EDITOR’S NOTE: This is the first story in WTOP’s series “Hooked on Heroin: Deadlier than ever,” exploring the deadly synthetic opioids that are fueling the region’s heroin epidemic.

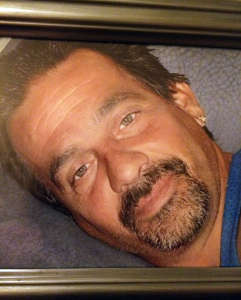

WASHINGTON — After two years behind bars, 46-year-old Worth “Danny” Lancaster walked out of the Fairfax County jail on Feb. 10, 2015. The next day, he was dead.

“(Heroin) is the most powerful drug there is on Earth. It’s a wonder I’m still alive,” Lancaster told WTOP in 2014, just weeks before his release.

Lancaster was one of thousands of D.C.-area residents who have died of a heroin or opioid overdose in recent years. Opioids are the No. 1 cause of injury-related deaths in the nation, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says.

The crisis has reached a boiling point in the region, as a new breed of designer opioids has infiltrated the region’s drug market.

As the deaths continue to be tallied, at least 1,600 people in D.C., Maryland and Virginia died from heroin or opioid overdoses in 2016, and that’s just a preliminary figure. Several months of data from last year have yet to be published.

An epidemic

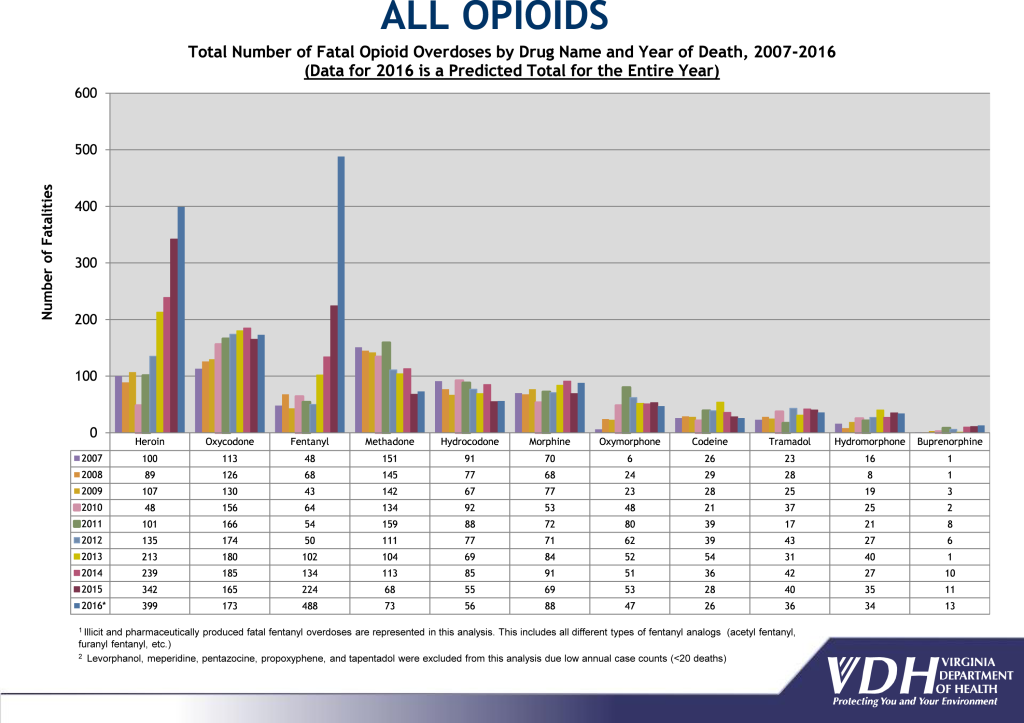

In November 2016, Virginia’s Health Commissioner declared a public health emergency. Officials projected that by the end of last year, a record of more than 1,000 Virginians would have died, an increase of 77 percent compared to five years ago.

Fairfax County has the second-highest rate of fatal opioid overdoses in the state after Richmond.

