WASHINGTON — In 1830, it was not uncommon for the average American to consume 7.1 gallons of pure alcohol in one year. In fact, it was the norm.

And perhaps it’s one reason why 50 years later, it became illegal to manufacture and distribute alcohol in the United States.

It’s no bartender’s secret that throughout history, America has had a rocky relationship with alcohol. Now, you can stumble through that history at the National Archives’ latest exhibit, “Spirited Republic.”

“When we’re telling the story of America and we’re telling the story of drinking, they’re both intertwined,” says Derek Brown, mixologist and owner of Mockingbird Hill, Eat the Rich and Southern Efficiency in D.C.’s Shaw neighborhood.

Brown, a 2015 James Beard Awards semifinalist, was tapped by the museum to serve as the exhibit’s Chief Spirits Advisor. “It’s really seeing the lens of our own experience with alcohol and how we created and formed this republic,” he says.

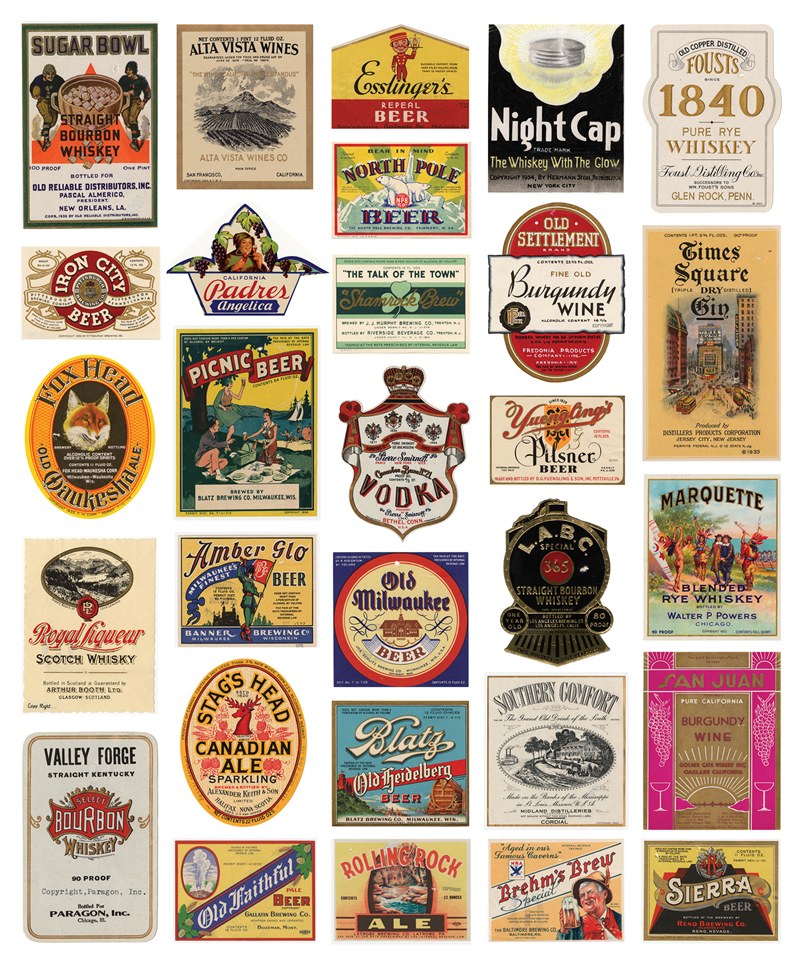

The exhibit showcases more than 100 documents and artifacts that tell the tale of alcohol in America — from a replication of George Washington’s pot still, to the Volstead Act, to Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s cocktail shaker.

It also highlights the birth of the cocktail and chronicles its growth.

“It’s interesting to see, on one hand, drinking starts to become a little more of a concern for Americans, but cocktails become popular. And we see the birth of the Golden Age of cocktails,” Brown says.

“I think one of the coolest and most interesting parts of it is how the cocktail becomes a very individualized drink. … And to me, that’s a little bit of sociology there. You start to see that the American idea is much more democratic, much more independent, much more individualized.”

