This article was republished with permission from WTOP’s news partners at Maryland Matters. Sign up for Maryland Matters’ free email subscription today.

This content was republished with permission from WTOP’s news partners at Maryland Matters. Sign up for Maryland Matters’ free email subscription today.

Maryland state agencies are awash in vacancies, losing seasoned workers and struggling to perform core functions, according to union leaders, members of the General Assembly and Attorney General Brian Frosh.

Critics maintain that Gov. Lawrence J. Hogan Jr. (R) has been at best indifferent to the hollowing out of state government and at worst has precipitated the loss in personnel by failing to offer more competitive salaries and benefits.

“Our state government is grotesquely underfunded now,” said Frosh (D) in an interview. “If there’s a Democratic governor who’s elected [in November] who values government services, that person will find that we’re really hamstrung.”

The state’s empty-desk problem has been well-documented.

According to a four-year review of state issues published last month by the nonpartisan Department of Legislative Services, the state’s vacancy rate in public safety, health and human services agencies jumped from 12.7% in 2018 to 13.8% in 2022.

Some areas of the government with difficult-to fill positions, such as human services (14.7%) and public safety and correctional services (14.1%), had higher than average vacancy rates, the report found.

“A more troublesome trend in State personnel has involved high rates of position vacancies, particularly for correctional officers, information technology-related personnel, physicians, nurses, and selected other position classifications,” analysts concluded.

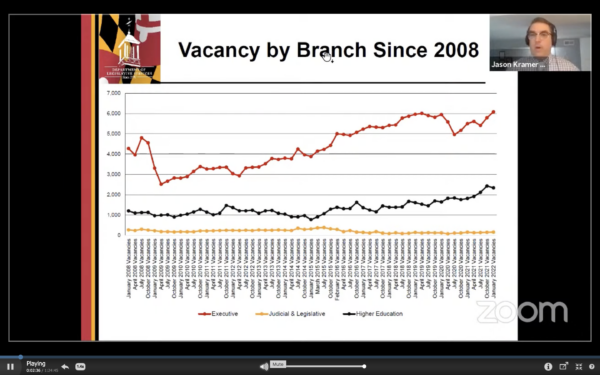

More than 6,000 positions — one-eighth of the government — is unstaffed. “That’s more than there have ever been in our records,” legislative analyst Jason Kramer said. “Vacancy rates are high across state government.”

The problem is compounded, observers say, when you consider that the vacancy rates loom high even as the total number of government worker positions has declined.

“The statewide vacancy rate had grown by nearly 2 percentage points and over 650 positions compared to four years prior, despite eliminating 1,235 regular positions from the State workforce,” the report concluded. “Persistently high and increasing vacancy rates, exacerbated even more by the COVID-19 pandemic, were a noted concern throughout the term.”

At a news conference on Wednesday, union leader Patrick Moran said there are currently more than 7,000 vacant positions and he accused the governor of creating a “manufactured crisis” by under-funding agencies.

“These purposeful cuts and vacancies have resulted in a lack of needed services, skyrocketing overtime to hundreds of millions of dollars, and used as cover to… privatize public services,” said Moran, head of the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees Council 3, which represents 30,000 workers in state government and Maryland’s higher education institutions.

Moran, Rep. Anthony Brown (D), Sen. Cory McCray, Del. Brooke Lierman (D) and union leaders spoke to reporters outside the Charles Hickey School in Baltimore County, a Department of Juvenile Services facility, a site chosen because of what employees called a dire staffing shortage. (Brown, a former lieutenant governor who lost to Hogan in 2014, is running for attorney general; Lierman is running for comptroller.)

“We are dealing with dangerously low staffing levels,” said AFSCME board member Denise Henderson Johnson, who represents Department of Juvenile Services personnel. She said front-line positions stay open 200 days on average before they are filled. “Staff are leaving faster than we can hire and train staff to fill their jobs.”

Those concerned about the state staffing shortages say the impacts on service delivery and government oversight are wide-ranging — delaying unemployment insurance payments, slowing SNAP payments to needy residents, limiting environmental and workplace inspections, and countless other interactions.

In February, the state’s chief medical examiner said staffing shortages caused a backlog in the processing bodies at the state morgue.

Maryland Transit Administrator Holly Arnold told the Board of Public Works on Wednesday that the agency has been forced to reduce train service because of a severe lack of operators.

