A D.C. hospital is among a handful around the nation involved in clinical trials on a next generation of pacemaker used to control heart rhythm.

“The leadless pacemaker technology is a very substantial leap forward,” said Dr. Zayd Eldadah director of cardiac electrophysiology at MedStar Health.

“In many respects, it’s like the transition from a rotary dial landline to a smartphone. It’s that significant because of the communication piece, the miniaturization piece, the convenience piece, the capability piece. So, it’s a big deal,” he said.

Eldadah implanted the first Aveir Dual-Chamber Leadless Pacemaker in the area last July at MedStar Washington Hospital Center.

The device involves no wires inserted into the different chambers of the heart; also, there’s no disc inserted under the skin of the chest to act as a brain center for the readings collected from each chamber.

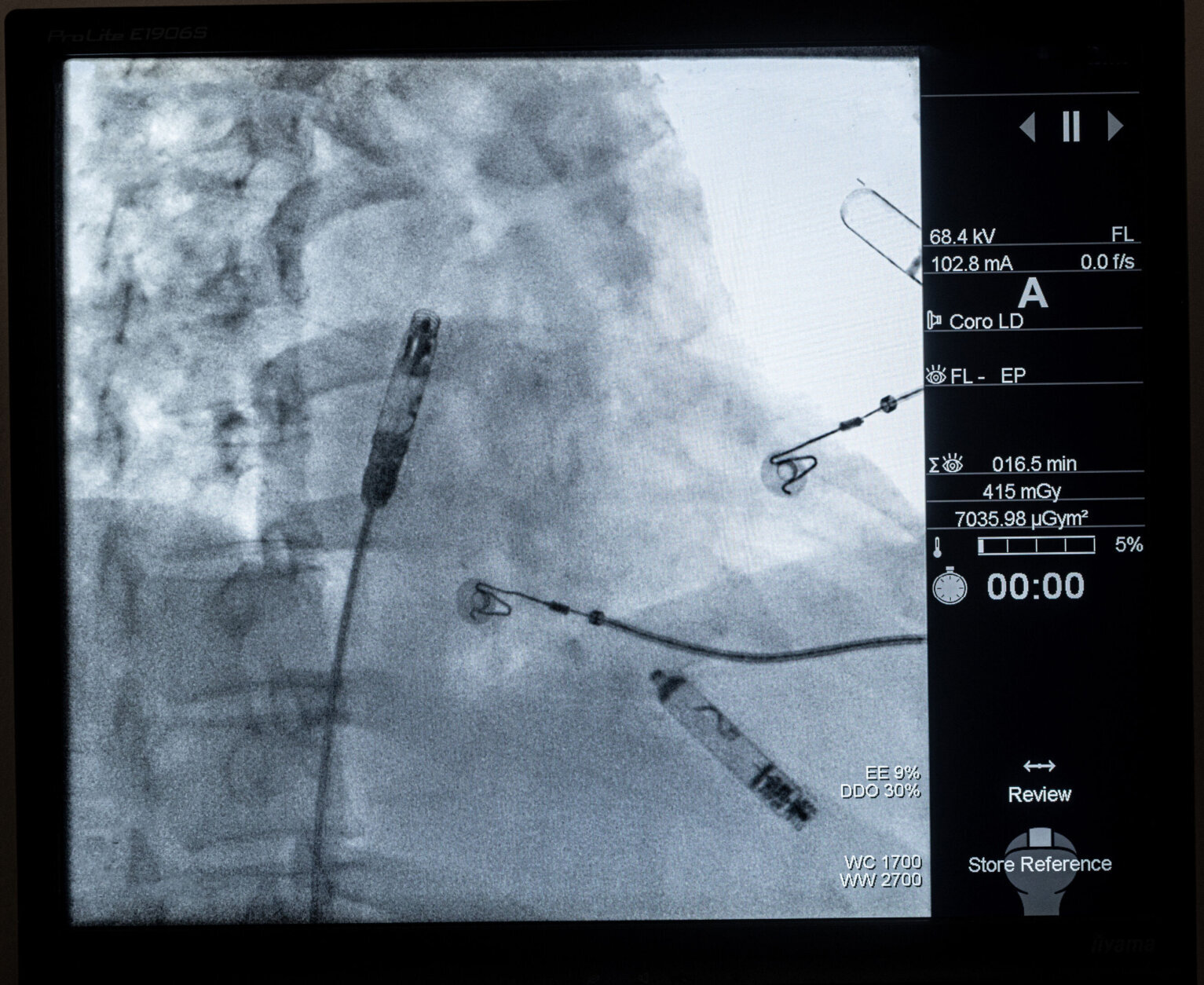

The features that monitor heart rhythm between chambers and deliver energy to adjust the pacing have been miniaturized into two capsules, which are inserted within the heart using the device system’s catheter that is fed through the thigh.

“The real technology advance is having those two capsules communicate by delivering energy (electrical signals) through the bloodstream itself to get perfectly timed pacemaker signals,” Eldadah said. “Because if you don’t have information that is correct, you can imagine you’ll have two independently running heart chambers, which will be completely out of sync.”

Eldadah said recovery time for patients receiving the leadless pacemaker involves a few hours of observation to make sure there is no bleeding from the incision site on the thigh.

“The patient goes home, and they recover a little bit from the anesthesia that afternoon. But by the next day, they’ve completely resumed their normal lives,” he said.

Conversely, recovery time for someone receiving a traditional pacemaker might be three to four weeks — for the skin to heal and any bleeding to resolve. And, the left arm where the pacemaker is placed has to stay relatively immobile, so the wires that were implanted don’t get yanked out of place.

If the study goes well, the device could become universally available.

“We hope very soon. And we think it’s going to change people’s lives for the better,” Eldadah said. “It’s a big step forward in the ability to treat heart rhythm disorders.”

“We hope it will be yet another step along the way that is well underway of many technologic advancements that have happened over the past 10 to 20 years, and we hope will even accelerate in the next 10 to 20 years to make people live longer and live better, with less invasiveness and less risk.”