EDITOR’S NOTE: This is the second story in WTOP’s series “Hooked on Heroin: Deadlier than ever,” exploring the how the rise in prescription painkillers has contributed to the heroin epidemic.

WASHINGTON — A year ago, if you had your wisdom teeth removed, you might have been prescribed more than 20 hydrocodone pills. Or an emergency doctor might have given you a month’s worth of Percocet after a minor car accident.

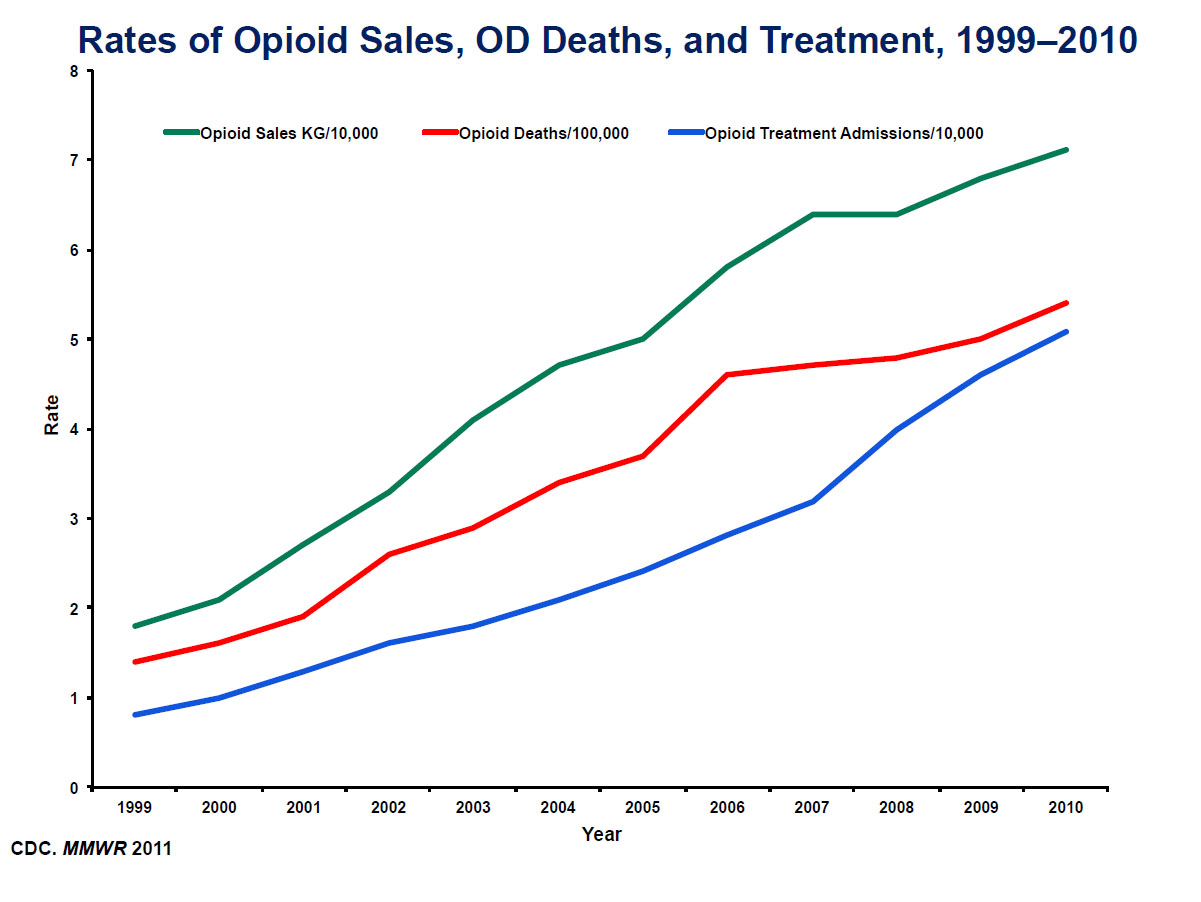

But the practice of aggressively treating pain is changing. Experts say the over-prescribing of opioids in the last 15 years has contributed to the nation’s current heroin epidemic — a slippery slope from recovering patient to recovering addict. Four out of five heroin addicts first became addicted to painkillers, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration says.

New CDC guidelines advise doctors to prescribe fewer painkillers for acute pain. And some physicians have even been arrested for selling massive quantities of opioids to drug users.

So is it the doctors’ fault?