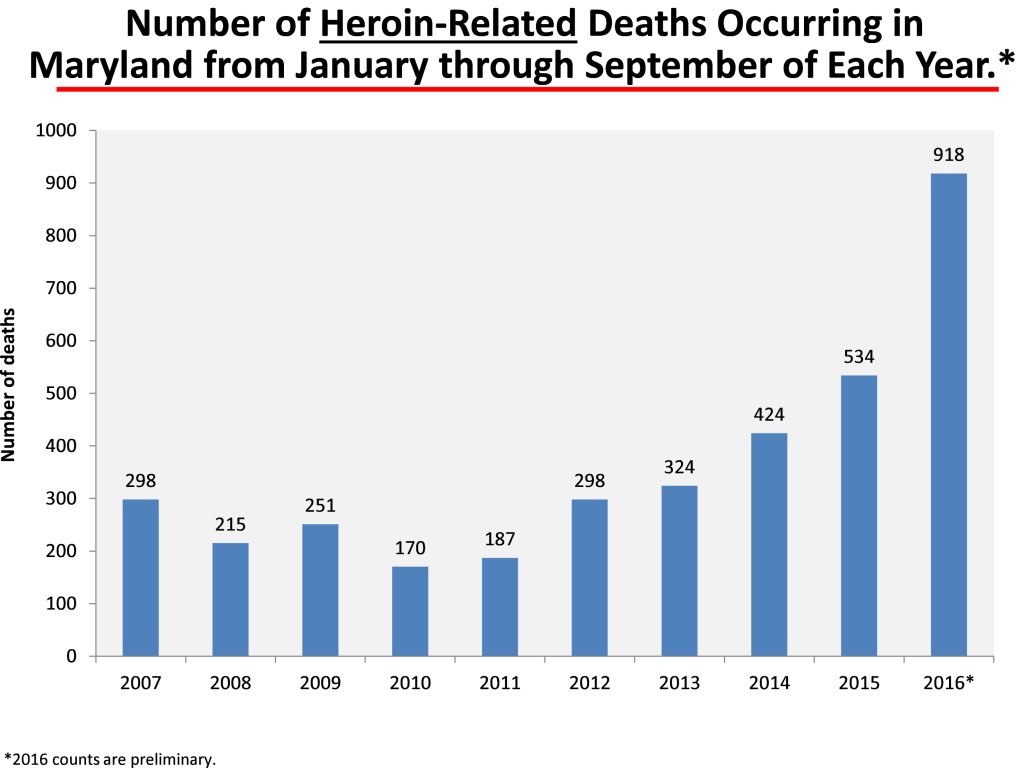

Meanwhile, in Maryland, heroin-related deaths jumped a whopping 70 percent in the first nine months of 2016 compared with the same period in 2015, according to the most recent data available from the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene.

