WASHINGTON — “What’s a salamander’s skin like?”

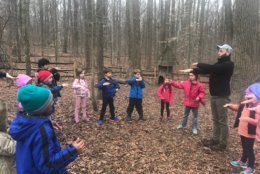

It’s late in the afternoon and Sam Horning is quizzing a group of 6-to 10-year-olds on the day’s science lesson.

Their responses don’t come with the raise of a hand. Instead, the students wiggle their bodies, and after a few seconds of movement, yell, “moist!”

“And why is their skin moist?” Horning asked.

“Because they breathe in it,” a few more answered, while expanding their chests to take a series of exaggerated breaths.

Next, Horning moved on to temperature regulation, which the group aced after making digging gestures toward the ground. It’s safe to say most students don’t learn about amphibians with a choreographed dance. But for students of the Moving Field Guide, that’s exactly what happens.

“Instead of sitting in a classroom and reading a book and taking a test, this gives kids an opportunity to move around and be creative, and to actually create a sequence and a movement in their bodies,” said Alison Waldman, marketing and communications manager for Dance Exchange, a nonprofit arts center in Takoma Park, Maryland, that runs Moving Field Guide.

“And that’s something that kids have a better time remembering (versus) something that they have only just read, and it engages learners of all kinds.”

Dance Exchange Executive Artistic Director Cassie Meador developed the Moving Field Guide program in partnership with the National Forest Service as a way to teach students about ecology and the environment through dance. During weeklong camps and weekend workshops, naturalists lead participants on nature walks that focus on a specific topic — one day may be dedicated to soil, while another is all about rocks and minerals.

Each fact taught along the way gets paired with a specific movement, and at the end of the day, all of the movements from the lesson get put together into a dance.

“So we use the dance as a review, as a synthesis of the information from the naturalists,” said Horning, a resident artist and programs manager at Dance Exchange.

Learning that quartz rocks crack as the earth shifts, for example, is paired with prayer hands that forcefully break apart. Lifting the right arm up past the head helps students remember that amphibians only come out when the temperatures are high.

“It’s amazing. Sometimes they actually are so inspired by what it is that they’re learning that they’re already generating the movement and they don’t know it,” Horning said.

In addition to helping young minds retain new information, Waldman added, “It helps them facilitate a stewardship and appreciation for the world around them.”

Merging science and art to enhance learning is an approach that’s gaining traction — or STEAM (an acronym for science, technology, engineering, art and math) — in the field of education. A study published in the journal Economic Development Quarterly found that college graduates who majored in STEM fields and went on to own businesses or patents had more childhood exposure to the arts than most Americans.

Many schools in the country integrate arts into math and science curricula, including The Lab School of Washington, in Northwest D.C., and Wiley H. Bates Middle School in Annapolis. The Rhode Island School of Design even houses an initiative that aims to put art and design at the center of scientific innovation.

“It’s a great way to help them remember and I think connect ideas that sometimes might not feel like they actually connect,” Horning said.

Dance Exchange has four Moving Field Guide camps planned for summer 2018 at Brookside Nature Center and three planned for its Takoma Park location. Details and information on registration are available on the Dance Exchange website and Active Montgomery.