Almost two months into the congressional impeachment inquiry of President Donald Trump — which began with news of a controversial phone call to Ukraine President Volodymyr Zelenskiy — the public is still a bit fuzzy about the way a presidential phone call with a foreign head of state works.

The somewhat complex process of setting up, monitoring and memorializing such calls has been overshadowed by the partisan name calling, finger pointing and general political disarray in D.C.

And for those who investigate the process, the standard procedure of a call may come as a surprise.

First of all, presidential phone calls are not recorded. And exact word-for-word transcripts of them don’t exist, either.

Written accounts of presidential phone calls have been standard practice for decades, and contrary to popular belief, no presidential phone call has been recorded in more than 40 years, since Richard Nixon’s days in office.

Franklin Roosevelt and Nixon are the only U.S. presidents in history to record their official phone calls. Roosevelt did it for a brief time in 1940. Nixon, from 1971 to 1973, recorded not only his conversations with other administration officials, but also calls with family members, and White House staff were taped, as well.

It was the existence of such tapes — and Nixon’s refusal to comply with a congressional subpoena to turn them over — that led to his impeachment and ultimate resignation.

Since then, a process called a “memorandum of a telephone conversation” (or “Memcon”) has been used to document presidential phone calls.

But these written accounts are not actual transcripts either. They are composite representations taken from several people who listen in on the calls.

Organizing a presidential phone call

When someone decides that the president needs to talk to a foreign head of state, the White House Situation Room is contacted.

“The national security adviser, one of his deputies and the chief of staff will come to the director of the Situation Room and advise [them] the president needs to make a call to foreign leader X,” said Laurence Pfeiffer, former director of the White House Situation Room during the Obama administration.

The Situation Room, according to Pfeiffer, “then reaches out to that foreign leader’s staff and settles on a date time for the call. They test the phone lines to make sure the calls are clear. If there’s any issues, we try to resolve them on both sides so that the president will have a good clear communication.”

“On the day of the call, the Situation Room director goes to the Oval Office,” Pfeiffer said. There, “he would join the national security adviser, one of his deputies, perhaps maybe the White House chief of staff, and usually a senior director of the [National Security Council] who is responsible for the area of the world that that leader’s from.”

Several members from the senior director’s staff are there to help prepare the president for the call.

According to Pfeiffer, “They would review talking points that the president probably got ahead of time, maybe overnight,” and “they would do a walk-through of the call with the president.”

The objective is to make sure the president understands the goals of the call and, Pfeiffer said, “what needed to be said [and] what shouldn’t be said.”

During that process, the Situation Room is setting up the call.

“The director of the Situation Room is on the phone at the end of the couch in the Oval Office talking to the Situation Room. And as the president wraps up his prep, he’ll usually give me the ‘hi’ sign,” Pfeiffer said.

The Situation Room director, according to Pfeiffer, “then lets the Situation Room know, and they will tell the foreign side to bring the foreign head of state to the call.”

The Situation Room director, at that point, will cue “the president to pick up the handset on his desk and then phone call begins,” Pfeiffer said.

Documenting a presidential call

The Situation Room’s role does not end there.

“The Situation Room, at that point, continues to monitor the call, make sure it stays good quality. In addition, they develop the initial rough transcript of the call,” Pfeiffer said.

That transcript is produced, in part, usually by two to three of the duty officers on the watch at the time.

Pfeiffer and other former White House National Security Council staffers whom WTOP spoke to said the document is produced this way: The duty officers all have headphones on. Two of them are rapidly typing every syllable and utterance they hear, as best they can. The third person is using a slightly different practice: They have a headset on with a microphone.

According to Pfeiffer, that third duty officer is “in a quiet room somewhere, and they are repeating into the microphone everything that you hear the president and the foreign leaders say, a word-for-word. That duty officer’s voice goes into a computer, and a transcript of the duty officer’s voice is created, replicating the call.

“No actual voice recording of the president or the head of state is made,” he said.

In fact, in a somewhat counterintuitive step, the duty officer’s voice is not recorded, either — at least in an audio sense.

The voice is just transcribed, using a speech-to-text process.

At that point, Pfeiffer said, “the duty officers then bring together their three versions of the transcripts and they reconcile them to one. Odds are, somebody heard something slightly different than somebody else — you know, the name [of] a project, or a country name. They reconcile all that.”

The path of a transcript

After a transcript is produced, it is provided to the directorate of the National Security Council responsible for the call.

“They’ll finalize that transcript and that could be anything from a detailed line by line transcript like we saw on the Ukrainian call, or it could also be a written prose summary of the call, or it could be a very short two or three sentence wrap-up of the call, said Pfeiffer.

That then becomes the memorandum of the phone conversation. It is then sent to the national security adviser’s office, where staff reviews the transcript.

Pfeiffer said changes in the transcript text are possible, but unlikely. “Odds are they probably won’t make any changes,” he said.

“A distribution path for the Memcon is then decided upon,” Pfeiffer added. That path “might include the secretary of state, secretary of defense, maybe the director of national intelligence, the director of CIA.”

The memo is then sent to the National Security Council’s executive secretary. Pfeiffer playfully remarked: “You know, we’re a government bureaucracy. All bureaucracies usually have an executive secretary that moves paper.”

Copies of the transcript are shared with all necessary parties inside and outside of the White House, who, according to Pfeiffer, “have the discretion to share the transcript with individuals within their department or agency who worked the particular issues so that they are cognizant of what transpired on the call.”

Even though less than a half dozen White House officials may actually listen to a presidential phone call, Pfeiffer said, many times that number may actually view or handle the transcript.

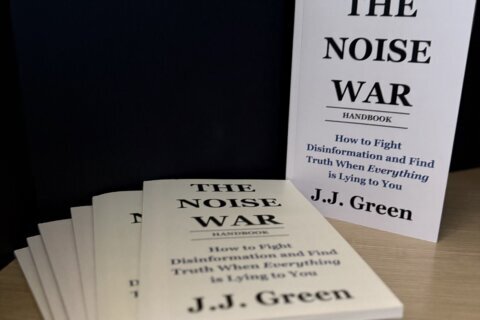

You can hear more details about how a presidential phone call is set up and documented on Episode 195 of the Target USA Podcast.