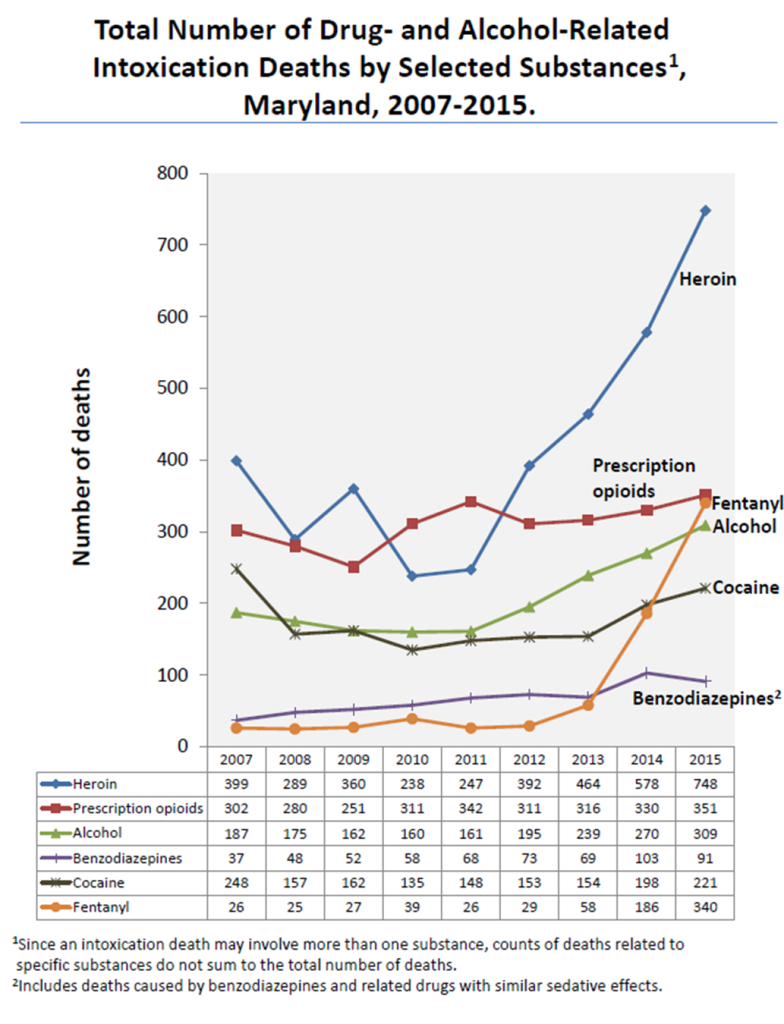

Heroin outpaces all other intoxication deaths, including those attributed to alcohol, prescription opioids and cocaine.

The Baltimore area is still the heroin capital of Maryland, with nearly 500 heroin-related deaths from January to September 2016 in the city of Baltimore and Baltimore County.

Nearby Anne Arundel County, where officials have declared a public health emergency, has the next-greatest rate of fatal overdoses; Prince George’s and Montgomery counties round out the top five. Every single Maryland county, except for Garrett, Somerset and Washington, has seen an increase in heroin-related deaths since 2015.

The District also is experiencing the same trend: The number of fatal heroin overdoses has increased every year the past three years. The Office of the Chief Medical Examiner reports that in the first half of 2016, 233 people died of an opioid-related overdose. Such deaths are most prevalent in Ward 8.

As potency skyrockets, so do deaths

Lancaster, a longtime heroin user, was in recovery during his incarceration, but just hours after he was released, his body was found lifeless in a car. The Virginia Medical Examiner’s report says he fatally overdosed from a combination of heroin, cocaine and alcohol.

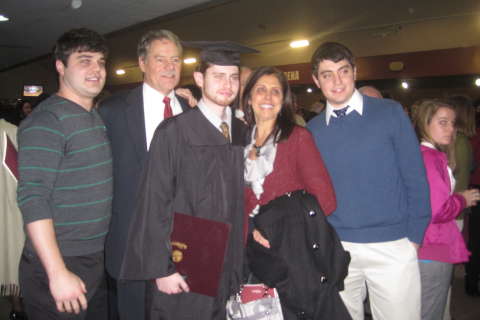

“He said he was so glad he was free and clean. He just wanted to start all over,” Lancaster’s mother, Lois Coffman, said.

“I knew that Danny had been addicted for so many years. But when he was clean, I just couldn’t believe that he would just go right back to it … I just cried. It just broke my heart.”

Lancaster had been in and out of prison for seven of the past 14 years, chasing the high. But even as a regular user, he was no match for the drugs. The year he died, drugs including opioids and heroin killed 50,000 Americans — a record. That’s more than vehicle crashes and gun homicides.

“I don’t think we’ve ever seen anything like this. Certainly not in modern times,” Robert Anderson, who oversees death statistics at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, told The Associated Press.

Heroin deaths jumped 23 percent and synthetic opioids, such as fentanyl, surged by 73 percent.

