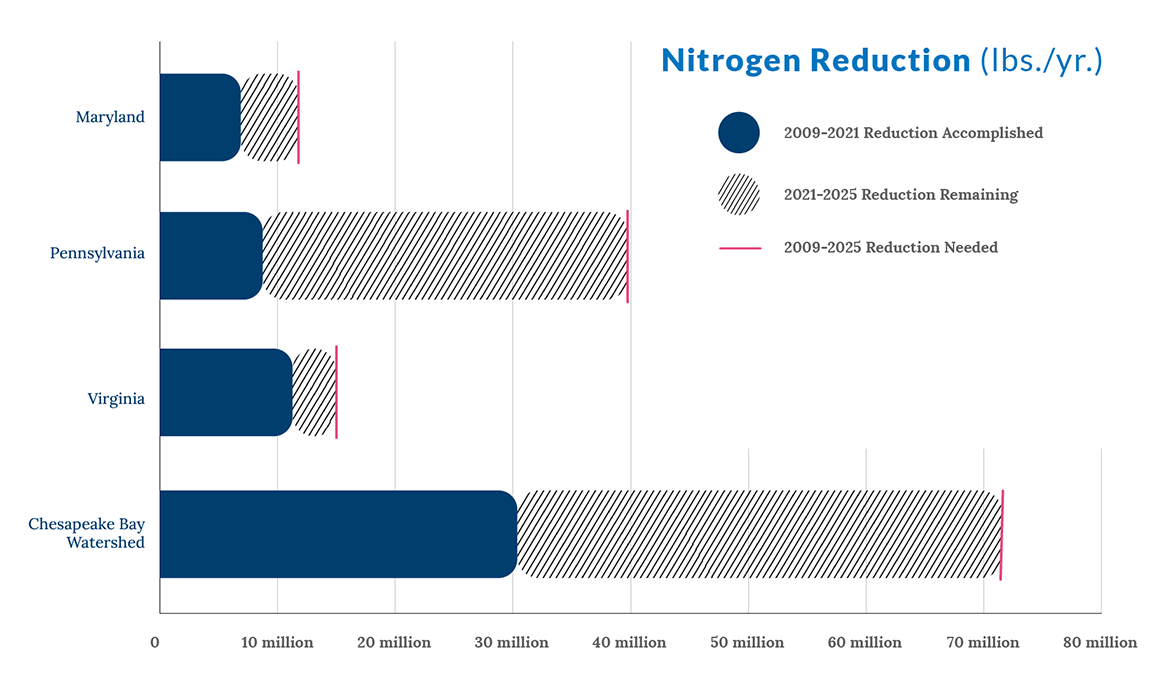

The bay states of Maryland, Virginia and Pennsylvania are collectively not on track to restore the Chesapeake Bay to healthy levels by 2025; but individually, Maryland and Virginia may make it.

That’s according to the 2022 State of the Blueprint report released Wednesday by the Chesapeake Bay Foundation. The three states account for some 90% of the pollution on the bay.

“While the Bay states collectively are not on track to meet the Blueprint’s 2025 implementation deadline, the partnership must build on lessons learned, achieve the Blueprint commitments as quickly as possible, and maintain the limits long-term,” Chesapeake Bay Foundation President Hilary Harp Falk said in a statement.

Much of this progress is due to reducing pollution from wastewater treatment plants. Wastewater treatment upgrades are the key reason Maryland and Virginia, individually, may still meet their goals by 2025.

The Chesapeake Bay Executive Council, which leads the restoration efforts, will meet next week, and it is scheduled to take action to continue the restoration progress. The council is also expected to recommit to the partnership and promise to develop a new plan with a specific timeline and accountability, a foundation news release said.

Since the Chesapeake Clean Water Blueprint’s establishment in 2010, the states have had practices in place with the aim of some 42% of nitrogen pollution reductions and 64% of phosphorus reductions.

