How much trash do we throw away? How does recycling work? What, even, is compost? TRASHED is a three-part series that looks at the state of waste in the D.C. region and the options local experts are exploring to cut down on the amount of trash that’s piling up.

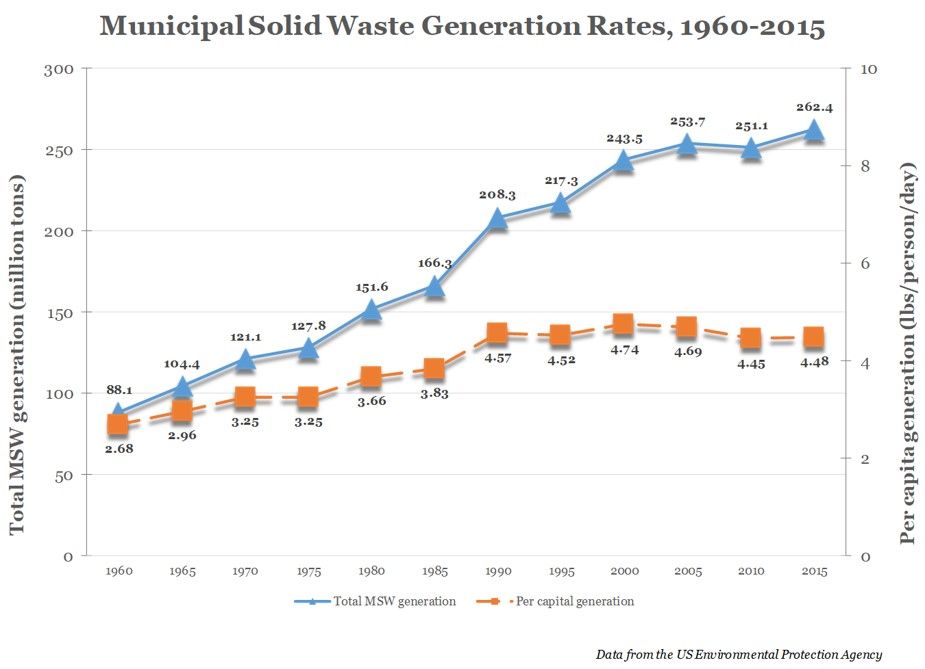

A paper coffee cup in the morning, a plastic-wrapped sandwich in the afternoon and a cold can of something fizzy to end the day: These daily indulgences seem harmless — but they add up. The average American tosses out 4.48 pounds of trash each day.

The United States is hurtling toward a waste crisis. The latest data, from 2015, show Americans produced 262.4 million tons of municipal solid waste that year — the weight of 718 Empire State Buildings — and sent more than half of it to the landfill.

That’s 19 million tons more trash than the U.S. generated in 2000, and 174.3 million tons more than in 1960, according to data from the Environmental Protection Agency.

These numbers are forcing states, cities and counties throughout the country to rethink the way we deal with what we discard. In this three-part series, we’ll look at the state of waste in the D.C. region and the options local experts are exploring to cut down on the amount of trash that’s piling up.

Recycling isn’t exactly thriving in the nation’s capital. D.C.’s waste diversion rate (the percentage of waste diverted from the landfill or incinerator by recycling or other efforts) hovers around 23%. San Francisco’s rate is 80%, and Portland, Oregon, diverts 70% of its waste. New York and Philadelphia’s rates, however, are more in line with D.C.

“[D.C. is] below the national average; it’s below our partners in the region,” said D.C. Council member Mary Cheh, who serves as the chair of the Committee on Transportation and the Environment.

Montgomery County, Maryland, reports a waste diversion rate of 62%; Arlington, Virginia’s reported rate is 49%.

“It’s been hard going; I’ll admit that. And we need to do a better job,” Cheh added.

Neil Seldman still remembers the fight to get recycling up and running in the nation’s capital — and it was all citizen-led. In the 1970s, he and a handful of residents opened recycling drop-off centers in D.C.’s Mount Pleasant, Adams Morgan and Dupont Circle neighborhoods. A bin on 23rd Street in Northwest, near George Washington University, collected aluminum and newspaper.

“And this pattern happened all across the country — people spontaneously started drop-off centers … and then citizen groups got together to start collection, and then they were successful and the cities or counties took them over,” said Seldman, co-founder of the Institute for Local Self-Reliance, a nonprofit that helps communities establish sustainable environmental and business solutions.

Environmentalists brought their recyclables to these sites; they also took their bottles and cans to the front lawn of then-Mayor Marion Barry’s house to protest for a city-wide program. In the ’80s, curbside recycling was introduced in D.C.

So what’s keeping the District’s waste diversion rate so low, decades after recycling started? Experts point to a number of factors.

Cleaning up the recycling system

These days, Annie White has a lot on her plate. The sustainability expert oversees D.C.’s Office of Waste Diversion, which has a goal to achieve at least an 80% waste diversion rate by 2032.

“It’s a lofty goal,” White said. “And it will require every tool in the toolkit to reach it.”

