WASHINGTON — Nader Briman, 42, used to own a lingerie factory in his hometown of Homs, Syria, until it was destroyed by a rocket during the war. As violence ensued in 2012, Nader and his wife Rasha, 36, decided it was best to flee the country with their three children.

The Brimans moved to Egypt, where Nader found work making wedding dresses at a bridal shop until he and his family received approval from the UN to come to the U.S. as refugees. They arrived the night before President Donald Trump’s inauguration at Reagan National Airport and were taken to their new home in Landover, Maryland.

Since their arrival, Briman has applied to several jobs, including Costco and Wegmans, but hasn’t found any luck. As a result, he is creating his own opportunities by applying his skills as a tailor from home. Nader is like many resettled Syrian refugees who are using their skills to try and make a living for themselves and their families.

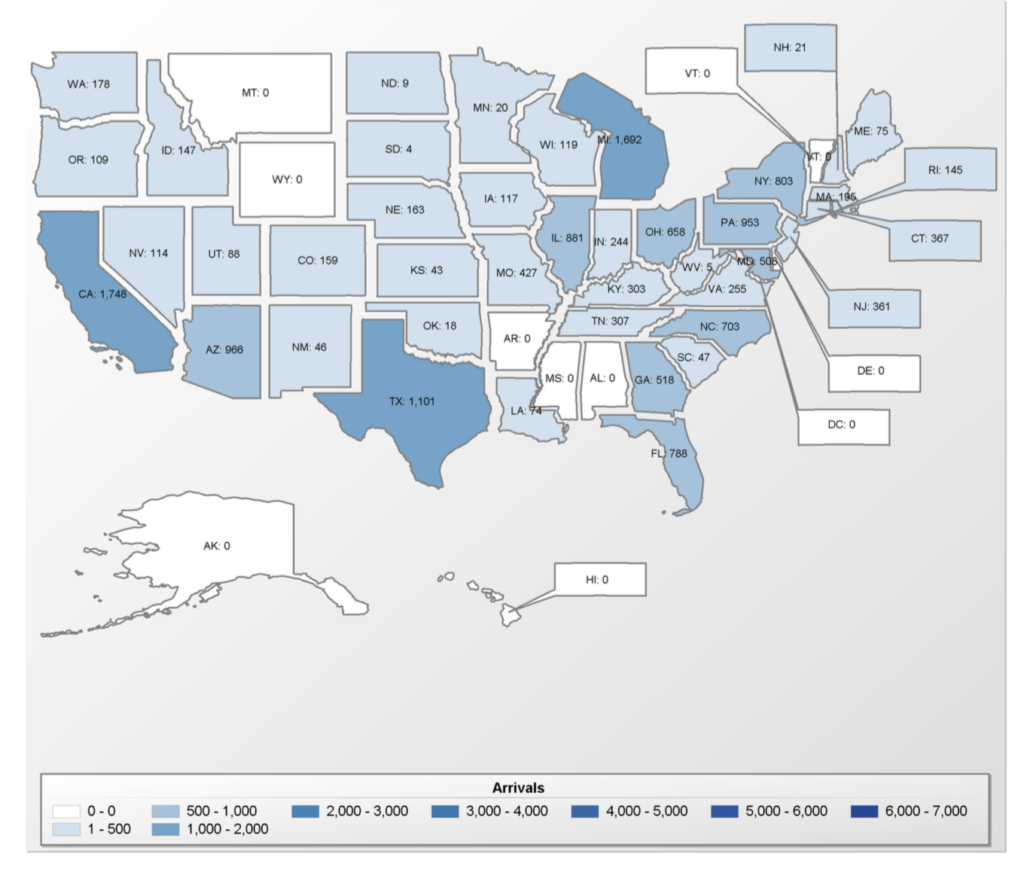

According to the State Department’s Refugee Processing Center, 15,479 Syrian refugees arrived to the United States in 2016.

Currently, there are 185 Syrian refugee families resettled in Maryland and Virginia, according to Raghad Bushnaq, the executive manager and founder of Mozaic, a nonprofit that aims to help refugees and people in need in the D.C. area.

Some families are resettled in areas as far as Charlottesville, Virginia, and Dundalk, Maryland, Bushnaq said.

Bushnaq, who is also from Syria, started Mozaic last April when she noticed there was a high number of refugees resettling in the area. Part of the work she has done is furnish their homes before they arrive, provide them with English classes and help them find suitable jobs.

Syrian refugees arrive to the U.S. (2016)

Finding Work

Even though refugees are granted work authorization as soon as they arrive in the U.S., Bushnaq said it’s been difficult for many of them to find and keep jobs.