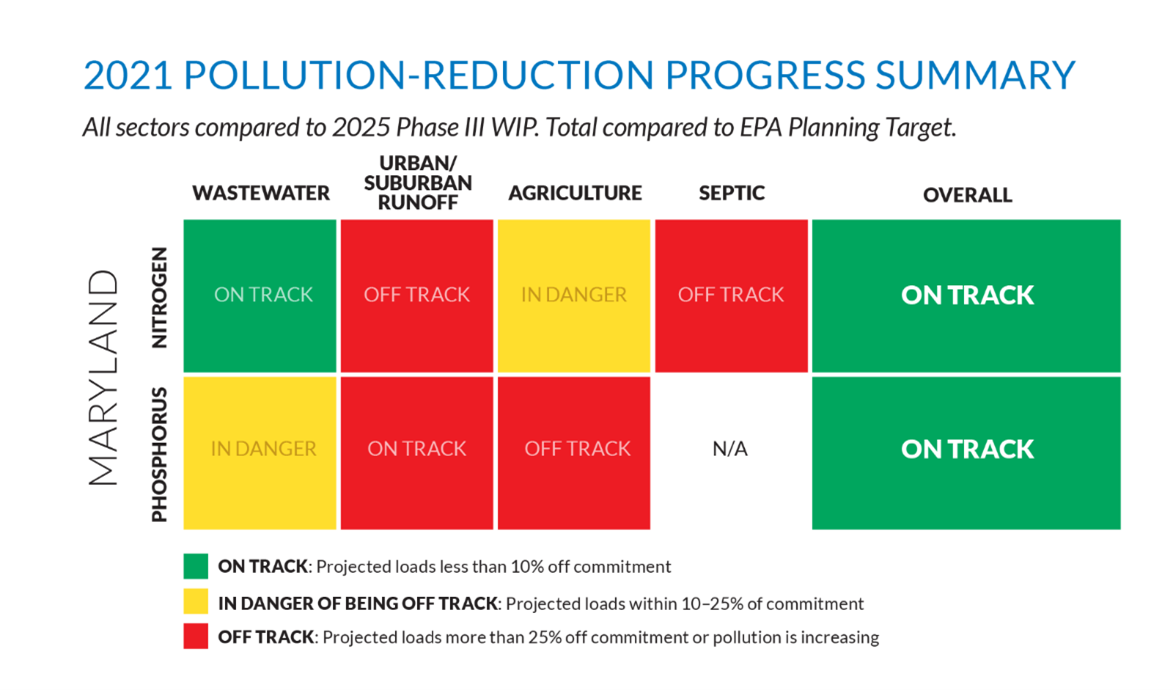

How Maryland is doing

Maryland is depending on pollution reductions from wastewater treatment plants to offset pollution from other sources in order to meet the Blueprint goals, Chesapeake Bay Foundation Maryland Executive Director Josh Kurtz said in a statement.

The report said that reductions from direct pollution sources must be maintained, while leaders focus on reducing urban and agricultural runoff, which are currently the two largest sources of bay pollution in Maryland.

“We recommend the state tighten its permit standards for city and county stormwater systems to reduce runoff from developed areas,” Kurtz said. He also added the need for stronger protections for trees and forests, and more help for farmers on more “natural ways to farm.”

How Virginia is doing

“While Virginia has made meaningful progress, the vast majority of pollution cut so far has come from wastewater plants. That approach is not sustainable. About 90 percent of Virginia’s remaining pollution reductions must come from agriculture, and population growth and climate change are leading to more polluted runoff from developed areas,” the foundation’s Virginia executive director Peggy Sanner said.

In addition to the maintenance of funding levels, the money should be targeted to the “most beneficial pollution-reduction practices, such as planting streamside forest buffers,” in order to meet the 2025 deadline.

While the report commends legislation and investments — such as the Enhanced Nutrient Removal Certainty Act that was recently passed, and the Stormwater Local Assistance Fund that helps pay for reducing polluted runoff — the report said that Virginia is behind on reissuing Municipal Separate Storm Sewer System (MS4) permits.