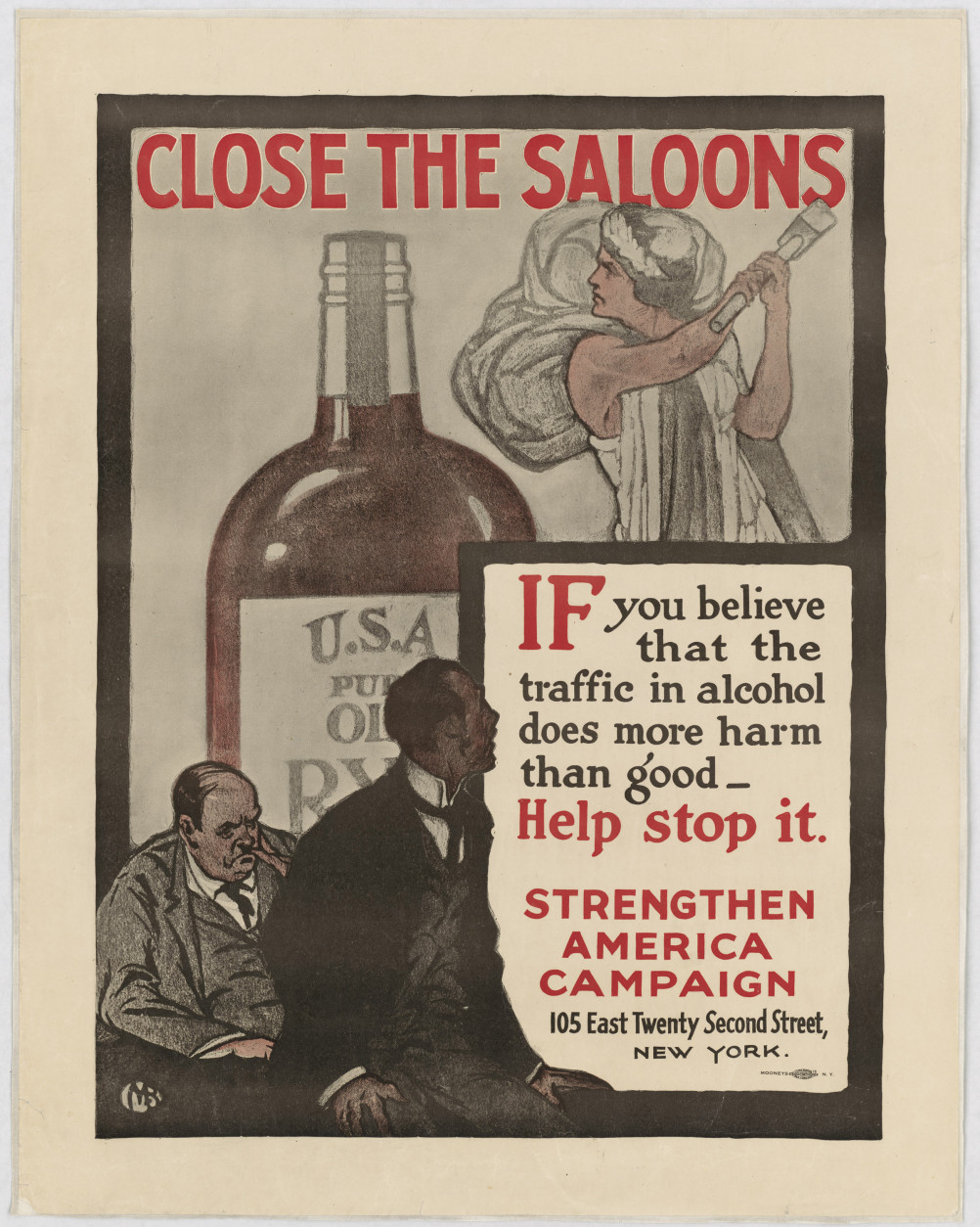

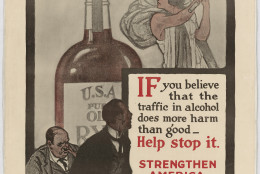

When alcohol rations were banned from sailors in the U.S. Navy in 1862, many Americans’ attitudes toward alcohol began to change. This shift in ideals, in combination with a flurry of unresolved political issues, led to a historic ruling. It was the perfect storm that passed prohibition, Brown says.

