COLLEGE PARK, Md. — In 2012, a drunken driver struck and killed 22-year-old Matthew Cheswick on Memorial Day weekend as he walked on Coastal Highway in Ocean City, Maryland, a popular tourist destination on the Atlantic coast.

The Towson University student was one of 40 people hit by vehicles on the state highway that year, and one of two deaths.

In response, the Maryland State Highway Administration ran a pedestrian education campaign with the city that featured a cartoon crab named “Cheswick” in his honor. They also installed a mid-block pedestrian walk signal in 2014 near the spot Cheswick was killed.

A project to improve lighting and install a 2 miles-long median fence along Coastal Highway is scheduled to be completed before the 2018 tourism season.

“I have to give it to [the transportation agencies],” Cheswick’s mother, Cecilia Roe, said. “They have been wonderful.”

But improvements have progressed more slowly elsewhere across Maryland.

Sections of Branch Avenue and Curtis Lane, in the low-income area surrounding the Naylor Road Metro station in Hillcrest Heights, have been slated for pedestrian and biking improvements in each year’s capital projects plan since 2012.

While awaiting completion of the project, at least 24 pedestrians have been hit on Branch Avenue and other state roads within two miles of the station since 2015.

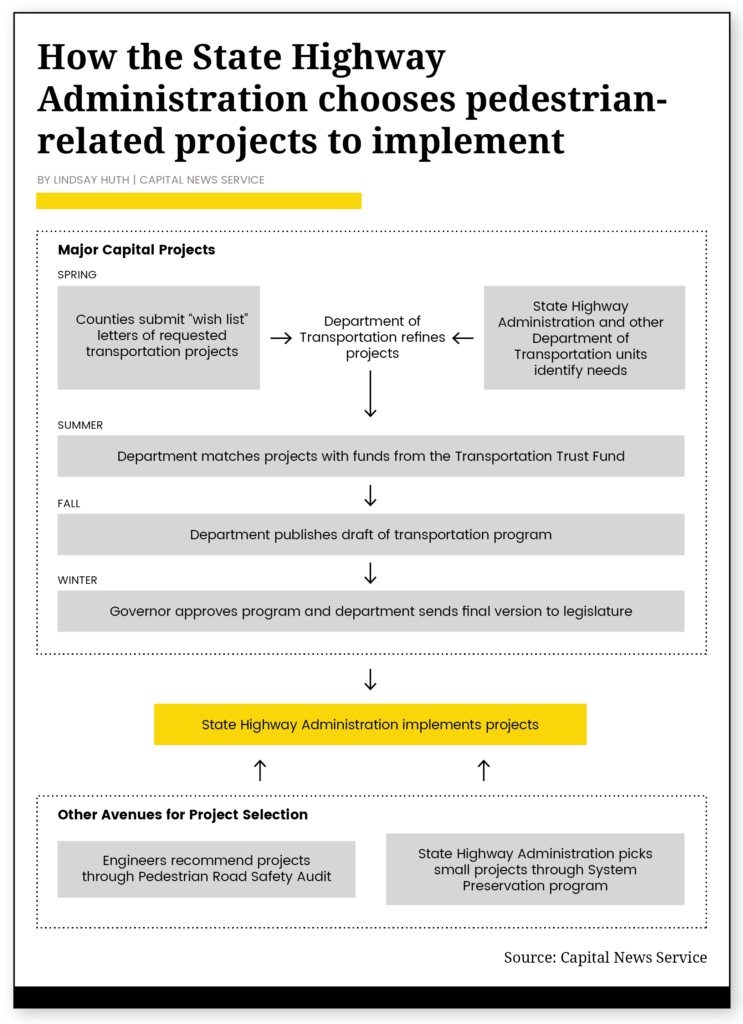

The Maryland Department of Transportation funds major state road construction projects through the Consolidated Transportation Program, the department’s six-year capital projects plan. It picks which projects to include based in part on annual priority letters submitted by counties with the governor and legislature’s approval.

The county priority lists are dominated by car-focused projects — such as reducing traffic congestion on Interstate 270 in Montgomery County and improving car access to the Greenbelt Metro in Prince George’s County. Both counties placed pedestrian safety improvements near the bottom of their letters.

“Although not specifically included in the attached list, Prince George’s County believes it is imperative that the state address the lack of safety features included on and along state-maintained roadways,” the Prince George’s County 2013 letter read.

Montgomery County specified Georgia Avenue as one of its “highest need” locations for pedestrian improvements. But that too was mentioned near the bottom of its priority list, below major car-related projects.