“Under these permits, the MS4 owner/operator must implement a collective series of programs to reduce the discharge of pollutants from the given storm sewer system to the maximum extent practicable in a manner that protects the water quality of nearby streams, rivers, wetlands and bays,” according to the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality website.

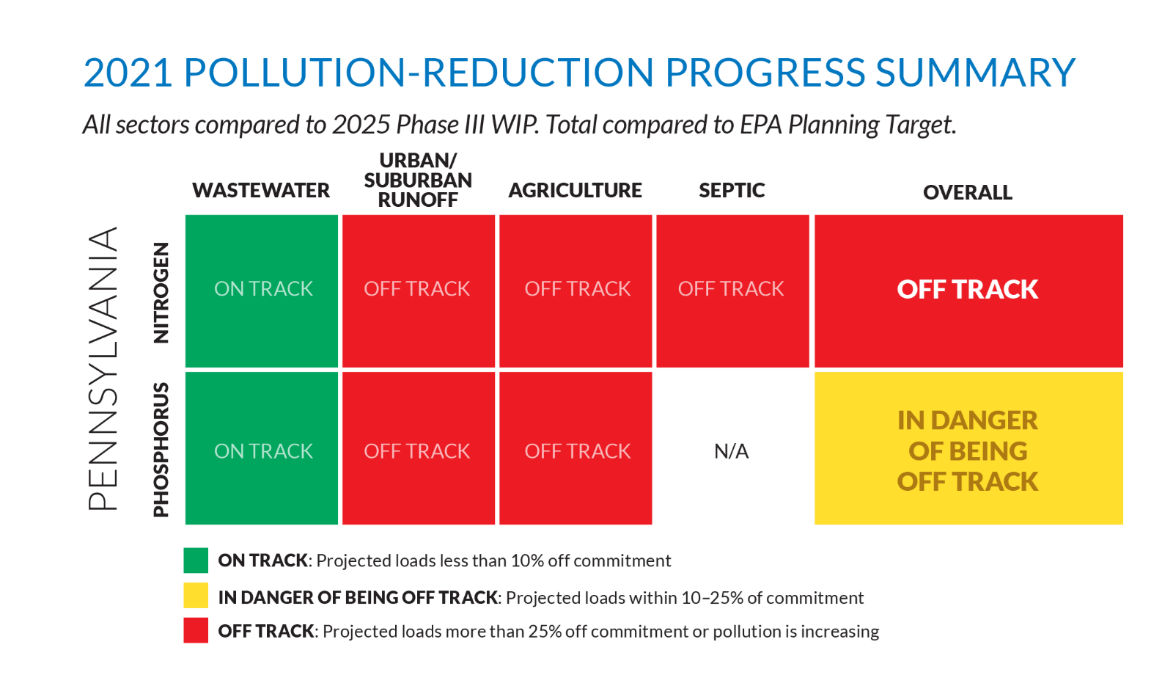

Pennsylvania is not on track to meet its goal

The report found that Pennsylvania is not on track to meet its 2025 pollution-reduction commitments, including the creation of an adequate plan that achieves those commitments.

In 2020, the Chesapeake Bay Foundation said that Pennsylvania was not doing enough to reduce the amount of pollution that’s flowing into the bay from the state’s farms, The Associated Press reported.

Last April, the Environmental Protection Agency said that Pennsylvania’s plan to help clean up the Chesapeake Bay only meets 70% of its goal to reduce its release of nitrogen. The agency said the main source of nitrogen in the state is uncontrolled manure runoff.

The State of the Blueprint report, however, pointed to the momentum of the Keystone State’s $220 million Clean Streams Fund, which includes the new Agricultural Conservation Assistance Program.

“Moreover, counties across the Bay watershed have developed action plans to reduce pollution, creating a strong sense of optimism and commitment from local officials, landowners, and others,” the report said.