Hospitals in Maryland have seen a spike in serious injuries and deaths among patients caused by medical errors during fiscal year 2022, according to a new report from the Maryland Department of Health’s Office of Health Care Quality.

The state reported a total of 832 adverse events — defined as an unexpected occurrence related to an individual’s medical treatment and not related to the natural course of the patient’s illness or underlying disease condition.

That included 769 that were categorized as “Level 1” — the most severe classification, meaning the treatment misstep led to a patient’s death or serious disability.

For example, one patient, who had undergone a tissue transplant on one leg, wound up having their other leg amputated due to compartment syndrome, according to the report. In another case, a premature baby was given four times the maximum daily dose of a steroid.

And in yet another case, a patient who needed platelets during surgery wound up dying from bleeding complications because there were no platelets in the hospital, and staff started their operation without checking first.

Maryland Department of Health ‘disheartened’

Maryland’s Department of Health said in a statement the agency is “disheartened by the large jump in adverse events” but also “grateful that hospitals identified these issues, investigated the root cause, and implemented changes to improve care and prevent future errors.”

Chase Cook, the communications director for the department, attributed the growing amount of medical errors statewide in part to the COVID-19 pandemic, said in the statement to WTOP.

“As you know, COVID-19 stretched every health care system in the world to its limits,” Cook wrote.

Medical errors have more than doubled since fiscal year 2020

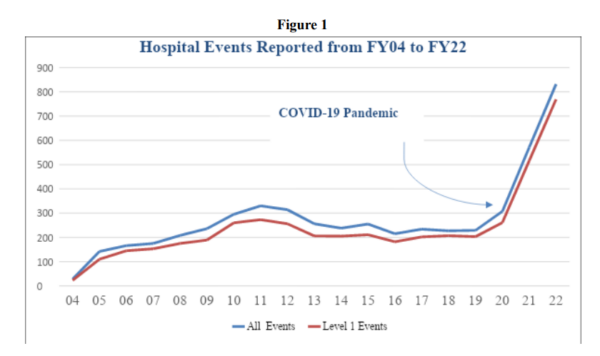

The fiscal 2022 data marks a rise in adverse events compared to the prior year, when state hospitals reported 570 total events, with 517 being classified as Level 1. In fiscal 2020, 310 total events were reported, 264 of which were described as Level 1.

Altogether, the data shows total adverse events at Maryland hospitals increased by about 168% from 2020 to 2022 — more than double.

In fact, this is the largest number of Level 1 events the state’s hospital system has seen since it started recording this data in 2004, according to the report.

This trend was first reported by The Washington Post.

In previous years, the health department has included data on, specifically, how many patients died due to preventable medical errors, but the most recent report did not show this information. Cook said the department struggled to report this data as a result of a 2021 cyberattack that impacted its operations.

“Of the many impacts of this security incident, one of them is the difficulty it created for [the Office of Health Care Quality] in data continuity over time for reports like these,” his statement read, adding that the department is “working to construct the information from records and it will be provided as soon as possible.”

The Maryland Hospital Association, which represents hospitals in the state, said the increase in adverse events came amid the COVID-19 pandemic, which it called a “remarkably difficult time,” and that hospitals across the country also reported increases in medical missteps.

“In our state, new reporting requirements during the past three years can account for some of the largest increases,” Meghan McClelland, the association’s chief operating office, said in a statement. “Maryland is one of only 27 states nationally with extensive reporting requirements for adverse events. This ensures transparency, encourages reporting, and allows for focused training and education to prevent future concerns. Maryland’s hospitals embrace this culture of safety.”

‘Absolutely no oversight of hospitals’

Anna Palmisano, who serves as the director of the advocacy group Marylanders for Patient Rights, told WTOP she thinks the way the data is collected — through hospitals self-reporting their incidents — is “ridiculous.”

“Patients are suffering, they’re dying — there’s absolutely no oversight from the Office of Health Care Quality,” Palmisano said. “They failed to provide the oversight of hospitals and they definitely bear some of the blame for the failure of hospitals to protect vulnerable patients.”

Cook added that after a Level 1 event occurs, the hospital must go through a medical review committee process called a “root cause analysis” and share its findings with the OHCQ within 60 days.

“When it is suspected that a hospital lacks a well-integrated patient safety program, or a complaint is verified regarding an event that should have been reported to OHCQ but was not, an on-site survey of the hospital’s compliance with COMAR 10.07.06 may be performed,” Cook said.

According to Cook, “these enforcement actions do not focus on the adverse event itself” — rather, they focus on whether the hospital is compliant with the requirements of the hospital patient safety system.

“The regulations provide the option of assessing monetary penalties for noncompliant patient safety programs,” he added.

What can be done to address the problem?

Palmisano said she suspects understaffing issues at state hospitals are a key contributor to the sharp rise in medical missteps over the past few years.

“According to Becker’s Hospital Review, we (Maryland) were very lowly-ranked in terms of competitive salaries for nurses,” Palmisano said. “And we also need to support training and education in our state with a promise from the people that we help to support with fellowships, that they’ll at least spend a year in our state working.”

Palmisano cited another Becker’s Hospital Review study, which found that Maryland had the longest emergency room wait time of all 50 states.

She said this issue with wait times “in a sense, parallels some of the terrible problems that we’re having with adverse events.”

Overall, Palmisano said “disheartening” is not a strong enough word for her to describe the magnitude of the report’s findings.

“That’s horrifying and appalling,” she said.

WTOP’s Mike Murillo contributed to this report.