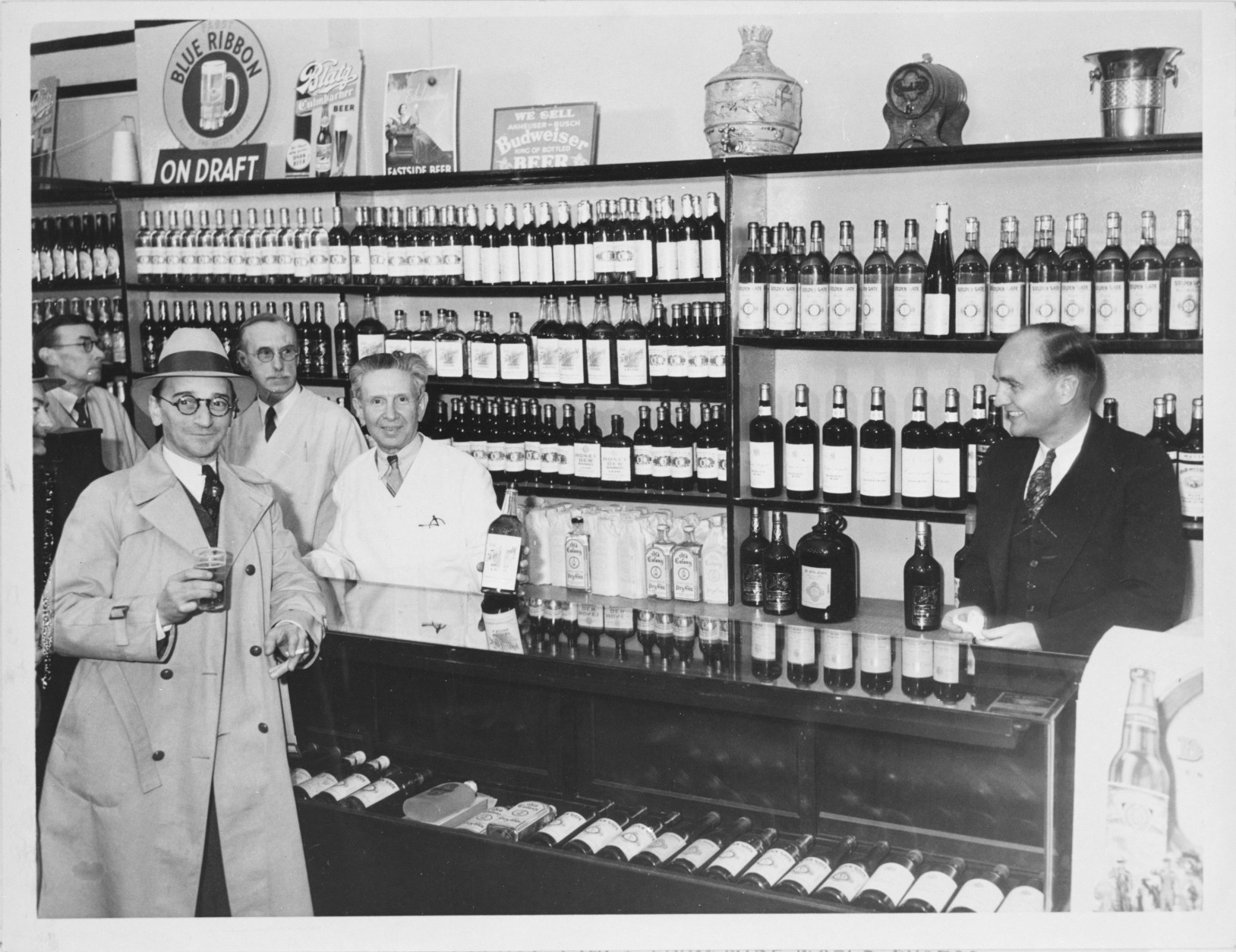

Ironically enough, prohibition didn’t lead to a decline in drinking — especially in Washington.

“We weren’t dry at all,” Brown says. “In Washington, D.C., there was no need of such a thing; it turns out that [drinking alcohol] was an open secret.”

Those outside of Washington drank as well.