One such tool is consumer education, which D.C. Department of Public Works Acting Director Christopher Geldart said is “really nonstop” when it comes to recycling.

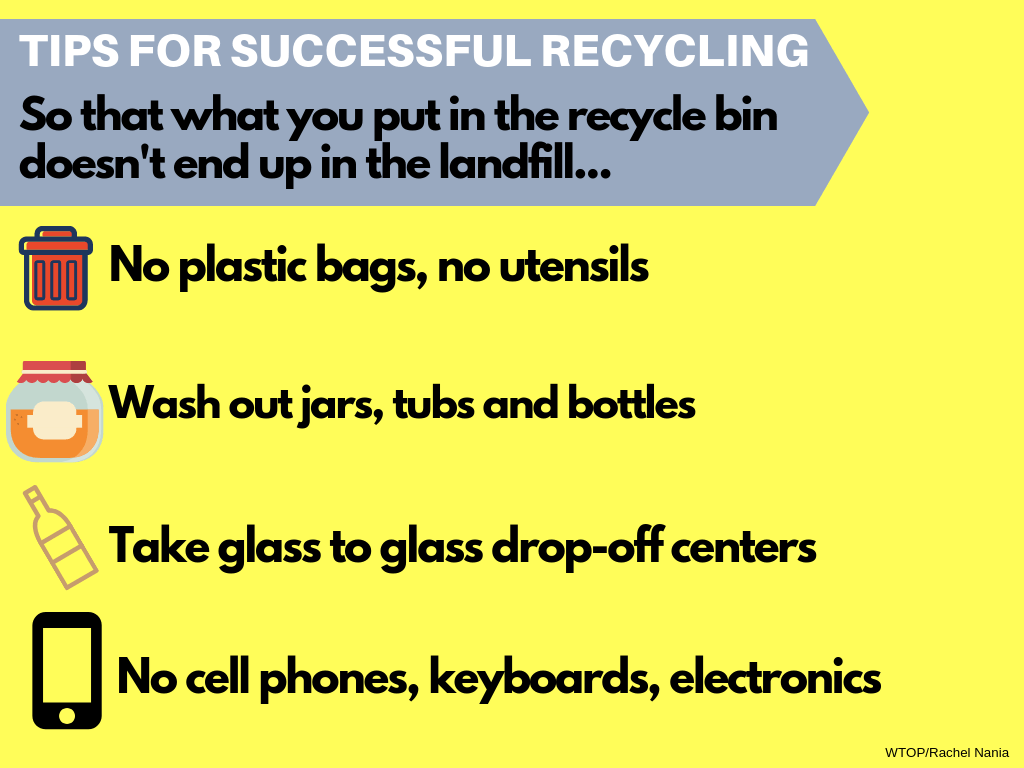

In D.C., and the area more generally, getting the word out about what can and can’t be recycled is a big focus. That’s because most jurisdictions in the region run a “single-stream” recycle program, where everything is collected in one bin before it’s hauled off to be sorted, baled and sold. And a few bad items in the bin can spoil the whole thing.

Straight to the landfill

At a sorting center in Manassas, Virginia, employees stand alongside a conveyor belt and manually go through the materials collected from homes and businesses in the area. Among the milk jugs, soda cans and empty cardboard boxes, they pick out foil tops from yogurt containers, broken charging cords and empty tubes of toothpaste. These items are considered “contaminators,” and they get sent straight to the landfill or incinerator.

Cathy Plume, vice chair of the D.C. chapter of the Sierra Club, calls this “wish recycling,” and said it’s a big problem in the industry.

“[People say], ‘This should be recyclable; I’m going to put it in the bin.’ Well, that doesn’t help anybody,” Plume said.

Sending non-recyclable items to sorting centers (plus items that are recyclable, but are not accepted in curbside bin programs), costs taxpayers or businesses more for unnecessary processing, Seldman explained. And if these items make it past manual sorters on the line, they can contaminate the final baled products.

Adam Ortiz, director of Montgomery County’s Department of Environmental Protection, sees the same better-safe-than-sorry approach to recycling in his county, which runs a dual-stream recycling program that collects paper goods separate from other materials.

“One thing that breaks our hearts is that so many people put so much material into the recycling bin that isn’t recyclable, and then it goes to the recycling plant and then we just end up sending it to the incinerator,” Ortiz said.

His advice to residents?

“If you’re not sure, look it up. And you may be surprised — there’s a lot of stuff that may be put in the trash that is recyclable,” he said. (Montgomery County’s website has an “A to Z” list of how to recycle and dispose of materials, from car seats to Christmas lights.)

Plastic bags are a major problem for single-stream sorting centers, since they often cause the facility’s machinery to stall or break down — sometimes multiple times a day — as workers have to stop and cut the bags free. Leaders in the area are telling residents to keep plastic bags away from the recycle bin and to never bag their recyclables in a plastic bag. Instead, plastic bags should be recycled at grocery stores.

“Anything in a plastic bag, they don’t even open,” Plume said, referencing the recycling sorting center employees. “They are working so fast, they don’t take time to open it, so that’s just going to the landfill.”

