VERO BEACH, Fla. — The first thing you notice is the lamps.

Sure, the brilliant blue skies dotted with cotton ball clouds draw the eyes upward as sunlight bathes the emerald fields below, but as anyone who has spent any time at Spring Training will tell you, that’s just what Florida looks like this time of year.

No, it’s the lamps, the white spheres with the red laces that line the quiet streets of the legendary Dodgertown complex just inland from Vero Beach that set the place apart. Like the entire complex, they are of another time, a reminder of a simpler, more communal, more fan-friendly sport, of a past getting more difficult to remember as the game inches inexorably into the future.

The Los Angeles Dodgers left this place in 2009 for newer — if not greener — pastures in Arizona.

It was a move that made sense in many ways: putting their spring complex closer to their big league home; upgrading to the newest, state-of-the-art facilities; splitting a stadium with another club; reducing the travel involved in reaching other teams’ sites as more and more clubs moved away from Florida’s east coast.

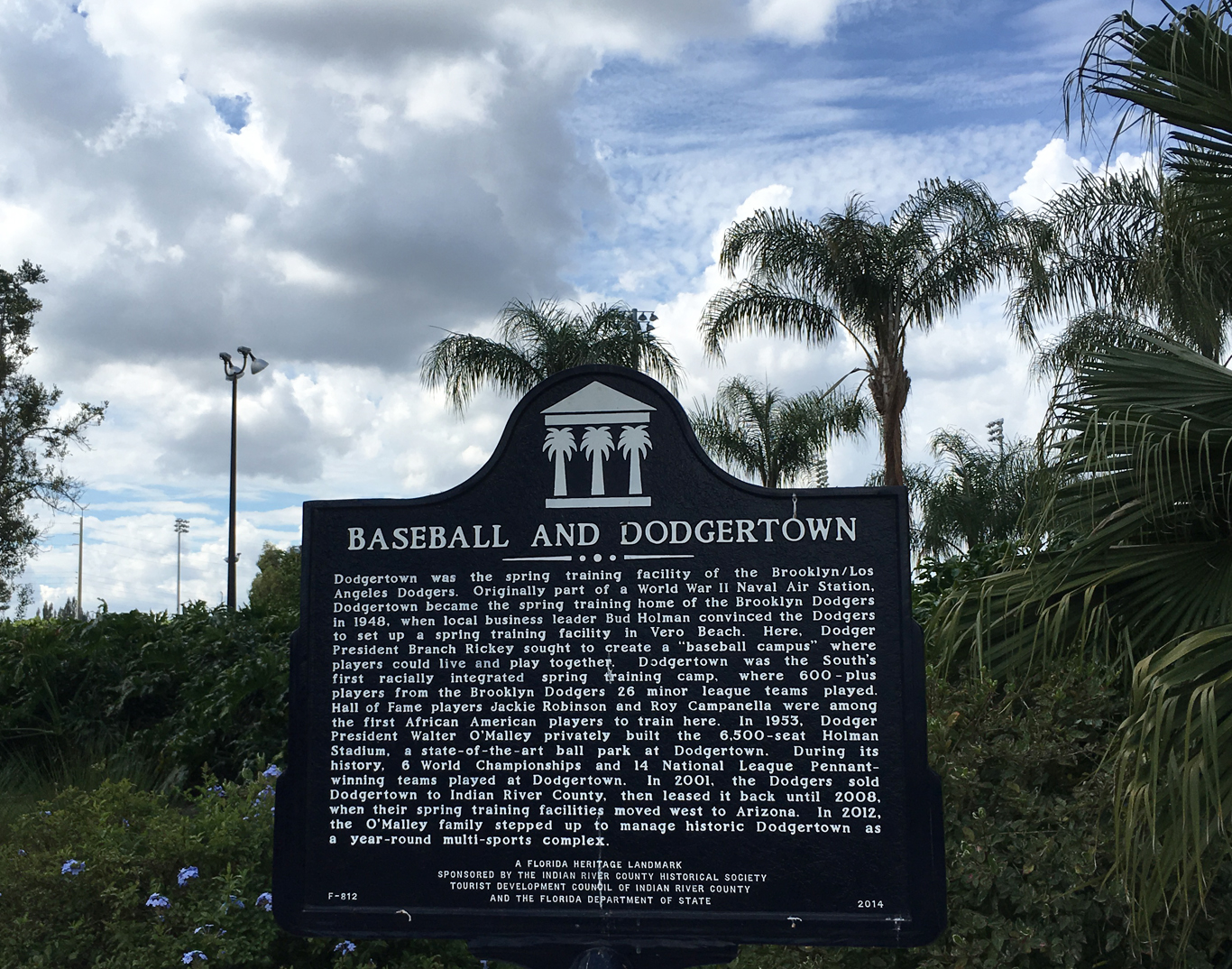

But the Dodgers left more than just a simple complex behind in Vero Beach. Dodgertown’s history runs deeper than any other such site, its traditions evoking laughter and introspection from those who lived them.

(WTOP/Noah Frank)

Pat O’Conner was a fresh-faced Ohio University student who knew nothing more of Vero Beach than what fit on a flyer handed out on campus when he took an internship at Dodgertown in December of 1980. His experience would be transformative one, impacting him the rest of his career up through his current position as President and CEO of Minor League Baseball.

“Once you got there, it took little or no time to just be absorbed,” he told WTOP. “That place just kind of envelops you, when you start making the connection of who’s coming in three months and who’s been there for 35 years.”

From Jackie Robinson to Sandy Koufax to Mike Piazza, generations of Hall of Famers have called Dodgertown home in February and March. But the Dodgers are hardly the only franchise with a laundry list of legends. The difference at Dodgertown was their accessibility to the fans.

“Wherever you looked, there was somebody famous walking down a street or on a field,” said ESPN baseball analyst Tim Kurkjian, who covered visiting teams at Dodgertown for better than 15 years. “Once you went to Dodgertown, you couldn’t help but see Dodger blue and feel Dodger blue every step that you took.”

That included on the field at Holman Stadium, where the dugouts are literally just that — holes in the dirt, largely unprotected from the sun, the crowds, or errant foul balls.

“Those dugouts there were like nothing I’ve ever seen,” said Kurkjian. “That was kind of what made Dodgertown so great — it just didn’t look like anything else … It almost brought the players even closer to the fans sitting around them.”

The Dodgers took over an old Navy housing base to build their complex, converting the barracks into villas where the players lived during the spring. That created a collegial atmosphere unlike anything seen at Spring Training sites today, with a communal dining hall and recreation areas for families.

“That was the beauty of this place,” said Historic Dodgertown director of marketing and communications Ruth Ruiz on a tour of the facility. “It was never shielded.”

That atmosphere extended to the hospitality for writers like Kurkjian, who were often blown away by the accommodations, especially in comparison to what they were accustomed to.

“At the places where the teams I covered trained, you would get maybe like a sandwich in this little shack before the game,” he said. “Then we went to Dodgertown and they literally had shrimp cocktail for the writers before the game.”

If that wasn’t fancy enough, there was an actual bar, open to all, including the working media.

“Any media, visiting or home, could go in there and have a drink, have a beer, while they’re writing their story,” said Kurkjian.

Players would wander in after games. Kurkjian even said he saw Davey Johnson, who managed the Dodgers at the time long before he took the same job in Washington, drop by for a beverage.

“It was just amazing to me that this was how things were done in Dodgertown,” said Kurkjian.

Christmas in March was another thing done at Dodgertown that everyone seems to remember.

Right in the middle of March, before the team broke camp for six months of hellish travel, there would be a full-blown holiday celebration.

“Families are away from each other quite a bit during the season, so the O’Malleys wanted to give them time to be with one another,” said Ruiz.

It’s the kind of anecdote that explains the permeating philosophy of the place. But the attitude extended beyond family in a time before the Civil Rights Movement, when baseball was a step ahead of the rest of American society.

“It’s a cultural icon,” said O’Conner. “It’s a place where not only was baseball changed, but America and the world underwent change because of what was done there.”

Vero Beach itself stands in stark contrast to the spring break-infested shores of Miami, a sleepy beach town where families and retirees lunch leisurely at sidewalk cafes and adolescents vie for attention by pulling wheelies in the bike lane.

But in the 1950s, it was a place where African-Americans weren’t welcome, even those who wore Dodger blue. That included Vero Beach’s golf courses.

