This article is part of the WTOP series, “Facing Down Fentanyl: Teens Confront Drug Danger.”

This video is no longer available.

Getting someone with a substance-use disorder into a recovery program is a difficult process, even if that person wants help — in part because the list of those programs is a short one. The process is made even more difficult for parents with teenagers as this list is even shorter.

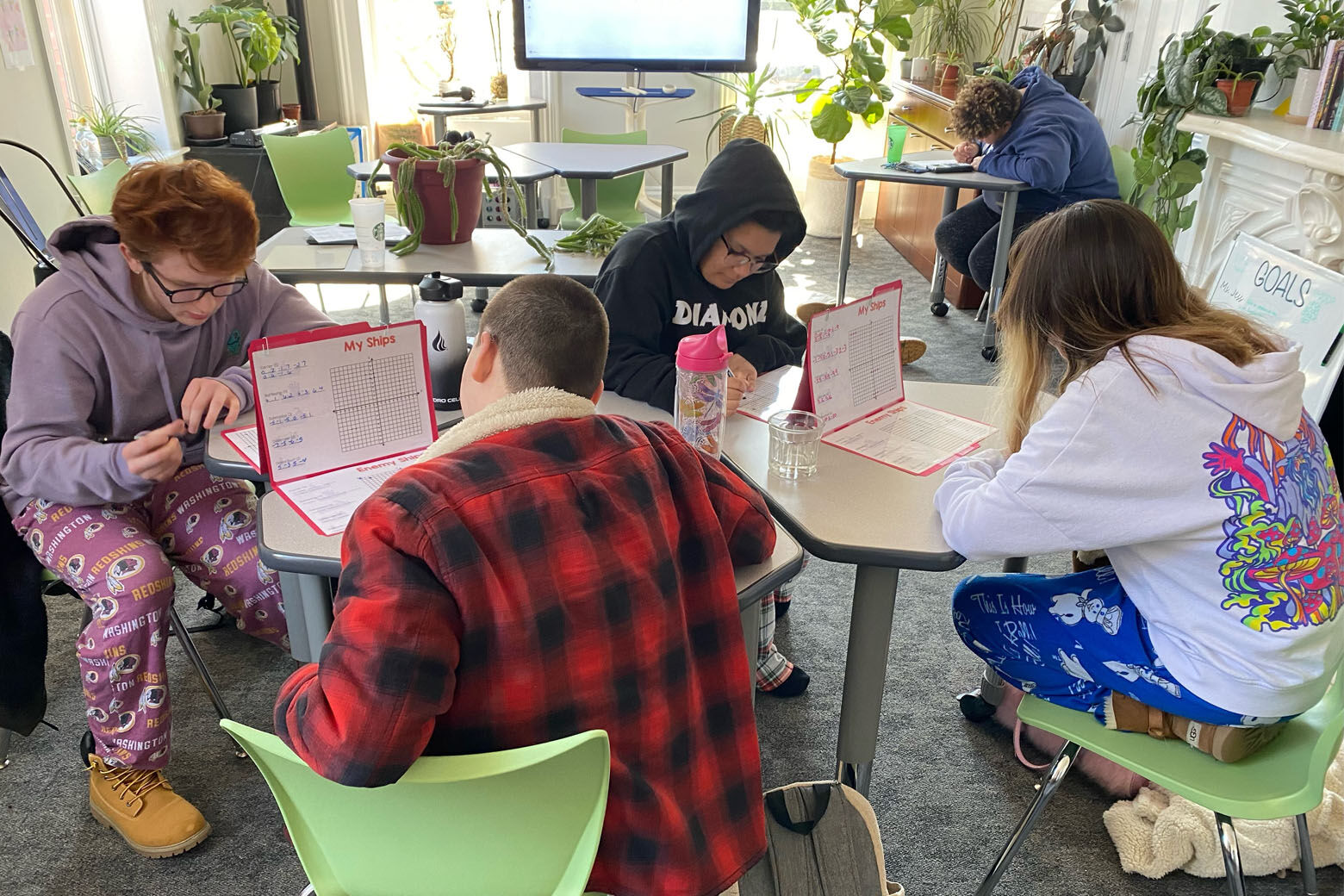

In the City of Frederick, Maryland, an alternative high school helps students battling addiction.