Though it’s unknown whether Lancaster’s heroin was laced with any synthetic additives, designer drugs manufactured overseas turn ordinary heroin into a lethal weapon so dangerous that even just touching them could stop a heart.

In the past two years, heroin’s potency has skyrocketed as drug dealers began regularly mixing heroin with synthetics, increasing the potency of the drug to 90 percent or more — levels law enforcement officials have never seen before.

“We’ve got a major problem. The first time a person uses one of those products with such a high potency level, it can stop their heart,” said Anne Arundel County Police Chief Tim Altomare, a 24-year veteran police officer.

In comparison, street-level heroin during the 1970s was about 3 to 7 percent pure, enough to make someone high but typically not strong enough to cause a regular user to fatally overdose.

“That wasn’t killing people then,” said Altomare.

Fentanyl: Fatal on contact

Fentanyl is a prescription drug legally produced to treat chronic pain for terminal cancer patients in the United States. It’s about 50 to 100 times more potent than morphine.

More people are dying from a heroin-fentanyl mix than any other lethal combination.

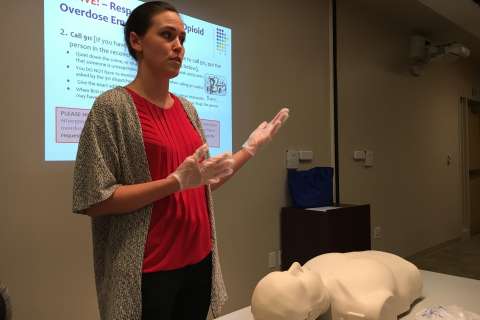

Fentanyl is so dangerous that police officers must wear protective gloves when responding to the scene of an overdose.

“We put safety equipment on because contact with the skin can stop the heart. We wear respirators so we don’t breathe dust in and we cover our skin with protective gear,” Altomare said.

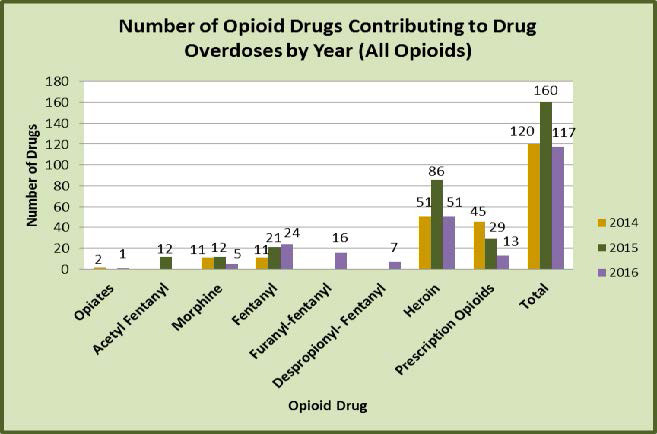

Second Lt. James Cox III, a supervisor for the Fairfax County Organized Crime and Narcotics Division, said fentanyl-laced heroin is on the rise in the D.C. area.

“We’re seeing this mass increase in overdoses,” Cox said.

