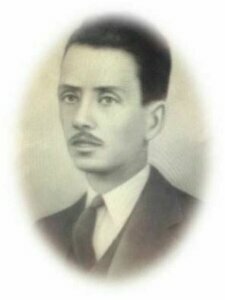

John Samuel Thomas worked on the grounds of the Virginia Theological Seminary during a time of segregation and Jim Crow. His granddaughter describes what it feels like to receive payment for the labor of her ancestor and to study in its hallowed halls.

“It’s really not even describable,” Linda Johnson Thomas said. “There’s a wrong that’s being made right in some sort of way.”

VTS has recently started sending checks to the descendants of enslaved people and other African Americans who were forced to work for little or no pay on the campus over the last two centuries.

According to Johnson Thomas, her grandfather was documented as a supervisor of the janitors at the seminary and later became a laborer at the theological high school.

“While we know that there is no payment for the atrocity of enslaved African Americans, of the brutality that we experienced, there is no amount of money to pay for that, I am still very glad to see that Virginia Theological Seminary has put money where their mouth is,” Johnson Thomas said.

When her grandfather was working on the campus, he wanted to become a Baptist minister. But he couldn’t study at VTS, as Blacks were not allowed to study on campus until 1951. So he took another route to become a minister in D.C.

The religious path is one that Johnson Thomas also followed.

She is the associate pastor at First Baptist Church of Glenarden. In addition to the reparations check she received, she was also invited to do her doctoral studies on the campus.

“My grandfather was not able to study in a place, 70-some-plus years ago, and here I am, on the grounds, studying in the library there at Virginia Theological Seminary,” Johnson Thomas said.

As for the $2,100 check she received, she said she is putting it away for future generations in her family to be able to enjoy the education their ancestors couldn’t.

“When we talk about reparations, true reparations is the ability to help empower people who were disempowered. One of those ways, of course, is through the educational system,” Johnson Thomas said.

She also says there is more she would like to see VTS do to right the wrong done to African Americans in the past.

“When I look across the street from the seminary, my grandparents were on 2 acres of land. That’s not the case today. Property was taken in, as they called it ‘revitalization,’ but in essence, we lost a lot of property there,” Johnson Thomas said.

The VTS reparations program started in 2019, when the seminary announced that it had set aside an endowment of $1.7 million to fund annual payments to descendants of those who worked the grounds.

“For the last almost two years, the research has been going on, and we have found about 35 people who are, what we would term shareholders, meaning they are direct descendants of a person who worked here between the years of 1823 and 1951 be it enslaved or free,” Ebonee Davis, associate for Programming and Historical Research for Reparations at Virginia Theological Seminary, said.

A task force is continuing to search for more descendants.

“I can’t even begin to kind of speculate what that number will be,” Davis said. “But we are anticipating that the number of enslaved people and or free Black people who worked here to sustain this type of institution is in the hundreds, 300 to 400. If you just kind of imagine what their descendants would look like, that number grows quite a bit.”

Every year, the yield of the endowment will be divided among the shareholders they have been able to find.

Over a dozen payments have gone out so far. Those first checks were $2,100.

Across the U.S., many universities, including Georgetown University in D.C. and several Virginia schools, are grappling with their history of using the labor of enslaved people.