This article was republished with permission from WTOP’s news partners at Maryland Matters. Sign up for Maryland Matters’ free email subscription today.

This content was republished with permission from WTOP’s news partners at Maryland Matters. Sign up for Maryland Matters’ free email subscription today.

Restaurants and other businesses that have survived more than two years of COVID-19 restrictions could see an infusion of federal dollars in the coming months, as long as U.S. lawmakers reach final agreement on a multibillion-dollar package.

The U.S. House has approved a bill with $42 billion for restaurants and $13 billion for a hard-hit industries program that would help small businesses that weren’t eligible for restaurant aid.

That legislation, however, only got the backing of six House Republicans, signaling it doesn’t have the support necessary in the evenly divided U.S. Senate to make it to President Joe Biden’s desk.

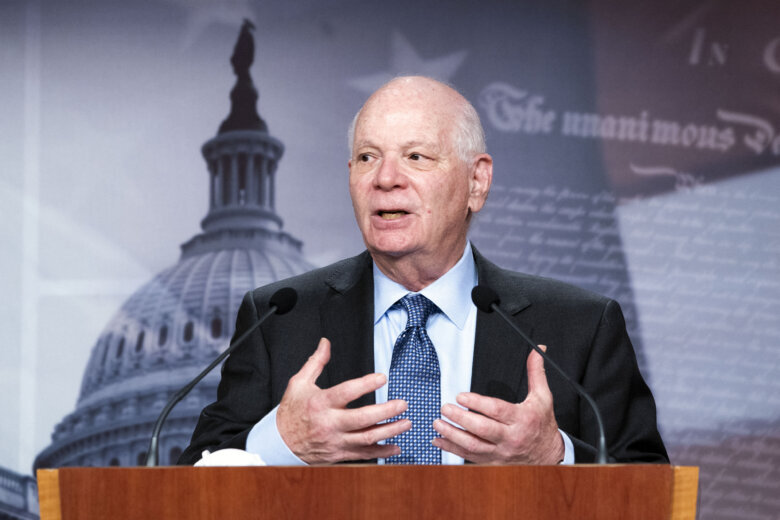

That’s where Maryland Democratic Sen. Ben Cardin and Mississippi GOP Sen. Roger Wicker stepped in with their own bill to provide $40 billion to restaurants and $8 billion to various small businesses.

“We’re looking at any way to move this as soon as we possibly can, because it’s pretty desperate,” Cardin said during a brief interview.

Aside from the $2 billion gap in funding for restaurants, the biggest differences between the bills is how to provide money for non-restaurant businesses and how to pay for the legislation.

The House bill would create one pot of $13 billion for businesses with 200 or fewer employees that experienced a pandemic-related revenue loss of 40 percent or more. Businesses would be eligible for up to $1 million each.

The Senate bill from Cardin and Wicker would create separate pots of money for various businesses.

Two billion dollars would be available for gyms that lost more than 25% of their revenue; $2 billion would be divided up to live event venues that lost more than 25% of their revenue; $2 billion would be allocated to buses and ferries, including charter buses, commuter buses, school buses and passenger ferries; $1.415 billion would be doled out to very small businesses located near land border crossings that were closed during the pandemic; and $500 million would go to minor league sports teams that lost at least 50% of their revenue.

An additional $75 million would go to small businesses in Alaska that were completely cut off from the rest of the country during the pandemic after borders closed. And there would be $10 million for small businesses in similar communities in Minnesota and Washington states.

“Congress took action to provide much needed relief to restaurants and other businesses during the height of the pandemic, but the initial program left thousands of eligible restaurants and their employees without any assistance,” Wicker said in a statement. “As our economy recovers from a difficult two years, it is important to replenish this fund as a matter of fairness.”

The restaurant funding would go to the Restaurant Revitalization Fund that Democrats established last year in their $1.9 trillion COVID-19 relief package.

Democratic lawmakers originally approved $28.6 billion, but more than $76 billion in requests quickly outpaced the amount of money the Small Business Administration had to send struggling restaurants. About two-thirds of restaurants that applied to the program didn’t receive funding.

That led several organizations to call on Congress to provide more aid to help restaurants cover bills from payroll, operating expenses and construction costs for outdoor seating areas.

Mike Whatley, vice president of State Affairs and Grassroots Advocacy at the National Restaurant Association, said some restaurants getting aid while others didn’t “created an uneven playing field.”

“These restaurants did nothing wrong. They applied, they filled out their paperwork, they were qualified and then ultimately the aid didn’t come,” Whatley said.

Concerns that additional federal spending on COVID-19 relief could further exacerbate record-breaking inflation don’t necessarily apply to the Restaurant Revitalization Fund, he said.

Many of the restaurants seeking aid, Whatley said, plan to use federal dollars to pay down bills and other debts.

“We believe that for restaurants and the RRF, this should be bigger than politics, this should be a bipartisan issue and Congress should figure it out and get it done to make up the gap,” he said.

Several lawmakers have pushed back on additional pandemic spending, citing inflation and lower COVID-19 cases throughout the country.

Restaurants continue to face pandemic restrictions, Whatley said, noting that Philadelphia is reinstating its mask mandate and new variants are expected to crop up.

“We are without a doubt in a much better place than we were two years ago, or even a year ago, in terms of the COVID environment. But it’s still harming restaurants,” Whatley said.

Without additional aid from Congress, 80% of restaurants that didn’t get funding from the RRF are at risk of permanently closing, according to a survey from The Independent Restaurant Coalition.

U.S. House debate on its bill, which passed following a 223-203 vote on Thursday, largely centered around Republican concerns over inflation and frustrations with how the Small Business Administration has handled programs in the past.

Rep. Blaine Luetkemeyer, a Missouri Republican, argued the bill was “a disingenuous attempt to posture to small businesses.”

“At this time, small businesses need the freedom to operate independently without Washington watching over them,” he said. “We must end the COVID economy of government handouts.”

Luetkemeyer also rebuked Democrats for proposing to pay for the House bill by recovering funds from people who fraudulently acquired them from prior aid programs.

“I agree that we need to track down and hold fraudsters accountable, and I applaud that process,” Luetkemeyer said. “But this process takes time, and it is not going to get all those dollars back.”

House Majority Leader Steny Hoyer, a Maryland Democrat, said the legislation is about “economic resilience.”

“You can’t be independent if you go bankrupt,” Hoyer said. “You can’t be independent if you can’t operate your business.”