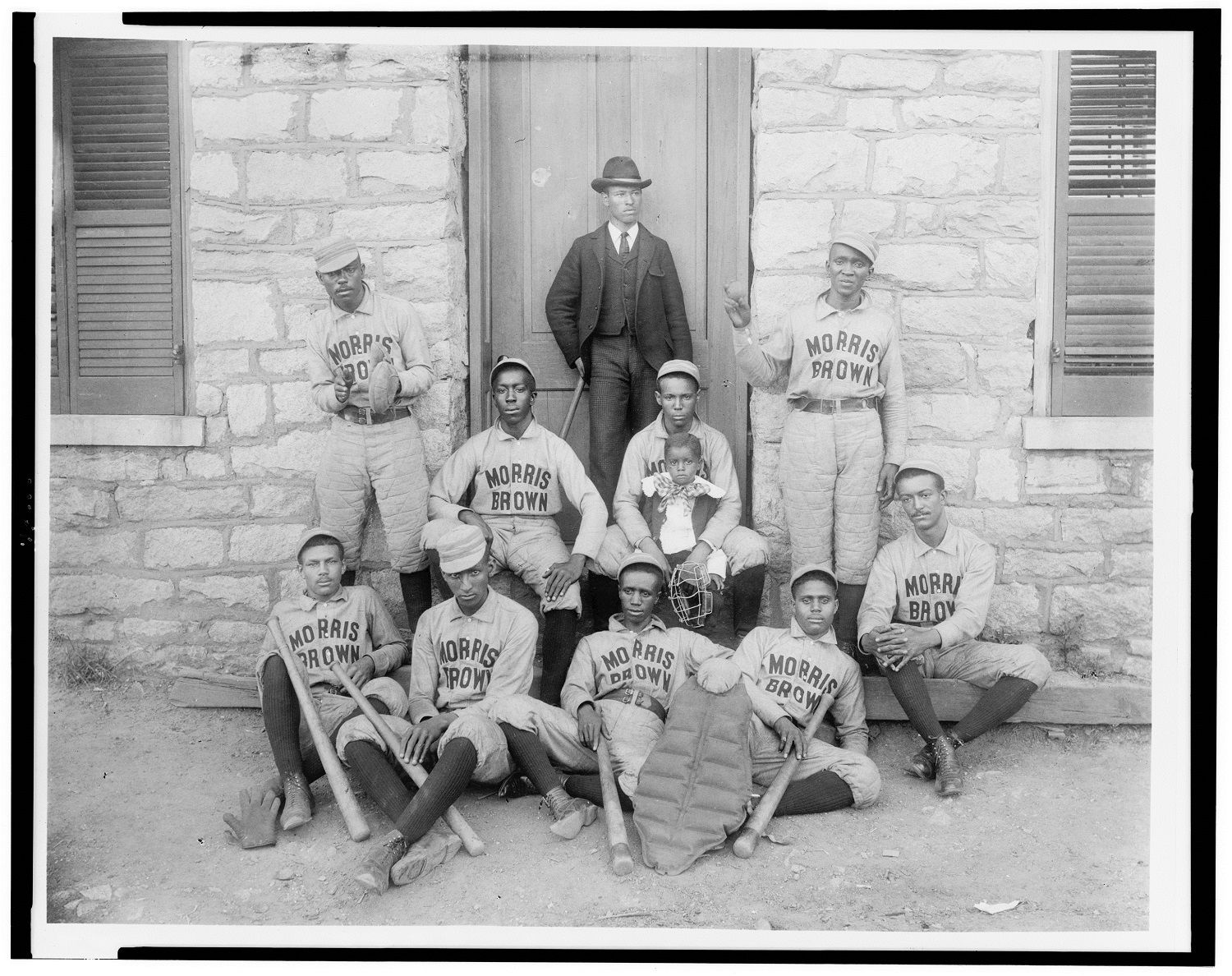

Perhaps even more enlightening than the original rules are the pieces of evidence that the game’s origins date back not just before Doubleday, but before the United States.

“We have a diary from a student who was at the College of New Jersey, which later becomes Princeton University, and he writes in 1786 about playing baseball, and that he’s not a very good hitter,” said Reyburn.

