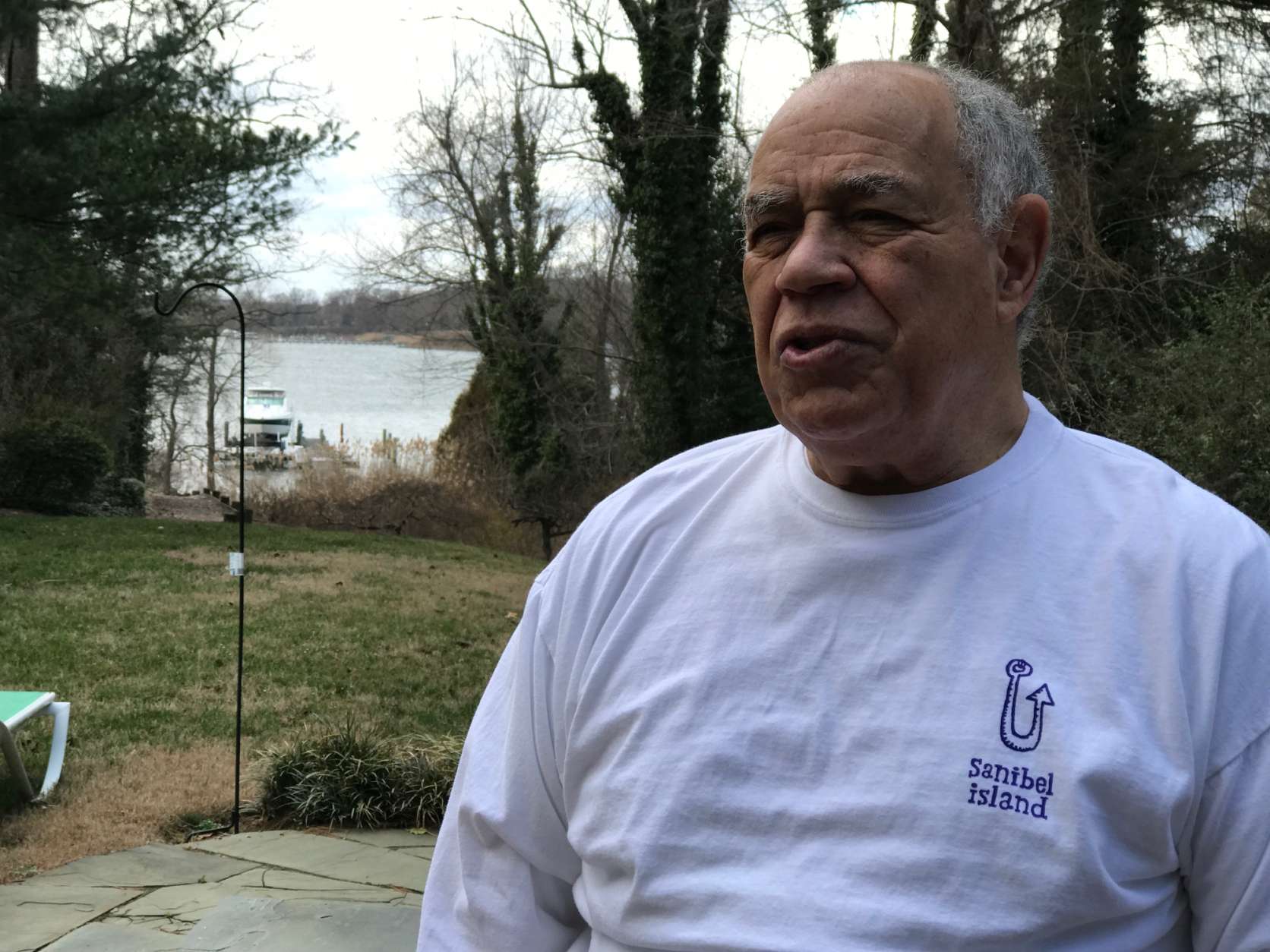

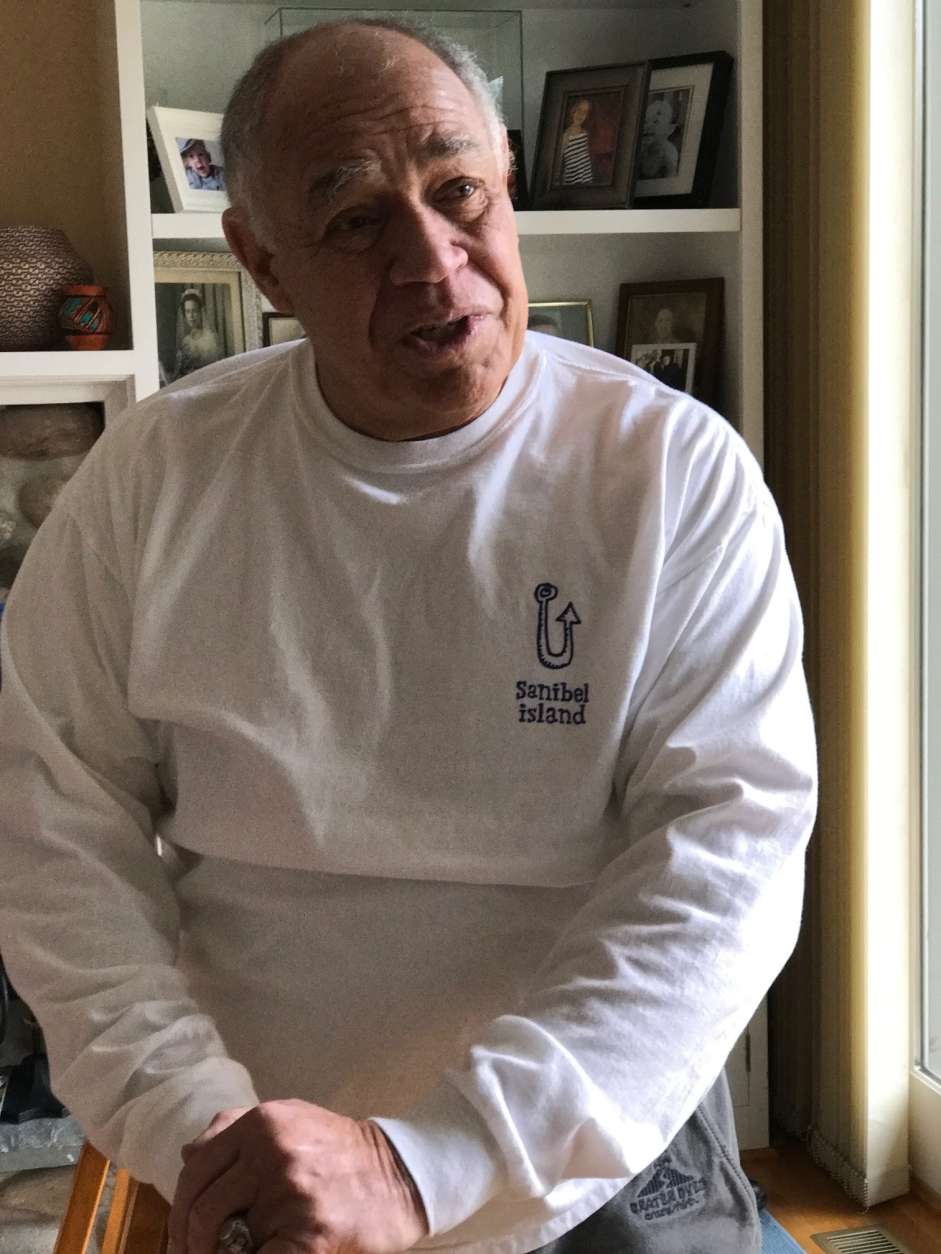

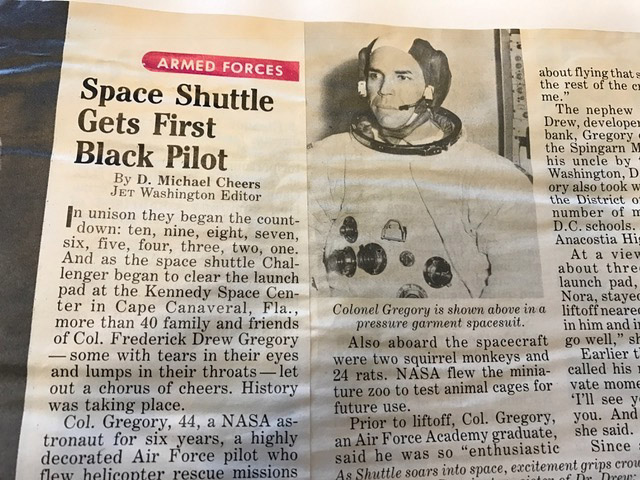

WASHINGTON — Black pioneers extend across professions and around the globe — and in Frederick Gregory’s case, beyond Earth’s atmosphere.