Under the microscope

“There has been a marked increase in the prescribing of opioids,” said Dr. Nancy Nielsen, former president of the American Medical Association and currently senior associate dean for Health Policy at the Jacobs School of Medicine at the University of Buffalo.

Opioids have been used to treat acute or chronic pain for decades, but officials are starting to realize that patients, who have legitimate pain, are getting hooked.

In 2012, health care providers wrote 259 million prescriptions for opioid medications — enough for every adult in America to have a bottle, and a 7 percent increase over 2007.

Since 1999, sales of prescription opioids in the United States have quadrupled, according to the CDC, and nearly 2 million Americans were dependent on opioid medications in 2014.

The reason prescriptions have skyrocketed, Nielsen said, is twofold.

First, “We were told by the pharmaceutical companies that these newer drugs were not addictive and that they were safe. None of that was exactly true,” Nielsen said.

Second, patient satisfaction surveys would essentially grade doctors on whether they “totally” treated patients’ pain.

The questionnaires were used by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to determine how much money the hospital would be reimbursed. The system incentivized employers to make decisions about patient care that might not have been in patients’ best interest.

“It wasn’t direct financial incentive or disincentive to the doctor, but it was to the hospital.”

So doctors were caught in the middle.

“Doctors have always tried to deal with their patients’ pain,” Nielsen said. But if a doctor refused a drug-seeking patient, there would be serious consequences if the patient handled the survey in a retaliatory way. The hospitals, in turn, came down on the doctors who appeared to not be adequately treating patients’ pain.

“All of that contributed to having doctors become … probably way too cavalier and too ready to use these drugs,” Nielsen said.

After nationwide backlash from medical professions, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services changed the way the questions would be analyzed and used in November. While the pain management questions remain, the new rule de-links patient responses from any financial incentives to a hospital or practice.

But under a new federal law that went into effect this month, doctors who treat Medicare patients will eventually receive incentives or penalties tied to satisfaction surveys.

The Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act replaces the traditional fee-for-service system with a value-based structure. Advocates hope the system will help improve bedside manner and overall care, but critics say it will bring complications and potential conflicts of interest because treating pain with opioids could cause more harm than good, in some cases.

It’s a particular concern for oral surgeons who regularly prescribe painkillers for tooth extractions. A 2016 study by the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine and School of Dental Medicine found that half of the opioids prescribed for dental surgery went unused.

Patients were prescribed an average of 28 pills; after three weeks, 54 percent were left over.

“When translated to the broad U.S. population, our findings suggest that more than 100 million opioid pills prescribed to patients following surgical removal of impacted wisdom teeth are not used, leaving the door open for possible abuse or misuse by patients, or their friends or family,” said lead author Brandon Maughan, an emergency physician.

“Results of our study show within five days of surgery, most patients are experiencing relatively little pain, and yet, most still had well over half of their opioid prescription left,” said co-author Elliot Hersh, a professor at Penn Dental Medicine.

Instead, Hersh said, over-the-counter drugs, such as ibuprofen and Tylenol, should be used to ease oral surgery pain.

In fact, Nielsen said, most dentists will advise that opioids are not necessary for tooth extractions, and if a prescription is needed, patients should ask why it’s being given and for how long.

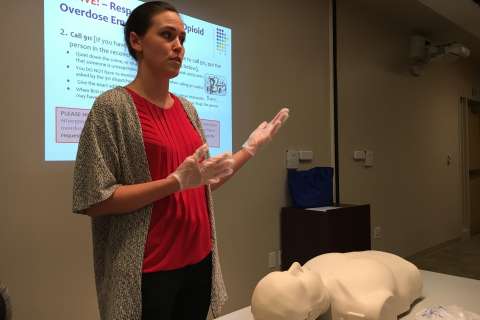

And it’s not just dentists under the microscope. In March 2016, the CDC issued new guidelines to primary care physicians to avoid prescribing opioids as a first line of defense against pain. Drugs such as OxyContin and Vicodin should be limited and only given at the lowest doses because of the risk of abuse. The CDC is urging doctors to only write three-day prescriptions, as opposed to 30- or 60-day prescriptions, for short-term pain. In cases of chronic pain, follow-ups should be scheduled more frequently.

In a landmark report, the U.S. Surgeon General in November called for a cultural shift in the way Americans viewed addiction. Dr. Vivek Murthy said 78 people die each day from an opioid overdose, and he said he hopes the findings shift public opinion like the Surgeon General’s report on smoking 50 years ago.

