It is both a hobby and a history — sea glass hunting around the Chesapeake Bay.

Fall begins Wednesday, but don’t let it keep you away from the beach. Cooler temperatures make autumn a perfect time to search for sea glass.

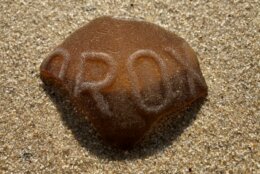

It’s glass that was once trash, transformed into frosty drops of treasure by decades of exposure to water and waves. All you have to do is pick it up.

Beaches around the Chesapeake Bay are a great place to start your search. Nancy LaMotte of West Fenwick, Delaware spoke with WTOP about her search for sunken shards. She’s an artist and metalsmith who designs sea glass jewelry and sells it online and at festivals.

“I originally started looking for sea glass when my two children were very little … to get them outside and in the fresh air and do something fun,” LaMotte told WTOP. “I think I was surprised at what I was finding on the Chesapeake Bay.”

She said that she was surprised by and attracted to the appearance of the glass, drawn to hunt glass by the history it revealed.

“I was surprised that the pieces were so well worn and so beautiful and so gem-like in quality,” said LaMotte.”

History revealed

About 85% of sea glass comes from old bottles, according to LaMotte, and the most commonly found colors of sea glass are brown, green and white. Not a lot of bottles were made in colors like red, orange and yellow.

“They actually used a small percentage of gold in the batch of glass itself to maintain that color, and it was very, very expensive,” LaMotte said. “The pieces that are rarer are the 15% that’s coming from tableware or boat signals … old ship lanterns, things like that…”

She especially enjoys finding old or unusual shards that are not conventionally attractive. For example, clear glass that was made before 1915 with manganese dioxide can turn purple once it’s exposed to light for a long time.

When it comes to figuring out where a particular piece of sea glass came from, LaMotte suggests digging online, checking out books from the library about vintage bottles, or visiting bottle shows.

“Just going into a bottle show has helped me attach a piece of sea glass to an actual vessel that is sitting on the table from 1930 that was a master ink bottle that I’ve never seen in my life,” she said.

Most sea glass enthusiasts don’t like to share where they find their best stuff, but LaMotte has advice for eager newbies.

How to hunt for your own glass

“Anywhere along the Bay on the Eastern Shore from Cape Charles all the way up to Cecil County, Maryland, I think you’re going to find some good pieces there,” LaMotte said. “Using a kayak is always better, because you can get away from the rest of the people who are looking for sea glass.”

LaMotte recently went hunting by kayak on the Eastern Shore of Virginia. She said Calvert and St. Mary’s Counties in southern Maryland are also great places to check out, and added that a friend finds marbles along the Baltimore shore.

“You need to do a little bit of homework, and that might include doing some research on where the small little towns were,” she said.

“… [Where] was the town dump, and also looking at where the tributaries come out into the bays and the oceans because a lot of times that rushing water’s going to deposit the sea glass on the banks. You might find a little bit more.”

You can also visit your chosen beach at low tide when the beach is widest, but kindness is encouraged as collecting sea glass can get competitive. LaMotte’s favorite sea glass find of all time is from Smith Island, Maryland.

“A friend took me to an island that had been deserted in 1920. It had 300 people living on it at one time, but because of the rising waters in the Chesapeake, the last person left in 1920. We got off the boat and I looked around, and the whole beach was filled with shards of sea glass,” LaMotte said.

The glass is from bottles of baking powder that residents used to make bread.

“It was just an eerie feeling of actually being able to connect the 100-plus baking powder lip shards with the fact that all these people that lived here for so long were making bread for all those years,” LaMotte said.