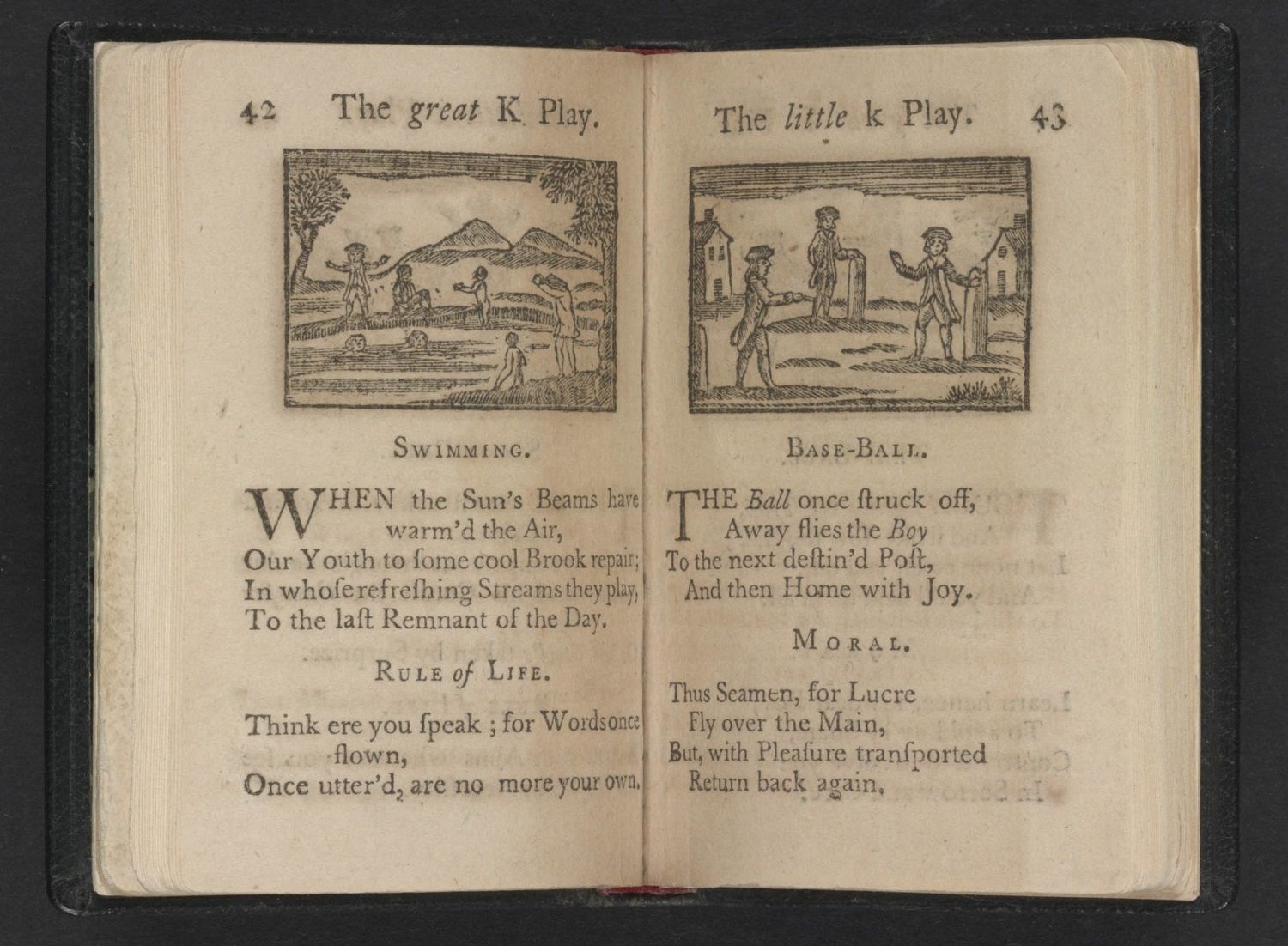

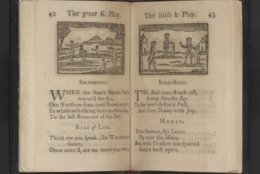

They also have a copy of the first known printed reference to the sport’s name. That came in a children’s book in 1787, which was actually a reprint of a book that appeared in England in 1744. In the visualization of the game, there were three posts instead of bases that the players ran around.

“It kind of just captures your imagination that this is a game that is going on in the Colonial period, early American history, and we’re still playing it,” said Reyburn.

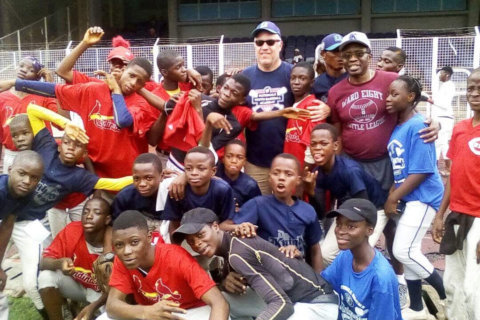

But the history of game, or at least elements of it, stretch much further back than that. And again, contrary to popular belief, they stretch beyond American shores.

“I think people are going to be surprised when they see an image that we have from ‘The Romance of Alexander,’ which was a medieval text,” said Reyburn. “In the border illustrations there you see monks and nuns from the 14th century with a bat and ball, and several of them kind of standing out there ready to catch.”

While the museum tried to be as equal as possible to all teams in terms of historical contributions, there will be plenty for Washington baseball fans. That includes a lineup card from Bryce Harper’s first Major League game, against the Dodgers in Los Angeles back on April 28, 2012.

The exhibit will open with some yet-to-be-announced celebrity appearances at launch. There will also be a number of interactive activities, including the chance to pose for your own baseball card with modern and historical backdrops, fun facts and trivia from ESPN Stats & Info, and a kids section including hands on samples of old catcher’s masks and AstroTurf.

“You are going to see things that you probably have never seen before, even if you are a lifelong fan. And if you’re not a fan, I think you’ll see a lot of fun material, a lot of interesting videos, a lot of things that will capture your imagination,” said Reyburn.