But the public’s opinion about the painkiller problem is split. A poll by Stat-Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health found that 37 percent of Americans blame drug users while 34 percent say doctors are responsible for writing too many prescriptions.

“We are all part of the problem, and doctors have a role to play here, because we’re the ones who prescribe it,” Nielsen said.

Pain management and the octopus from hell

Americans, Nielsen said, don’t like to be in pain. “We don’t like discomfort of any sort. We don’t tolerate it well.”

As new scientific research and technology were developed, new drugs were marketed to the public for all kinds of pain applications. The popularity of these drugs grew, and to meet the demand, pharmaceutical companies developed long-lasting doses to more effectively eradicate pain, such as OxyContin, an extended-release version of Oxycodone.

“You get an injury. You go see a doctor. He prescribes you pain medication and gives you a three-month supply. You take Dilaudid, Percodan, Percocet, Demerol, the list goes on, OxyContin,” said Second Lt. James Cox III, a supervisor for the Fairfax County Organized Crime and Narcotics Division.

But in recent years, pharmaceutical companies have been sued for misleading the public about how safe their drugs really are. In 2008, Cephalon paid $425 million to settle a lawsuit over the marketing of potent opioids for unapproved off-label uses, such as migraines.

Despite some pharmaceutical companies’ claims, research showed the drugs were incredibly addictive.

“The brain becomes very dependent on them,” said Nielsen.

Opioids, like heroin, are central nervous depressants that dull the senses and make the brain feel good, even happy. But they also have unwanted side effects — drowsiness, concentration issues, shallow breathing and apathy. A person who overdoses may slip into unconsciousness and never wake up.

Once someone is hooked, it’s nearly impossible to stop.

Anne Arundel County Police Chief Tim Altomare calls it “an octopus from hell” that infiltrates every aspect of someone’s life. “It’s poison. Everyone knows it’s poison,” he said.

Even if the narcotic is used as prescribed and for legitimate pain, the body builds up a tolerance and the brain starts to crave it. When the opioid-dependent patient returns to the doctor but is denied another prescription, they may seek another, cheaper option.

“Why pay $40 for an OxyContin pill when I can buy a $10 bag of heroin?” Cox asked.

Once hooked, repeat users need a baseline opioid fix to live day by day.

“They’re waking up in the morning and if they don’t have that drug, they’re going to be vomiting, sweating profusely. As soon as they’re up, they’re going to buy their heroin just so they can make it through the day,” said Cox. “Nobody wakes up and says they’re going to be a heroin addict today.”

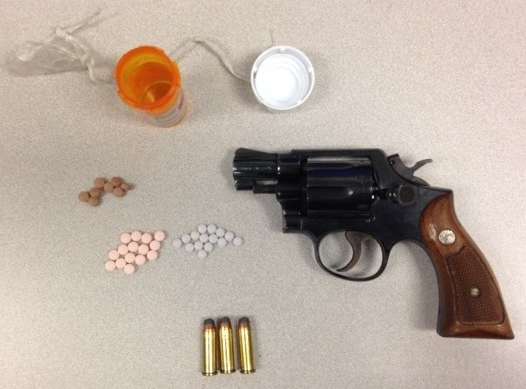

Pill mills

But law enforcement officials say some doctors are actively contributing to the rising opioid addiction rate.