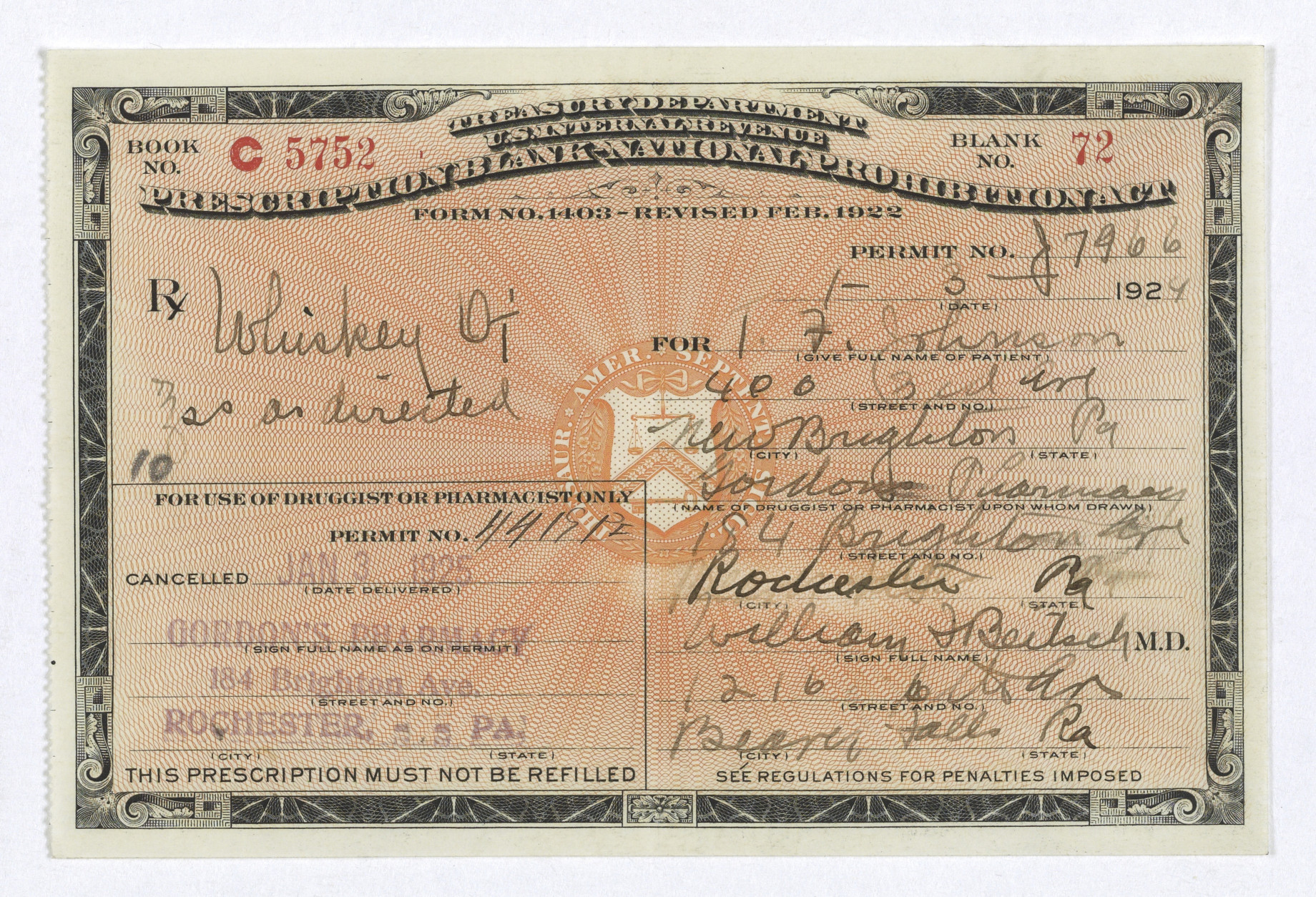

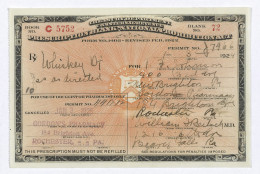

“We became a nation of scofflaws,” says Brown, referencing the exhibit’s documents for whiskey prescriptions and home brewing kits.

When prohibition came to a close, it opened a whole new era for alcohol in America. Bartending became more elaborate, mixing cocktails at home became more popular and the country saw an increase in beer and spirits producers.

Brown says sherry, rye whiskey and rum were reinstated as American favorites, and in 1940, vodka grew in popularity.

The exhibit also taps into the country’s growing awareness of alcohol’s effect on public health — especially when it comes to drunken driving. It includes the first drinking and driving public service announcements, as well as the founding documents for Alcoholics Anonymous.

The exhibit, however, is not limited to the gallery walls. “Spirited Republic” also includes a series of 10 seminars on the history of the cocktails, starting with B.C. (before cocktail), leading up to the current “platinum age” of the cocktail.

The series, curated by Brown, brings together some of the most respected history and beverage experts; it begins Saturday, May 16 and runs through Dec. 12.

If you prefer to get a firsthand taste of the exhibit, you can do that too with “Spirited Republic’s” Bar Trail. With each seminar in the series, two of 20 partnering bars will showcase a drink that ties to the specific moment in history.

To coincide with the May 16 seminar, Mockingbird Hill and Tryst are pouring cocktails to represent a time before the cocktail was even born.

“They’re doing incredible cocktails that involve chocolate and cider and some of the old ingredients that were here, even before the republic existed. … You can just go drink history,” Brown says.

“That’s an important thing about this exhibit: to realize that drinking is so connected to our culture, and to our political processes.”

Derek Brown on the history of the American cocktail: