This article was republished with permission from WTOP’s news partners at Maryland Matters. Sign up for Maryland Matters’ free email subscription today.

A state audit shows at least eight Maryland school systems didn’t use $12.3 million designated for students in underserved communities.

According to the document from the Office of the Inspector General for Education, officials with the Maryland State Department of Education (MSDE) didn’t provide training and guidance for local school officials to utilize what are known as concentration of poverty grants.

Those grants are to aid students inside buildings designated as community schools, which receive services such as before- or after-school tutoring, access to mental health professionals and educational field trips. Community schools, which are gradually being established around the state, are part of the Blueprint of Maryland’s Future education reform plan.

Two pieces of legislation focused on community schools are part of this year’s Legislative Black Caucus of Maryland set of priorities. The bills are proposed to help expand the number of community schools in school systems with fewer than 40.

“Several [school districts] shared frustrations about the lack of clarification or guidance by MSDE staff about whether certain items, positions, or services could/could not be procured using [concentration of poverty] funding,” Inspector General Richard P. Henry wrote in last week’s audit. “Specifically, [the districts] advised that MSDE staff would primarily provide only verbal guidance regarding how to spend CoP funds on wraparound services, and little to no written approval or guidance was provided.”

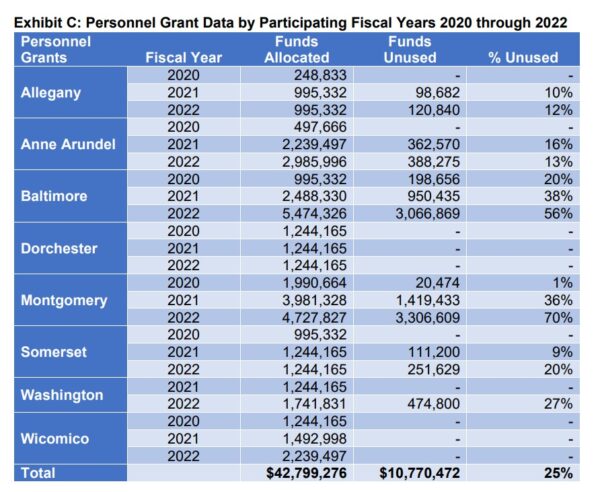

The audit, which reviewed records from July 1, 2019, through Jan. 31, 2023, noted about $1 million was returned to the state. The “selected” school systems, also referred to as local education agencies, or LEAs, that were investigated were Allegany, Anne Arundel, Baltimore, Dorchester, Montgomery, Somerset, Washington and Wicomico counties.

According to the audit, money from the concentration of poverty grants is disbursed in two portions:

- Personnel grants: A fixed amount to hire a community school coordinator and a health care practitioner.

- Per-pupil grants: Money used to provide various wraparound services that can include additional school counselors, English language leaner classes and professional development for teachers and other staff.

However, the audit shows personnel grants allocated between fiscal years 2020 to 2022 were only used in Dorchester and Wicomico counties.

Some local school officials used the concentration of poverty grant funding to pay consultants to train staff on how to use the money. One example in the audit noted a school system entered into a five-year, $4.1 million contract to receive “continued technical support in implementing a community school strategy.”

Senior staff with the MSDE weren’t aware of this going on, the audit said, but “LEAs appropriately reported these training costs to MSDE, but MSDE did not have any follow-up questions regarding these expenses. This absence of follow-up appears to be attributable to MSDE’s lack of adequate controls regarding LEAs’ submitted reports and expenditures.”

A recommendation from the audit to the department: develop a strategy for communicating policies and procedures to all school staff. In addition, the department should establish a team of subject matter experts, legal counsel and other stakeholders in the process such as representatives from the Blueprint Accountability and Implementation Board. The board, known as the AIB, oversees the education reform plan through 2032.

Responses

Interim Superintendent of Schools Carey Wright, who began working as the state’s public schools leader in October, wrote in a letter dated Feb. 1 that the agency “is committed to continuously improving its processes and internal controls…”

The department submitted several responses to the inspector general, including that a concentration of poverty grant program manager continues to coordinate the development of policies and procedures that began in November. A draft of the procedures will be shared with the AIB, with full implementation estimated for March 1.

The program manager is coordinating an annual review process of the concentration of poverty grant policies and procedures with stakeholders to be implemented by July 1, the agency said in response to the audit.

One recommendation where the department disagrees with the inspector general was a suggestion to temporarily pause specific finance and program activities. State law mandates funding for buildings designated as community schools.

The department hired an independent firm in September 2023 to verify grant expenditures incurred from fiscal year 2020 to fiscal year 2023. The contract is set to expire this September.

Henry, the inspector general, wrote in response that the department should “continue to engage the independent firm” beyond September.

The [inspector general’s office] “believes that the State Audit referenced in MSDEs response will not ensure that LEAs are using grant funds in accordance with State law,” Henry wrote.

Shamoyia Gardiner, executive director of Strong Schools Maryland, said it’s not the first time an audit has reported problems with the department.

“It’s not a surprise,” she said after a rainy rally Monday in Annapolis by advocates requesting that lawmakers “fully fund” the Blueprint plan.

Gardiner said the Blueprint board has the authority to approve all implementation plans and assess the spending of funds.

“The fact that didn’t happen is a sign that perhaps we need stronger accountability,” she said.