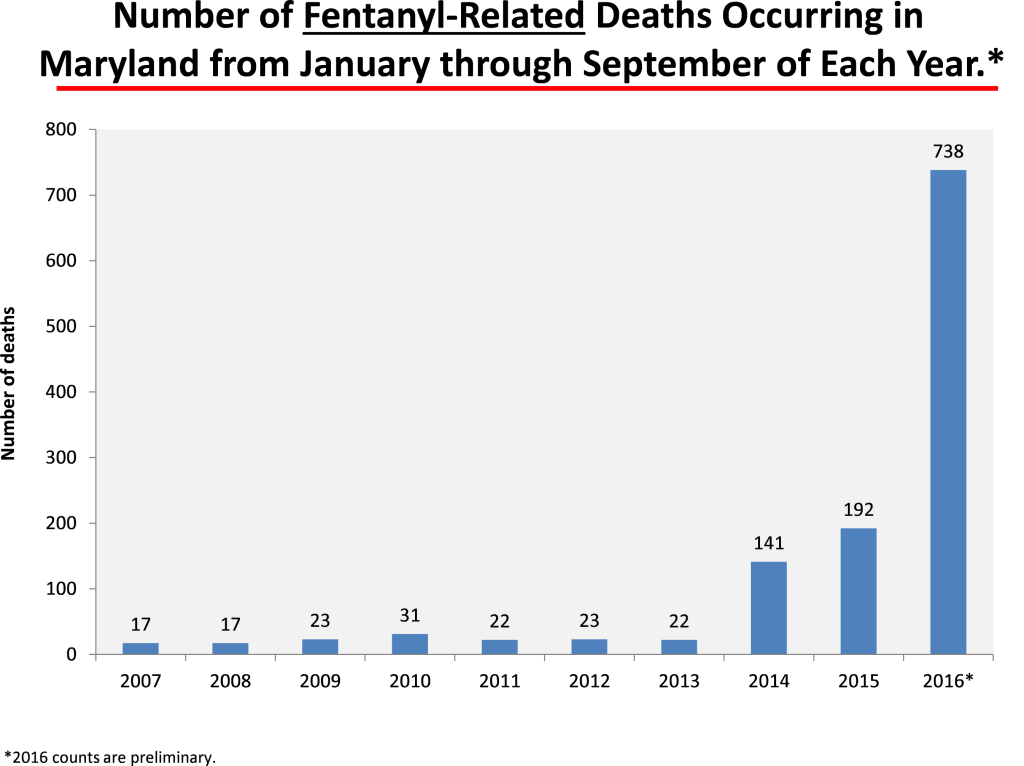

The number of fentanyl-related deaths in Maryland rose more than 280 percent in 2016, compared with the same period one year earlier. Officials cite the mix as the cause of more than 700 deaths from January to September.

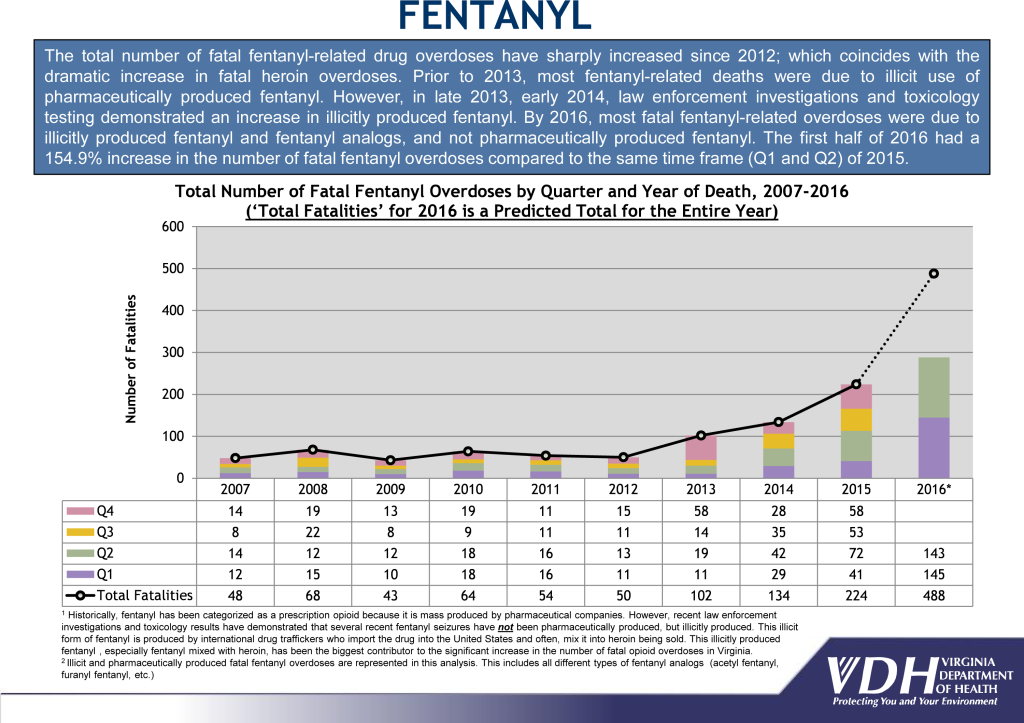

In Virginia, where the 2016 data is still being gathered by the Department of Health, the number of fatal fentanyl overdoses was expected to double from 2015 — from 224 deaths to nearly 500.