The SHA rarely undertakes capital projects dedicated solely to major pedestrian improvements along roadways. But Charlie Gischlar, the agency’s media relations manager, said the state looks for ways to include pedestrian safety improvements in most major road projects.

“When we make a road improvement, let’s say to break congestion, we also will put in, usually most of the time, sidewalk or a bike lane or something of that nature,” Gischlar said.

Making the list doesn’t assure swift action.

Like Georgia Avenue in Wheaton, Branch Avenue experiences the heavy pedestrian traffic that comes with a Metro station. The fading crosswalk in front of the Naylor Metro had no functioning pedestrian signals when Capital News Service visited in October.

Sidewalks were crumbling or missing entirely. Pedestrians have worn dirt paths in the grass along the southern side of the station because sidewalks are only accessible from the north. Some restaurants and businesses pedestrians pass along Branch Avenue to get to the station have no sidewalks, forcing pedestrians to cut through parking lots along the edge of the six-lane highway.

Gischlar said the agency is adding sidewalks along those parking lots, replacing and widening others and repainting crosswalks, but completion has been delayed while the agency redesigns the project to address drainage and other problems. He said work will restart next year.

But while the drainage pipes are replaced, no sidewalks are available across the street from the Metro station.

SHA-funded pedestrian safety improvements

The SHA also can select and fund pedestrian safety improvements through the System Preservation Program.

The agency established the Pedestrian Road Safety Audit in 2012 to identify areas with high numbers of pedestrian crashes, said SHA education and marketing manager Lora Rakowski. The audit is “one of the biggest tools we have” to address pedestrian crash areas, according to Anyesha Mookherjee, deputy director of SHA’s Office of Traffic and Safety.

Engineers compile a list of one-mile sections of state roads where 10 or more pedestrian crashes occurred in a five-year period, ranked by the number of accidents.

“There is no real statistical reasoning behind why we chose 10 and not eight or, for that matter, one,” Gischlar said.

The 10-accident threshold was based on “engineering judgment,” said Mookherjee. “Whichever has the highest [number] of crashes, we get to it first.”

To conduct the audit, the agency forms a multidisciplinary group of engineers, fire and EMS officials, and community members to look into the areas, Mookherjee said.

Small-scale improvements can be implemented in 30 to 90 days, while larger projects may take one or two years, or longer, Mookherjee said. Many of SHA’s seven district offices can pay for the smaller improvements within their jurisdiction themselves. Larger ones are often funded in stages, from design through construction, and officials ask for components of the project, such as a new traffic signal, from the statewide budget.

At many locations, the agency has completed its short-term projects, but long-term ones are still in progress. These audits led to the extended walk light in Wheaton and the pedestrian walk signals, lower speed limit, pedestrian walkways and median fence in Ocean City, Gischlar said.

But the agency denied a records request to obtain the audit results, saying releasing the records would be against the public interest because it “could be used to attempt to discover MDOT SHA’s thought process regarding decisions affecting highway safety.”

Rakowski provided a list of 22 roads identified through the audit, but provided no accident statistics or what improvements, if any, were made.

SHA also investigates the site of every fatal crash, Gischlar said.

“So, we’ll go out and take a look if there’s anything we can do right off the bat, trim branches to improve sight distance, maybe freshen up on some pedestrian pavement markings,” he said.

SHA investigates “pretty much everything” citizens or counties bring to its attention, Mookherjee said. “Any concern they [citizens] have, we will have an engineering study.”

SHA uses a 1,000-page book called the Maryland Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices, or MUTCD, to assess whether additions such as crosswalks or pedestrian signals are warranted at a particular location.

“That pretty much is the Bible of traffic engineers,” Mookherjee said.

Sean Emerson, an activist with the Action Committee for Transit in Montgomery County, said SHA responds to most requests for pedestrian improvements by citing the MUTCD passage that says it’s not necessary.

For the SHA to OK the painting of a new crosswalk, the section of road in question must meet all of the criteria outlined in MUTCD, said Emerson, a legislative aide to Bethesda state Del. Marc Korman.

“The SHA will come back and say, ‘Sorry, it’s not warranted,’” Emerson said.

Rather than making engineering changes, the state often handles high-crash areas through driver and pedestrian education initiatives, such as its “Look Up, Look Out” campaign and the Maryland Department of Transportation’s “Toward Zero Deaths” pedestrian safety page, which features tips such as “Watch for turning vehicles” and “Use pedestrian pushbuttons.”