Glass is another item that often gets sent from the sorting center to the landfill, and this is a problem local leaders are working to resolve. (Montgomery County is an exception; its dual-stream system allows for glass recycling, although Ortiz said the county is looking into facility upgrades to make it more efficient.)

The issue is that glass comes in many colors and often breaks, making it too difficult to separate from other materials. Plus, there isn’t as big of a market for recycled glass, compared to other products, such as cardboard and plastics.

“The fact is that when you do put the glass in our single-stream system, it costs a lot and it doesn’t do much good,” said Seldman, of the Institute for Local Self-Reliance.

Arlington County, Virginia, recently asked its residents to stop putting glass in its curbside collection program. Solid Waste Bureau Chief Erik Grabowsky explained it was costing the county a lot of money to have glass hauled to the recycling centers, only to then be taken to the landfill. (Many municipalities are charged by weight to process recycling and dispose of trash, and glass is one of the heavier items. Arlington County reports it saves $28.84 for each ton of glass diverted from the recycling stream to the waste stream. Arlington pays $72 to process a ton of recyclables.)

Until the region sets up a better infrastructure to handle glass recycling, Grabowsky said residents can save their glass bottles and containers and take them to one of two drop-off locations in Arlington. The glass collected at these sites will get processed and crushed at a facility in Fairfax, Virginia, and be used in construction and road projects.

The cleaner, the better

Making sure materials are clean is an important step to ensure that what gets put in the recycling bin actually gets recycled. Washed peanut butter jars, rinsed laundry detergent bottles and pizza boxes free of grease make the final baled materials more valuable. If sorters find items are too dirty to mix with the other products, they’ll send them to the trash.

“I think fundamentally, people need to realize that recycling is about commodities,” Grabowsky said.

In fact, it’s a $200 billion global industry.

“Gum that clean waste stream up with a bunch of peanut butter or jelly or oil that was just left over, then you’re taking a very valuable product and degrading it,” Plume added.

The U.S. recently had a recycling contamination “wake-up call,” Ortiz said, when China, which was the leading importer for the world’s recycling, announced it would no longer accept recyclable materials containing more than 0.5% impurities — a near-impossible standard under the United States’ current recycling system.

“For a long time, many years, China was willing to take all of the world’s plastic. … Ships were coming over to the U.S. with Chinese goods; ships were going back to China with a bunch of our plastic. That’s not happening anymore,” said Plume, who explained that because the contamination levels were so high among the materials the U.S. sent to China, a lot of it just ended up in China’s trash stream.

What the ban has done, Grabowsky added, is “really change the dynamics as far as the contamination levels.” Lower-grade materials are harder to market, and most U.S. recycling programs don’t have the systems in place to meet China’s new contamination standards. Some U.S. cities and towns have even stopped their recycling programs because of the ban, The New York Times reported.

And the impact has been felt close to home. Montgomery County’s Ortiz said prices have gone down for baled recycled materials. (Revenue generated from the sales of recyclables helps to offset the costs of providing overall solid waste services in many municipalities.)

“But in my opinion, it’s just a market correction like any other,” Ortiz said. “So we’re taking a little bit of a financial hit, but most of us jurisdictions are hanging in there.”

The new ban does present some opportunity, however: Since China stopped accepting paper from the U.S. — a relationship Ortiz called “awkward … because we’re environmentalists recycling, but we’re sending our Washington Post halfway around the world to be recycled [which] is a little bit hypocritical” — the U.S. has seen an uptick in the domestic pulp (paper) manufacturing market.

“Seventeen pulp plants in the United States are growing, two more are online to be built, and they’re taking the paper that China used to take a couple years ago,” Ortiz said. “So this is great for U.S. jobs.”

Montgomery County is working to reduce its trash and get its waste diversion up to 70% by 2020 from its current rate of about 62%, and Arlington County is working to reach a 90% diversion rate from the current 49% by 2038. Among other programs and policies, Ortiz said, more efficient sorting technologies and an upgraded recycling infrastructure are crucial to achieving these goals.

“We’re expecting — and not just Montgomery County, but in the region — we’re expecting 2020 or 2030 results on a 1990s recycling model,” Ortiz said.

“So we all have to up our game a little.”

What is recyclable?

What’s accepted in curbside recycling programs varies, depending on where you live. And many counties offer drop-off locations for electronic waste, hazardous waste (paint and other chemicals) and hard-to-recycle household items. Check out the links below for your area:

- D.C.’s Zero Waste website offers a “What Goes Where” tool for residents.

- Montgomery County’s Department of Environmental Protection has a similar tool, plus an “A to Z” directory on how to dispose of everyday items.

- Fairfax County helps its residents distinguish what’s trash and what’s recycling.

- Arlington County’s “Where Does It Go?” helps with disposal decisions.

- Prince George’s County also has a list of acceptable items on its website.

- Prince William County’s A to Z disposal guide can be found here.

- City of Falls Church, Virginia has information here.

- Information on recycling in Alexandria, Virginia is here.