This article was republished with permission from WTOP’s news partners at Maryland Matters. Sign up for Maryland Matters’ free email subscription today.

This article was written by WTOP’s news partners at Maryland Matters and republished with permission. Sign up for Maryland Matters’ free email subscription today.

Officials from a Caroline County town have hired an independent firm to investigate the role Ridgely Police Chief Gary Manos played in the deadly pursuit of Anton Black after Maryland State Police denied a request to review the matter.

It’s the latest development in the fallout from the teenager’s death last fall on the Eastern Shore.

Ridgely officials made the request – to examine whether Manos followed departmental guidelines – in March, according to Major Greg Shipley, a State Police spokesman.

“The Maryland State Police declined to initiate an administrative investigation for several reasons,” Shipley said. “They included the fact that six months had passed since the death of Anton Black, our criminal investigation was already concluded and our administrative investigation involving the Greensboro Police Department was already underway.”

Shipley said the State Police suggested Ridgely hire an independent entity not involved in the agency investigations to conduct a review.

At the time of Ridgely’s request, the State Police were conducting an “internal administrative investigation” of another cop involved in the case, Greensboro Police Officer Thomas Webster IV, to determine if he properly followed departmental guidelines when Black died after being in police custody last September. Webster was the first police officer to come in contact with Black after a 911 caller reported a possible child abduction in the town.

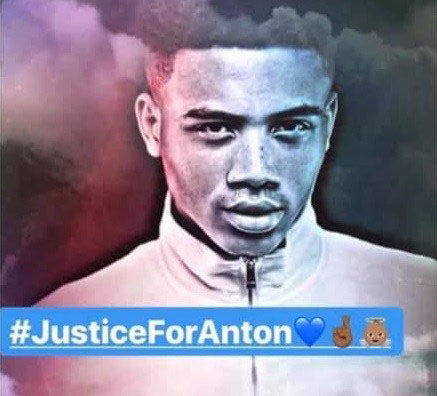

Black, a 19-year-old African American Caroline County resident, died Sept.15 in Greensboro. The State Police formally closed their criminal investigation of Manos, Webster, Centerville Police Officer Dennis Lannon and a civilian who aided police, on March 7. The Caroline County state’s attorney declined to seek indictments in the matter.

While the State Police have not completed their review of Webster, Greensboro’s newly hired police chief, Eric Lee, placed Webster on temporary leave April 20. While Webster will still receive pay, he will no longer report to the police station for administrative duties. He was placed on administrative duty in January by the former Greensboro Police chief.

“It was a mutual agreement that he and I made in the best interest of the town,” Lee said. “It wasn’t punitive at all.”

On April 1, the town of Ridgely hired Greenbelt-based law firm McNamee Hosea to conduct an administrative review of Manos similar to the one that state police are conducting of Webster.

“In the interest of due diligence, and for that reason alone, the Town has engaged the law firm of McNamee, Hosea, Jernigan, Kim, Greenan & Lynch to conduct an independent investigation into whether the Chief complied with the Town Police Department’s General Orders in connection with the events of September 15, 2018,” a Ridgely Town spokeswoman said in a statement. “The Commissioners feel strongly about assuring the residents of Ridgely and the greater community that every opportunity has been taken to ensure this matter was thoroughly vetted.”

Rene Swafford, an attorney for the Black family, said they were informed that the firm was hired on May 6, when they attended the Ridgely Town Commission meeting to request Manos be placed on administrative leave.

Swafford said two weeks earlier she had provided Ridgely officials with letters and statements alleging Manos had altered the body camera footage that Webster wore the night Black died.

Based on the body camera footage, Manos appears to have had the most physical contact with Black. He can be seen covering part of Black’s body for an extended period of time while other officers placed handcuffs and leg restraints on Black.

Black died of sudden cardiac death Sept. 15 after Webster, Manos, Lannon and Greensboro resident Kevin Clark chased Black to his mother’s front door following a 911 call reporting a possible child abduction. After a struggle with Manos, the men – all white — held Black down and placed him in handcuffs. With the aid of a fourth and fifth officer, leg shackles were applied — at which point Black became unconscious and then went into cardiac arrest.

Black had recently been diagnosed with a mental health disorder and was reportedly experiencing a mental health episode at the time of the alleged abduction. A 911 caller reported a younger boy being dragged down the street against his will. The boy turned out to be distantly related to Black; the two had known each other for years.

But in an interview in January, the boy, 12, said he was frightened. Black had been talking to himself, calling the boy his brother’s name and acting aggressively. When Webster first came in contact with Black, the boy told him he was schizophrenic.

Now that Webster is on administrative leave and no longer reporting to work at the Greensboro Police Department, he is receiving financial compensation as a police officer from both Maryland and Delaware law enforcement agencies. In 2016 he separated fromthe Dover, Del., Police Department after he was indicted on second-degree assault charges related to an African American suspect in his custody.

A Maryland licensing agency that certifies police officers is considering withdrawing Webster’s credentials to work as a police officer in the state.

In the meantime, Lee, the new Greensboro police chief, said he hopes to work closely with the community and rebuild trust that is missing – though he has not yet introduced himself to the Black family.

“I firmly believe this is a community police department,” Lee said. “And I have the pleasure of serving the community.”

Lee said handcuffs will be used as a last resort, de-escalation techniques will be emphasized, and all officers will become certified and fully trained in “crisis-intervention training.”

“It isn’t required, but I will treat it as if it is,” Lee said.