Some of the agencies that work with refugees locally, such as the International Rescue Committee in Silver Spring, Maryland, and the Ethiopian Community Development Council, offer jobs to refugees that are sometimes not feasible, Bushnaq said.

For example, some of the refugees work in refrigerators where they are expected to cut meat and unpack vegetables.

“The environment is very difficult, so only few survive in this job,” Bushnaq said. “Healthwise, they couldn’t stand it.”

Another issue, Bushnaq explained, is that most of the jobs are seasonal and only last up to a month or two.

While Bushnaq said that some of the refugees enjoyed working in bakeries, the early hours were problematic since they would have to wake up at 2 a.m. and ride the bus, which would sometimes take them two hours to get to their job.

Language also poses a barrier in the job search. Although Nader, along with other refugees, takes classes at Montgomery College three times a week to learn English, it’s still a challenge.

“I’m trying my best to perfect the language so I can enter the workforce here,” Nader said, in Arabic. “Once we learn the language, it will be much easier.”

Although Nader hasn’t found a job yet, he strives to be self-sufficient. He said he’s not waiting on organizations to provide financial help. He wants to stand on his own two feet.

“They are offering us help, but I want to work,” he said.

Story continues below gallery.

On Their Own

Nader’s willingness to work and be self-sufficient has pushed him to create his own work opportunities, and he’s not the only one.

After working closely with refugees within the past year, Bushnaq realized many of them are experts in building, cooking and sewing. As such, Mozaic is helping them utilize the skills they already have to create their own businesses.

Bushnaq said the organization provides them with tools and supplies donated by people in the community so they are able to start working.

Nader received an industrial sewing machine from Mozaic in April. He uses the machine to make dresses for his clients.

“I want to try my hardest to prove to myself and others that I am hardworking and ambitious,” Nader said.

Nader has received clients mainly through word-of-mouth. Bushnaq has also posted several pictures of wedding dresses Nader has made in the past on the Mozaic Facebook page.

Rasha, Nader’s wife, said she’s happy to see her husband behind a sewing machine again, since she knows it’s a passion of his.

Nader said he’s hopeful he can make sewing and designing dresses a business for himself in the D.C. area.

Another business many refugees are prospering at is catering.

Rasha started catering about two months ago. “My husband hasn’t found a job, so with the house, the kids and expenses, I said I’m going to try to get into it,” she said.

In March, Mozaic hosted a Flavors of Syria event at National City Church in D.C. to celebrate Syrian culture with food, singing and dancing. All the food at the event was prepared by Syrian refugees.

Rasha cooked 300 pieces of kebba mashwiye, a traditional Syrian food made of wheat, onions, beef and spices. According to Rasha, all 300 pieces she made were sold at the event, which has brought her some business.

“People started eating my food and those who like it, order it right away,” she said.

Rasha makes other Syrian foods such as bourek, shawarma, meat pies and chicken dishes.

“I make all of it,” she said with a smile.

Bushnaq, who sometimes serves as a middleman between customers and the refugees, said she was overwhelmed with orders from people after the Flavors of Syria event.

“Sometimes I receive orders at 1:30 a.m., and I have to process them and get the prices, and be the connection between the people who are having the party and the refugees,” Bushnaq said.

As such, Bushnaq and other volunteers are developing a website called Mozaic Kitchen, where people can see the different chefs, what they make, their prices and order from there.

Customers will also have a chance to order preserved foods such as homemade cheeses, lebne (yogurt) and maqdoos (stuffed eggplant). The refugee chefs also make Syrian desserts and pastries.

Bushnaq, who has established a personal relationship with most of the refugee families in the area, hopes to see them prosper with their businesses and integrate into society.

Story continues below timeline.

Community Support

Nader said the community has been a source of support for him and other refugees in the area.

“They helped us a lot and eased our situation,” he said.

The refugees have also banded together for support. Many of them live in the same neighborhoods, and their children often play together.

“We have all the refugees in one WhatsApp group with daily advice,” Bushnaq said. “Whenever they have an issue, of course, they call or send it on the group.”

Overall, Nader said the D.C. area has been welcoming to him and his family.

Audrey Singer, a senior fellow at the Urban Institute, researches refugee resettlement, immigration and demography in U.S. cities. She said that there is a tradition of refugee resettlement in the D.C. area, and that’s one of the reasons why the area is suitable for welcoming new refugees.

“Public reception of refugees is an important factor as well, and because Washington has people from all over the place, it does help,” Singer said.

Despite Trump’s stance on the refugee resettlement program, Singer said there’s still a tremendous amount of support for it.

“Most people recognize this is a program about humanitarian protection and support, and I think most people will get that,” Singer said.