She told the panel that 26 of 79 light rail operator positions are vacant. “What that means for the riders is unreliable service,” she said. “This service adjustment really allows us to stabilize the service and provide a schedule that riders can rely on.” She said the agency is working “very hard” on training and retention efforts. Arnold said it takes 12 weeks to train a light rail operator.

Although union leaders cast the issue as a lack of competitive wages, some economists and professional hiring managers say the issue is more complex. They point to a lack of skilled employees relative to the number of job openings.

In a statement, Hogan spokesman Michael Ricci said the administration has provided $850 million for bonuses and other salary enhancements, and has reached agreements with all of the unions that represent state employees, “including one with AFSCME just days ago.” The governor’s budget also included $22 million for correctional officer salary enhancements “to help recruit and retain critical staff.”

In March, Hogan announced that the state would no longer require a four-year college degree for a wide range of state jobs. AFSCME pushed back against the reform and accused the governor of “deskilling state services.”

“We are looking for partners in this effort, not hacks,” Ricci said.

Maryland is not alone in its struggle to find workers. Legislative analysts surveyed other states and found that double-digit vacancies are common. Virginia state government, for example, has a 17.6% vacancy rate; Delaware’s is 15%.

Frosh: Impacts are wide-ranging

A state legislator for nearly 30 years before becoming attorney general in 2014, Frosh has interactions with every agency in state government.

He said that without a sufficient number of properly trained inspectors, employers who cheat workers out of overtime and exceed water and air pollution limits have near carte blanche to do anything they want.

Frosh accused Hogan of pursuing an agenda that dates back to the era of Republicans Barry Goldwater and Ronald Reagan. “They think that starving government is a value and the government gets in the way,” he said. “The Republicans have — I don’t want to say won the war — but they’re winning the war.”

Members of the General Assembly held hearings on the staffing problems in state government during their legislative session this year. Budget Secretary David Brinkley acknowledged the challenge Maryland has had in filling vacancies, but said the problem flows from a variety of factors, including the aging of the Baby Boom generation, the pandemic and the “Great Resignation.”

“The state’s current high vacancy rates are a reflection of a national hiring crisis and not an accurate reflection of the state’s efforts to recruit and retain employees,” he said. “Over the past two years, we have aggressively pursued compensation increases, work/life balance enhancements, administrative streamlining and rebranding to retain employees and recruit additional ones.”

But in an interview, House Majority Leader Eric Luedtke (D-Montgomery) said there is a “clear pattern” of experienced state workers leaving and not being replaced that predates the pandemic. “You see it in virtually every state agency,” he said.

Luedtke said business owners, for example, are much more likely to hear about incentive programs from local economic development officials than they are from the state Department of Commerce. “I just don’t think they’re very good managers of state government.”

At a hearing on the staffing shortage in January, lawmakers were told that vacancies result in increased caseloads on other workers, sap the state of seasoned personnel, create additional hiring and training costs due to “churn,” and force the state to spend more on overtime.

State government suffers from a mountain of unfilled positions in part because the salaries it offers aren’t competitive, Frosh and Moran said.

The attorney general said promising young attorneys have declined job offers because county governments and the City of Baltimore pay more. He said even nonprofits now routinely offer better pay. Moran said that when it comes to corrections officers, the state has effectively become the training ground for local government.

“No one’s going to go to work in those jobs for those wages. That’s the reality,” he said. “I can go to work as a correctional officer in the county and I can make more money and I can get a better pension — and it’s not as dangerous.”

Like Frosh, Moran said there aren’t nearly enough inspectors making sure that construction companies are following the law on prevailing wages — making sure that workers get the pay and overtime they’ve earned.

“Hogan doesn’t believe in regulations. He doesn’t believe in making sure people are paid properly,” Moran said. “He doesn’t concern himself with working poor people.”

At her last Board of Public Works meeting in December, Treasurer Nancy Kopp (D) warned Hogan and Comptroller Peter Franchot (D) about the loss of talent and surfeit of empty desks. It has “always” been “a serious issue,” she cautioned, but now is “reaching a critical stage.”

Moran called on the next governor and General Assembly to fill 95% of the positions that are currently vacant.

Editor’s Note: This story was updated to include a comment from the governor’s office.