So the O’Malley family, which owned the club at the time, built two golf courses on the property to allow all their players a place to play. While some believe the courses were built specifically for Jackie Robinson or Maury Wills, former Dodgers owner Peter O’Malley confirmed that they were built for the express purpose that all Dodger players could play together, the same way they did everything else as a unit at Dodgertown.

“The team traveled together, stayed together, ate together, roomed together, golfed together,” said Ruiz.

Ruiz, like seemingly everyone else connected to Dodgertown, has history with the Dodgers, having worked as a team publicist from 1986-2001. As part of a staff of about 10, she helps manage the site, which includes constant reminders of the rich history forged there. Classic photos line every wall of the conference center, anchored by the Jackie Robinson Room.

“As a caretaker and a steward of the game, we are losing so much history and respect for the history of the game,” O’Conner said. “If we lose the Jackie Robinson story at its roots and the battleground where it actually took place, it’s gone forever. If we don’t keep Dodgertown standing, it’ll be paved over and be condos or a strip mall in no time.”

O’Conner knows firsthand all about the struggle to keep the site alive. After the Dodgers left in 2008, there was an effort to find another tenant.

“I was called and asked if I knew of any Major League clubs that might be interested in going back to Dodgertown as a Spring Training site,” said O’Conner.

There wasn’t. At the time, teams were deserting Florida’s east coast for the other side of the state or Arizona. Instead, Major League Baseball had a deal in place to purchase the facility to use as part of their urban youth academy programs. But the financial crisis hit and MLB left the deal on the table.

“They didn’t want to take an initiative and make an effort as aggressive as that when they had just froze salaries and laid people off, so it kind of fell apart,” said O’Conner.

To his delight, the Minor League Baseball board of trustees stepped in to pick up where MLB had left off.

Minor League Baseball ran the site for a couple years as the Vero Beach Sports Village, denied the ability to use the Dodgertown moniker, lest they fork over $1 million royalty fee to the McCourt family that owned the Dodgers at the time.

It wasn’t until Peter O’Malley — who, along with his father Walter, owned the Dodgers for nearly 50 years from 1950-98 — stepped in along with his sister Terry Sidler and former Dodger pitchers Hideo Nomo and Chan Ho Park to take ownership of the property in 2012 that the name was restored to Historic Dodgertown.

They made upgrades to help it compete in a 21st-century sports landscape. A cloverleaf field for youth baseball and softball was added. So was a 100 yard-by-130 yard grass field, which can be used for football, soccer, lacrosse or any number of other sports.

The practical has already somewhat replaced the sentimental.

Walter O’Malley built a heart-shaped pond built on the nine-hole course for his wife Kay. That’s where the recently-constructed cloverleaf field now stands. The rest of the course is overgrown, unused. It is owned by the city and was recently put up for sale, but the City Council rejected a bid to put 280 homes on the site.

The future of the golf course remains up in the air, as does the long-term potential for the site.

A half dozen NFL teams have held camps there over the years and several Canadian Football League teams continue to use Dodgertown today. The Washington Freedom, a precursor to the Washington Spirit, trained there. Just a few weeks ago, SK Wyverns of the Korean Baseball Organization finished their own spring training on site.

“The goal for Historic Dodgertown is to have it and keep it a multiuse facility,” she said.

The answer to what happened to Dodgertown is an incomplete response, one still being written by baseball’s present. Other sports continue to find the facility, including rugby last year. But could a Major League team still rediscover the magic the Dodgers once captured in Vero Beach?

“I’m happy to hear that Somebody’s playing baseball there,” said Kurkjian. “If the Dodgers aren’t going to train there — and again, I don’t blame them for moving to Arizona — somebody should be playing baseball on such a historic site.”

O’Conner’s not ready to give up yet. He knows he’s biased and happily admits it. But he also knows as well as anyone what Dodgertown offers. With an airport just across the road and now five teams training within 70 miles of Vero Beach, it no longer seems like such an impractical place to perhaps host a Major League team for Spring Training once again.

“If I owned a club, if I was a general manager of a club — if I had the say — I would look very hard at going to Dodgertown and training my team,” said O’Conner. “If you want to immerse your club in baseball, and you want to create a team, and you want to build a champion, I can think of no better place to do it.”