Impending snowstorms, such as the one headed for the East Coast, create extra anxiety for families living with someone prone to wandering.

Wandering is a matter of life or death when someone with Alzheimer’s disease or dementia goes missing. Virginia State Police issued 43 senior alerts last year, and four of the people were found dead; of the five silver alerts issued by Maryland State Police this year, only three had been located, as of this week.

For some people wandering can be aimless with no destination.

“In my dad’s situation … it was never aimless,” Jennifer Van Oss said. “He was very productive, very work oriented. And so he tried to go to work all the time. All hours of the day and night, he thought he needed to be in the office.”

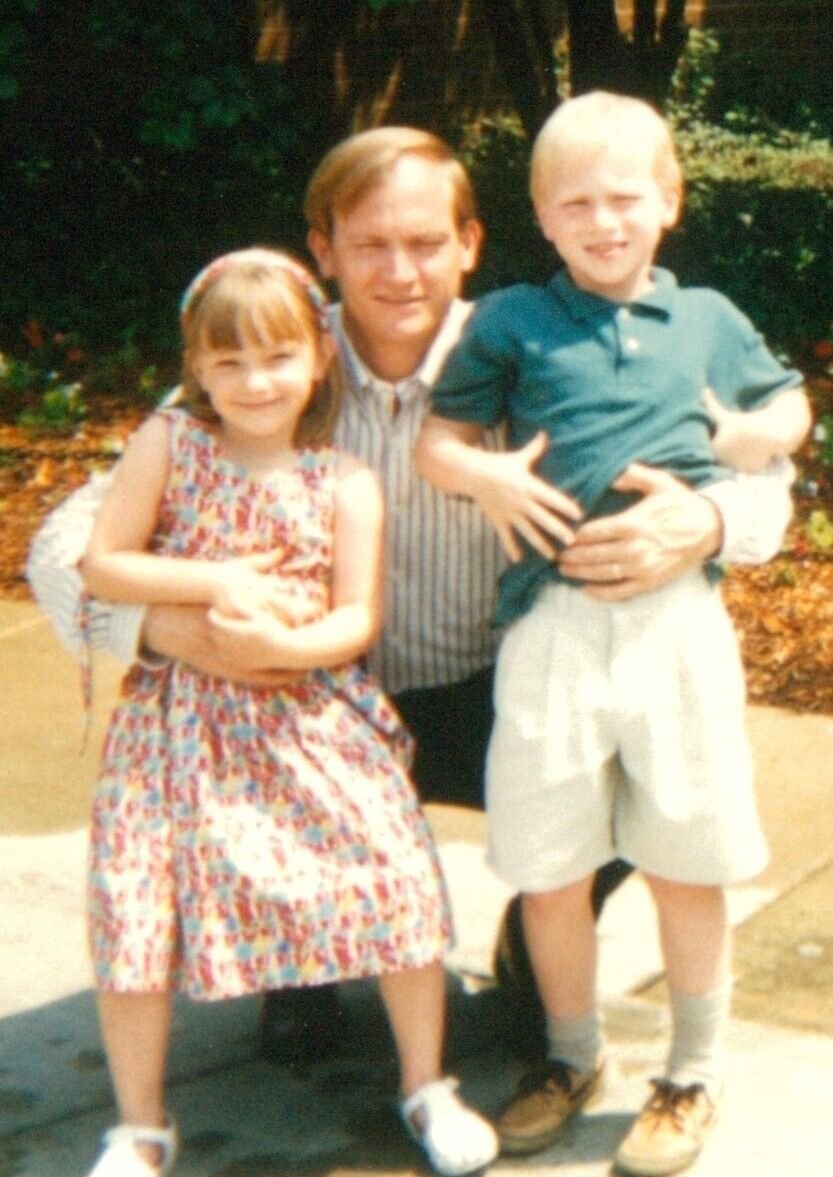

Van Oss, of Northwest D.C., was 15 years old when her father was diagnosed with younger-onset Alzheimer’s disease at 52.

As a sophomore in high school, while her brother was a senior, they began taking turns with their mother keeping vigil around the clock.

“It’s all very fresh still; it was about 10 years ago now. But it stays with you. A lot of that really shaped who I am as a person,” she said.

Two incidents of her father wandering stick in Van Oss’s mind. The first was a red flag that he shouldn’t be allowed to drive anymore when he got lost driving to work. The second involved Van Oss and her mother randomly driving by her dad who was walking down the street. “But, had we not taken that route, we may not have seen him and we may not have found him,” she said.

That’s when the family resolved to never to leave him alone — ever.

“My mom, my brother and I ended up very drastically altering our lifestyle at home to make sure that somebody could be with him at all times. But it wasn’t just the three of us, we utilized our neighborhood network, my dad’s work network, and our friends at school, actually,” she said.

There is stigma surrounding dementia and Alzheimer’s disease, and Van Oss encourages people to be honest with others and to build a network for help and support.

For about a year before her father went to an assisted living facility, Van Oss said she and her brother essentially had friends over all the time to be extra sets of eyes on him, to engage with him or provide activities, such as distractions when he seemed prone to roam.

“Something that we would frequently do to kind of redirect him was we would find other things around the house that he genuinely could help with. Even though his skills were limited at that point, we would find tasks for him to do that would make him feel useful, and were useful and were helpful,” she said.

She said that made both of them happy.

“Because there are always ways that people can be helpful and can contribute. And it was so important to us to preserve what we could of my dad’s dignity because Alzheimer’s really strips a person from their dignity,” Van Oss said.

People in the neighborhood also knew to look out for him.

“So we had sets of eyes on him pretty much everywhere he might go. And, that was just enormously helpful. And we needed it because there were several times where people actually did call us and kind of raise the flag, and we could act quickly enough to avoid a catastrophe,” Van Oss said.

Van Oss said 90% of her family’s life during those couple of years seemed extremely abnormal.

“I felt like nobody could possibly relate to me as a 15-year-old who is dealing with this. But the people that I surrounded myself with made me feel very normal, it was a breath of fresh air,” she said. “I don’t know who it was that said it, but somebody said, ‘If you’ve seen one case of Alzheimer’s, you’ve seen one case of Alzheimer’s,’ and that is so true. Everybody deals with it differently. Everybody experiences it differently.”

The Alzheimer’s Association has a 24/7 help line at 800-272-3900.

“You can call 24 hours a day, and you will get a real person who will talk to you and help you. And, you know, sometimes you just need to hear that you’re not the only one dealing with it because it’s such an isolating illness,” Van Oss said.

Van Oss’ father died when he was 55. The challenge of Alzheimer’s disease will be affecting increasingly greater numbers of families.

“The number of Americans living with Alzheimer’s is growing — and growing fast,” said Cindy Schelhorn, with the Alzheimer’s Association. “More than 6 million Americans are living with Alzheimer’s today, a number that’s projected to rise to nearly 13 million by 2050.”

Oss now volunteers with the Alzheimer’s Association and is on the committee for its annual fundraiser called “The Longest Day.” Held on the summer solstice, the day with the most light, its intention is to fight the darkness of Alzheimer’s disease.

“As the world’s largest nonprofit funder of Alzheimer’s disease research, the Alzheimer’s Association is committed to accelerating the global effort to eliminate Alzheimer’s,” Schelhorn said. “We’re working hand in hand with communities across the country to provide information, education and support for all those affected by Alzheimer’s and all other dementia. No one needs to face this disease alone. We’re here to help.”

You can learn common signs that a person may be at risk of wandering and strategies to help cope and reduce the risk on the Alzheimer’s Association website.

You can find advice for reducing the risk of wandering and what to do when an incident happens at alz.org.