But fentanyl is not even the most deadly heroin additive. Recently, heroin laced with carfentanil — an elephant tranquilizer — was found in Fairfax County, Virginia Health Commissioner Marissa Levine said. Carfentanil is 100 times more potent than fentanyl, 10,000 times more potent than morphine.

Cooking up death

Criminals working in overseas labs use advanced technology to copy deadly compounds and add them to heroin. And these chemical concoctions are flooding into the local heroin market.

“It’s taking morphine and changing the chemical structure to make a synthetic look-alike to that drug,” Cox said. “If you have a really good chemist, they’re going to be able to synthesize heroin or fentanyl themselves.”

Law enforcement officials also have discovered heroin laced with designer drugs that hasn’t been seen in the United States before — a problem because, without an official name, these compounds can’t be classified as an illegal substance.

In November, the Drug Enforcement Administration added an illicitly manufactured opioid known as “pink” heroin — under the chemical name U-47700 — to the list of narcotics that have no medical use and are therefore illegal in the United States.

This synthetic drug is blamed for deaths across the country, but it hadn’t been regulated until now. Rogue scientists are developing new chemical compounds faster than the federal government can keep up.

The DEA’s action was too late to help a Loudoun County resident. An Ashburn man died after ingesting U-47700 back in July.

“When heroin comes into the United States, there is no such thing as a pure drug,” Cox said. “Dealers need to make money.”

So the dealers cut the product with additives to increase their profits and supply.

At your fingertips

Synthetic opioids can be ordered online from China, and the packages are shipped all over the United States. Meanwhile, the DEA said, poppy cultivation in Mexico remains the greatest source of high-purity, low-cost heroin in the United States, especially in the Northeast. Dealers combine synthetics with heroin to create a super drug.

Cox said police investigated two cases in Fairfax where several residents ordered synthetic fentanyl mailed directly to their home. In one instance, a Reston resident injected fentanyl-laced heroin and immediately overdosed. His body appeared lifeless but because of a quick-thinking roommate, first responders arrived on the scene to revive the man with an antidote called naloxone.

“When placing an order on the internet, especially if it’s from some underground lab, you have no idea what you’re getting,” said Cox. “Somebody could make it in their basement as long as they have the chemicals to do it and the know-how.”

Altomare said synthetics allow dealers to stretch the product out and it gives them “more bang for the buck.” Unlike traditional cutting agents, which dilute the heroin, these additives increase its potency.

“People who are in the cycle of addiction are looking for the strong products,” Altomare said.

Danny Lancaster started snorting heroin in his early 30s with his fiancee until she overdosed and died in 2000. His life spiraled out of control and he fell into a deep depression. He stole to fund his addiction, shooting $150 to $300 worth of heroin a day.

After three years in recovery behind bars, it only took a few hours of freedom for Danny Lancaster to slip back into old habits.

The morning of his release, Lancaster took the bus to the Krispy Kreme along U.S. 1 to meet his brother, Tim. The two brothers had coffee and doughnuts and talked about Lancaster’s new life. They planned to meet up again around 4 p.m. to have dinner.

But that never happened.

Tim’s calls went unanswered. His brother never answered the phone. Early the next morning, police found Lancaster’s lifeless body in a car nearby.

“That disease made me do something I didn’t want to do every day,” he told WTOP while he was still behind bars, just weeks before his fatal overdose. His dream was to mentor young adults who were struggling with drugs too.

“I want to talk to young people about addiction. It’s going to be hard with my record. But I can share stories. I just want to change.”