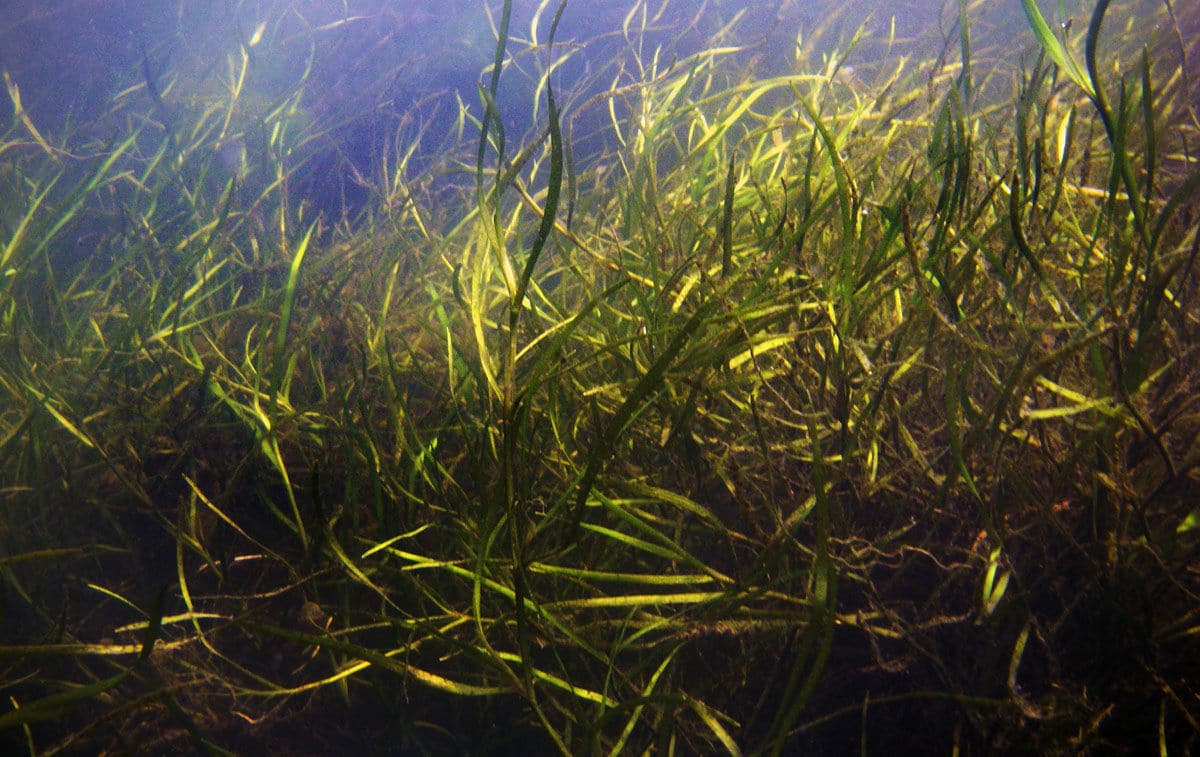

WASHINGTON — Underwater grasses along the bottom of the Chesapeake Bay that had been virtually wiped out by pollution decades ago have made a remarkable comeback, according to new research from the University of Maryland.

The resurgence of aquatic grasses signals a positive shift in the ecological health of the bay and provides fresh evidence that long-term cleanup efforts in North America’s largest estuary are paying off, the university’s Center for Environmental Science said.

“The Chesapeake Bay has turned the corner. In fact, it’s one of the large ecosystems in the world that has probably made the most progress,” said Peter Goodwin, president of the center, in a statement.

The center attributes the resurgence to specific efforts to reduce what’s known as nutrient pollution — essentially an overdose of nitrogen and phosphorus from wastewater and runoff that enters coastal waters. The nutrients fuel the growth of algae on the water’s surface, which blocks sunlight from reaching the bay grasses below.

Researchers analyzed 30 years of data on land use, fertilizer application and land runoff in the Chesapeake Bay area. Since 1984, nitrogen concentrations in the water have fallen by 23 percent and phosphorus concentrations by 8 percent, thanks to long-term efforts by federal, state and local agencies to reduce nutrient pollution in the bay.

The study was published March 5 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Aquatic grass is considered ecologically important because it provides a habitat for baby crabs and other creatures, protects shorelines and reduces erosion.

The underwater vegetation is also what’s known as a sentinel species — a natural early warning system of ecological damage.

“We’re been calling these grasses our coastal canaries, the things that are most sensitive to water quality degradation, and the things we have to watch as long-term indicators of these water quality situations,” said Bill Dennison, vice president of the environmental science center.

Still, the Chesapeake Bay still has room to improve. Last spring, the center released its annual report card on the bay’s overall ecological health, which assessed a C grade. That’s up from failing grades for several years.