The D.C. native’s journey to the stars began in childhood, with experiences that served as a launch pad toward a historic achievement — becoming the first African-American to pilot a space shuttle mission.

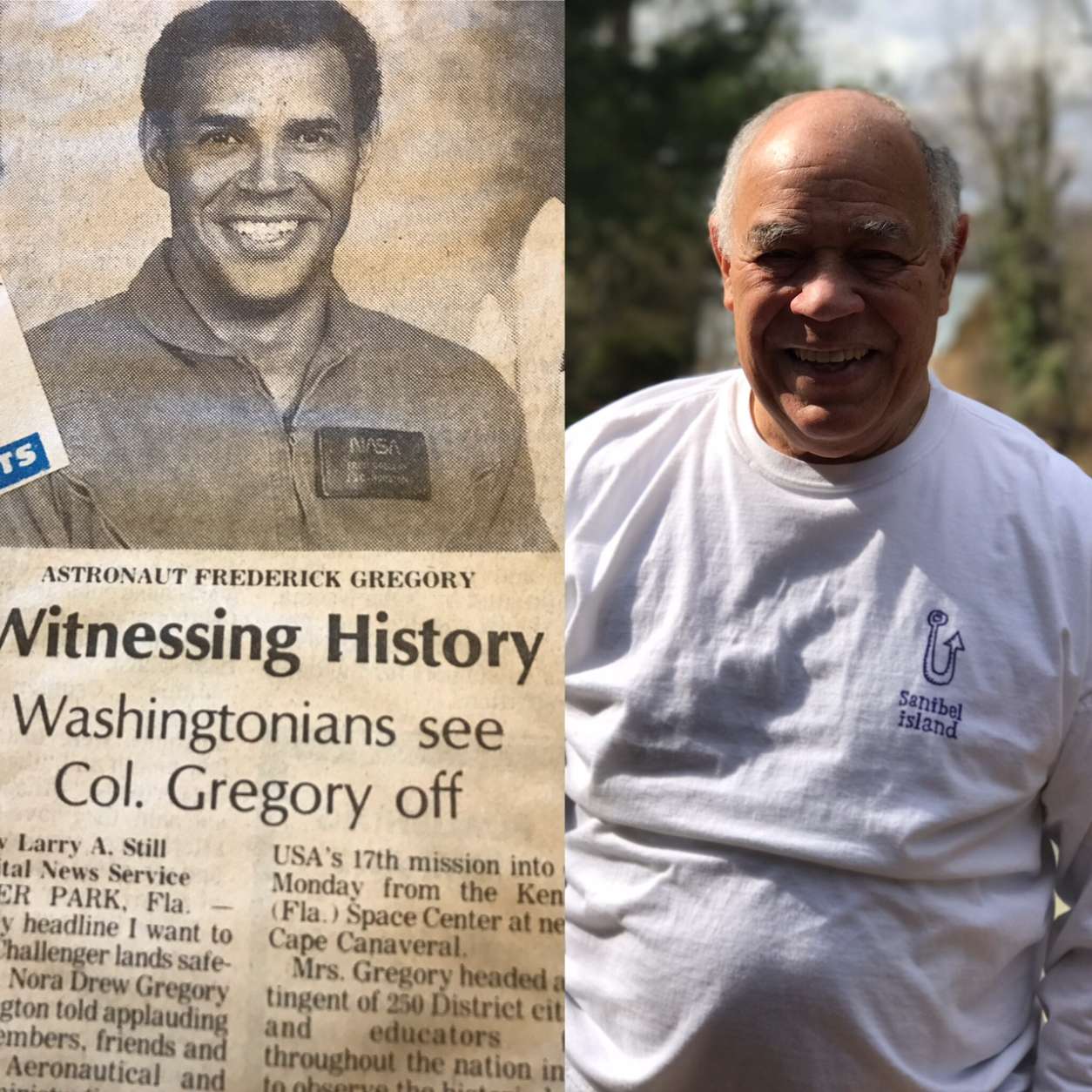

He realized what many others only dream of on April 29, 1985, aboard the space shuttle Challenger. Reflecting on that successful flight, he saw it as a way to contribute to something much bigger, and he credits his parents for inspiring him to strive toward that.