“A lot of these kids that come to us … for so long feel, you know, unseen, unheard, invalidated and not supported,” said Jessica Nicholson, the community relations director at Phoenix Recovery Academy.

The academy offers teens between the ages of 14 and 18 a place to not only continue learning but also provide the tools and support students need to recover from their addiction.

The school is fully accredited through the Maryland State Department of Education, Nicholson said. Some students come from as far away as Anne Arundel County to attend class and continue their journey to sobriety.

“We really try to create and cultivate that environment of they’re not alone, right, and they have that direct support,” Nicholson said.

Nicholson knows well the struggle facing the children who enter the school. She began using drugs at a young age herself, before hitting rock bottom and turning her life around. She now shares her personal battle with students to show them getting sober is possible.

Holding each other accountable

Nicholson said providing students support is an important part of the school’s process.

For students in the school, they find strength not only from the staff, according to Nicholson, but also their fellow students.

“They’re really great about holding each other accountable and showing up for one another … It’s pretty powerful,” Nicholson said.

Recovery plans are developed for students and staff members to help make sure they stay on track. In addition to drug testing, the school also has a points system, which rewards positive behavior, such as getting enough sleep, taking medications and showing up to support groups. Those points can be cashed in on things such as trips the academy does each month.

Read more from the series “Facing Down Fentanyl: Teens Confront Drug Danger”

- The small blue pills behind a surge in children’s fentanyl-related hospital visits in the DC area

- ‘Not my child:’ What a mother says you need to know about teens and fentanyl

- Md. school system races to battle fentanyl epidemic facing teens

The goal is to show students “the perks of sobriety,” Nicholson said, “and teaching them how to, like, genuinely live life,” Nicholson said.

The school fills an important need in the state, which only has a handful of similar programs and only one residential program, Sandstone Care, in Crownsville, Maryland, for students battling addiction. Nicholson said the academy would like to offer residential programs down the road.

The state needs more resources for residential treatment, Nicholson said. “We need to have more outpatient resources. There are some places … throughout the state that have nothing,” she said.

Sharing her story

Nicholson is a staff member who serves as an inspiration to students at the school. She said she developed a drug addiction while she was a teenager.

Nicholson said the roots of her addiction stretch back even further. She said she struggled with mental health issues at a young age and also experienced trauma, including abuse.

Her addiction began with abusing prescription drugs, which she could get because of autoimmune conditions she has that progressed as she got older.

It started with snorting pills. Then injecting. “To then ultimately turning to heroin,” Nicholson said.

During her struggle with addiction, Nicholson looks back and said there are several instances where it could have ended her life.

“I totaled my car. I was cut out of my car. I was found, you know, blacked out and passed out multiple times,” Nicholson said.

Nicholson went in and out of recovery. With addiction, you commonly hear people say you have got to hit rock bottom. That only comes when a person decides to “stop digging,” she said.

For Nicholson, her turning point was when a dealer made threats against her family, including her then seven-year-old daughter.

“I think that was a moment where it all just kind of hit me. You know, I finally put my hands up and surrendered,” she said. “To know that my own selfish actions were, you know, potentially putting those around me that I love and care about in harm’s way was just too much.”

As she marks eight years sober, she said, life can challenge her sobriety because that “cushion” or “relief” which was at one time drugs, is no longer there.

“Life still happens. You don’t get sober and it’s all sunshine and rainbows. You know, life still shows up,” she said.

Nicholson said throughout her struggles, her family never gave up on her, and without them, she said she wouldn’t be here today eight years sober.

“I just had a family that kept trying to intervene and love me through it all, no matter what,” Nicholson said.

Addiction is a ‘family disease’

This video is no longer available.

She shares her story with the kids at the academy including parents. While some kids don’t have support at home, others do. But for parents to support their child is sometimes difficult to figure out.

The school’s program includes family therapy. Addiction is a “family disease,” Nicholson pointed out.

When families sit down and try to have conversations, “I think a lot of times, unintentionally … everybody gets aggressive, everybody gets frustrated and hurt,” she said.

The family sessions work to get families to communicate better and help parents figure out how best they can support their children.

She encourages families to put a focus on recovery and not give up on their loved ones, even if they don’t seem interested in getting help for themselves. At the school, she has seen the success stories play out for kids who at first were reluctant to get help.

“Even if I have a shred of willingness … at least some desire to do something a little bit different, and give it a chance, I can work with that,” Nicholson said.