This article was republished with permission from WTOP’s news partners at Maryland Matters. Sign up for Maryland Matters’ free email subscription today.

This content was republished with permission from WTOP’s news partners at Maryland Matters. Sign up for Maryland Matters’ free email subscription today.

There remains a lack of oversight at the Maryland Department of Public Services and Correctional Services when it comes for caring for the well-being of those incarcerated.

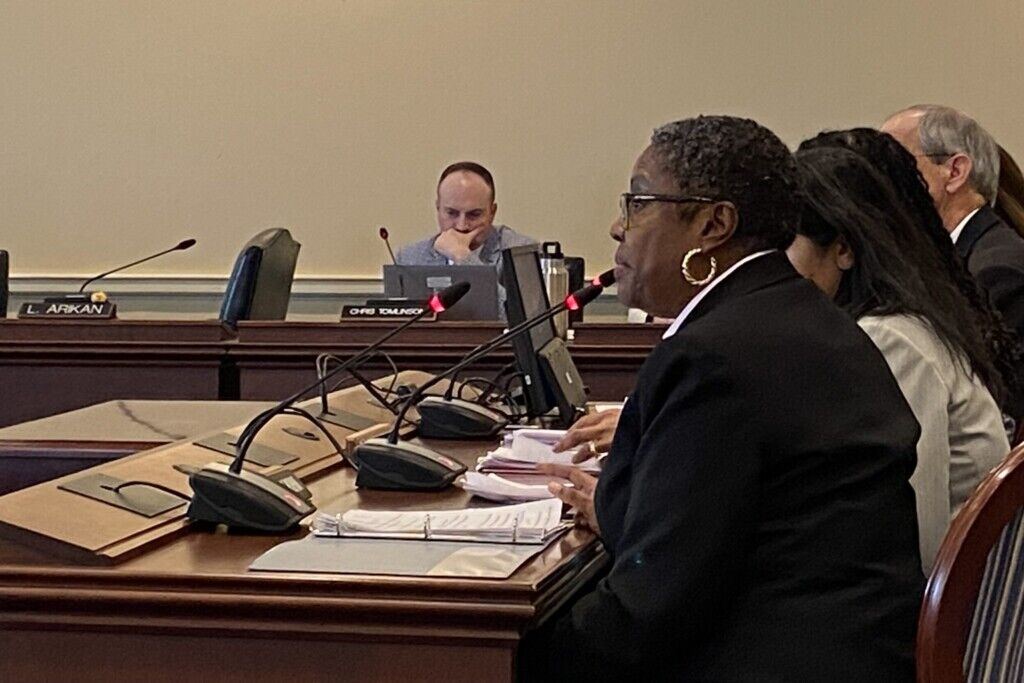

That’s the sentiment of Del. Debra Davis (D-Charles) and other supporters of legislation she’s sponsoring to create a correctional ombudsman in the Office of the Attorney General to oversee the department that manages a dozen state prisons and a correctional annex on the Eastern Shore.

“Our citizens lack transparency and accountability of what occurs behind the walls in our state correctional facilities,” Davis said Tuesday before the House Judiciary Committee. “As policymakers, it is incumbent upon us to have access to this information. We can’t legislate what we cannot see.”

The bill is also assigned to the House Health and Government Operations Committee. Del. Lesley Lopez (D-Montgomery), a member of that panel, asked one of the more than a dozen supporters who testified why an ombudsman position is necessary.

“Everyone needs oversight. We don’t evaluate ourselves,” said Vanita M. Taylor, a division director with the Maryland Office of the Public Defender.

One of the most recent high-profile cases of inhumane treatment in a correctional facility deals with Jazmin Valentine, who was being held at the Washington County jail in July 2021 when she went into labor. According a lawsuit filed last year, Valentine received no medical assistance while she labored for more than six hours before giving birth to her first child alone in a cell.

“This bill does not directly address local jails throughout the state, [but] it will certainly be a catalyst for establishing a reasonable standard of care throughout the [prison and jail] system,” Davis said Tuesday.

According to the legislation, the attorney general would appoint an ombudsman, with advice and consent of the Senate, to serve a five-year term. The ombudsman would have experience in auditing, conflict resolution, government relations, investigations, law, or social work.

The ombudsman would be empowered to review agency policies on a wide range of issues, including the use of restrictive housing, plans to close or renovate facilities, the adequacy of mental health care and educational or vocational programs, and more.

In addition, an ombudsman may subpoena an individual to either provide sworn testimony or produce documentary evidence when investigating a complaint.

“If the ombudsman determines that an employee or agency of an agency acted in a manner warranting criminal charges or disciplinary proceedings, the ombudsman shall refer the matter to appropriate authorities,” according to the legislation.

After completing an investigation, the ombudsman would have about 30 days to provide a written report. If the report requests a response from a representative at a correctional facility, an answer would be required within 30 days after report is received.

The ombudsman would submit an annual report to the governor and General Assembly to detail investigations conducted.

The legislation is cross-filed in the Senate and co-sponsored by Sens. Shelly Hettleman (D-Baltimore County) and Chris West (R-Baltimore County). The Senate Judicial Proceedings Committee plans to hold a hearing Feb. 8.

The salary for an ombudsman would be “equal” to a district court judge slightly exceeding $171,300.

In an interview before Tuesday’s hearing, Davis said the attorney general’s office told her one main goal for the legislature to accomplish: “just fund” the position.

Current process

Three administrators with the state Department of Public Safety and Correctional Services testified Tuesday about current department policies and answered questions from the legislative panels, but didn’t speak in favor or against the legislation.

Cleveland Friday, acting assistant commissioner for the department’s eastern region, said after an inmate who files a complaint to a warden, it’s reviewed for no more than 45 days by a commissioner of corrections.

If an inmate wants to appeal the commissioner’s decision, that person has up to 45 days. If the appeal isn’t overturned by the commissioner, an inmate can appeal through a grievance process and the complaint will be heard by a state administrative law judge, Friday said.

He said the state’s Intelligence and Investigation Division has “carte blache” to make unannounced visits to state prisons, including to check on living conditions or the well-being of inmates.

“We do have mechanisms by which unannounced visits can be made at any facility,” he said.

David Greene, a warden who oversees the Dorsey Run Correctional Facility in Jessup, the Baltimore City Correctional Center and the Central Maryland Correctional Facility in Sykesville, approves of the formal process to resolve inmate complaints called an administrative remedy procedure, also called ARP.

“If I see that there are two or three complaints…I know where to direct some extra resources and how to respond to that. If we’re wrong, we’re wrong,” he said. “We attempt to resolve every concern we will be aware of at the lowest level possible as quickly as possible.”

Gordon Pack, who served 42 years in prison after being charged at age 15 for rape, kidnapping and armed robbery, said an ombudsman would help people who are incarcerated and prison employees.

He said some case managers are overworked, which affects those incarcerated from receiving proper medical treatment and other needs.

“It’s a hardship all the way around,” said Pack, 59, of Baltimore City, who was released about 2 1/2 months ago. “I support an ombudsman. It helps everybody.”