“My parents encouraged me to do something tomorrow I thought was impossible yesterday,” Gregory said. “So I was always looking for a challenge.”

The former astronaut’s family lineage served as an inspiration as well: His great-grandfather, James Montgomery Gregory, was one of Howard University’s first graduates in 1872; and his uncle, Dr. Charles Drew, helped organize America’s first blood bank.

It all motivated Gregory to pay it forward to the next generation.

Obstacles, but no ceiling

Growing up in segregated D.C. meant facing numerous social barriers. His parents insulated him as much as they could so he would see no ceiling.

Because the Boy Scouts of America forbid integration, for instance, his parents helped organize an African-American Cub Scout troop that met in Frederick Douglass’ home.

And Gregory’s father, Francis, would take him to see air shows at what was then Andrews Air Force Base. “I was introduced to airplanes there. You could just walk out on the ramp and talk to the pilots,” Gregory said.

As a youngster, Gregory sat in the front seat of an airplane piloted by Gen. Ben Davis of the Tuskegee Airmen. He had to sit on a few phone books to see out of the window.

It was a moment that cemented his fascination with planes.

Air Force, then NASA

Gregory excelled in grade school and graduated from the Air Force Academy in 1964.

After getting his flying credentials in 1965, Gregory served as a helicopter pilot during the Vietnam War. But he was not living up to his mantra — contribute and have fun.

“I was a helicopter pilot, then a fighter pilot, then a test pilot. … And honestly, in my middle 30s, I got bored doing that. And I just happened to see an advertisement that said, ‘Apply for the astronaut program. Be a space shuttle pilot,’” Gregory said.

While contemplating that next step, the former Tuskegee Airman offered his support.

“He said to me, ‘Gregory, I want you to join the Tuskegee Airmen, and I want you to apply for the astronaut program.’ That meant the year 1976 would be very exciting,” Gregory said.

At NASA, the grueling training that Gregory endured seemed more like fun than a test.

Experiments testing human adaptation in a zero-gravity environment went from being eerie to cool, he said. While he could perform everyday tasks like sleeping, he realized that he had to make adjustments to fit a setting where everything floated.

And NASA’s training team frequently put Gregory and his team in precarious scenarios.

“The training team was always trying to kill us, and we were always trying to make fools out of them,” Gregory said.

It was an environment “full of giggles and smiles,” he said, but coming to terms with the possibility of death on a mission was something that he had to overcome. “We had learned to accept death as a part of making advances.

“From our point of view, the saying ‘failure is not an option’ was not correct. Failure is an option. You had to accept the fact that you may not survive.

“And when you get to that point, then you were able to use your mind to think of alternative ways to survive through the scenarios,” he said.

Liftoff

When the time came to liftoff, Gregory said, he was all smiles not because he was getting ready to make history, but because he was getting the opportunity to contribute and have fun.

“I was traveling 17,500 miles per hour. It was fun,” he said. “We orbited earth within an hour and 30 minutes. At that speed, you can travel from New York City to London in five minutes.”

It was the first of three shuttle missions for Gregory: He flew aboard the space shuttle Discovery in a 1989 mission and aboard the space shuttle Atlantis in 1991, logging more than 455 hours in space total.

From space, Gregory said he had a mesmerizing and holistic view of earth. “I was seeing events from space, happenings from afar, the earth’s weather system.

“Since you can’t see borders and things like that, it would be great if our political folks would go up and see the world from that vantage point,” he said. “As opposed to the very localized area that they’re in. …

“You change, your whole philosophy changes, your whole outlook changes.”

Paying it forward

Back on Earth, the Annapolis resident continues to pay it forward by going into classrooms around the country, where he discusses space exploration, his own journey and how everyone should find a way to contribute and have fun.

And while Gregory holds a prominent, historic role in the mosaic of African-American history, he also sees himself as having a prominent role in one of mankind’s greatest achievements:

Traveling 17,500 miles per hour.