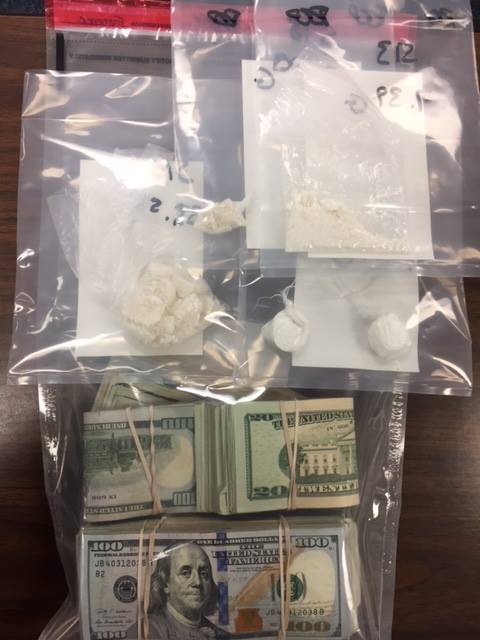

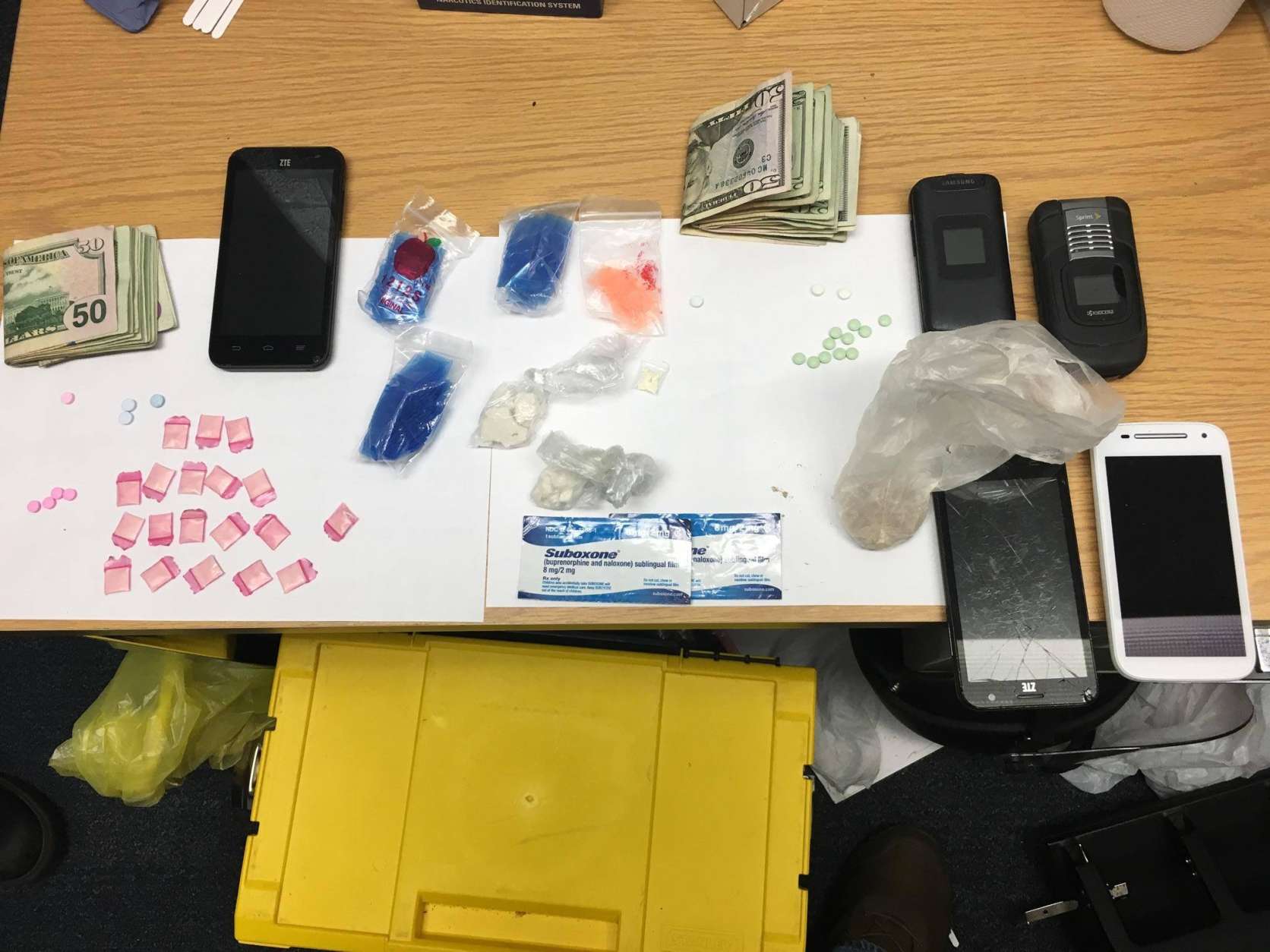

Police departments have cracked down on “pill mills” — practices or clinics that knowingly prescribe narcotics to patients who are addicted to them. In August 2016, Prince William County psychiatrist Craig Charles Krause was arrested for selling thousands of Xanax pills, a popular sedative, to drug dealers.

Under Maryland’s Prescription Drug Monitoring Program, created in 2014, doctors and pharmacies are required to report each prescription to the state, allowing the government to identify and investigate physicians who are taking advantage of the system. Virginia and D.C. have similar databases.

“These drugs are life-saving drugs; they are also life-altering and life-ending drugs if used inappropriately,” Nielsen said.

Read more on Wednesday as the series continues: A parent who said he was in denial about his child’s addiction and why kids are the most at risk.